Finance is like the circulatory system distributing oxygen and nutrients through the human body, stabilizing its temperature, and so on. It’s prone to strokes. What led to Mr Economy’s massive one in 2007? Will he have more? How severe will they be? And will he ever recover from the paralysis that one caused?

Our economy depends on finance to flow. Unfortunately, Washington has the wrong model. When the flow stopped in 2007 they applied giant plungers, TARP and Quantitative Easing, to what they imagine is a blocked financial toilet. Not surprisingly, the flow has not been restored.

To understand what led to the cerebrovascular accident and what risk factors to change, we must first know the purpose of finance, what it should do, and its basic mechanisms. Its purpose is to help people save, manage, and raise money. What it should do is allocate capital where it will have most value and efficiently reallocate risk. Its mechanisms are securities, credit and insurance.

We need to know how those mechanisms work to understand how and why the circulation of finance got interrupted.

Securities can be bought and sold. Their traditional function is for commercial enterprises to raise new capital from investors who seek income and/or capital gain. Their traditional categories are equity and debt. Equity securities represent fractional ownership of the issuer, debt securities a loan. Debt securities typically require regular interest payments and the issuer must repay the loan. Equity securities are not entitled to payment but may receive a periodic share of the issuer’s profits. Equity owners hope the value of the issuer, and therefore their securities, will increase.

Credit has traditionally been supplied by bank loans governed by an agreement between issuer and borrower. Those loans could not be traded. The issuer received interest payments for the use of their capital and protected against failure to repay with a claim on the borrower’s assets, i.e., collateral.

Insurance transfers the risk of a loss from one entity to another in exchange for a payment. The insured accepts a definite small loss in the form of their payment to the insurer in return for compensation in the uncertain event of a larger financial loss.

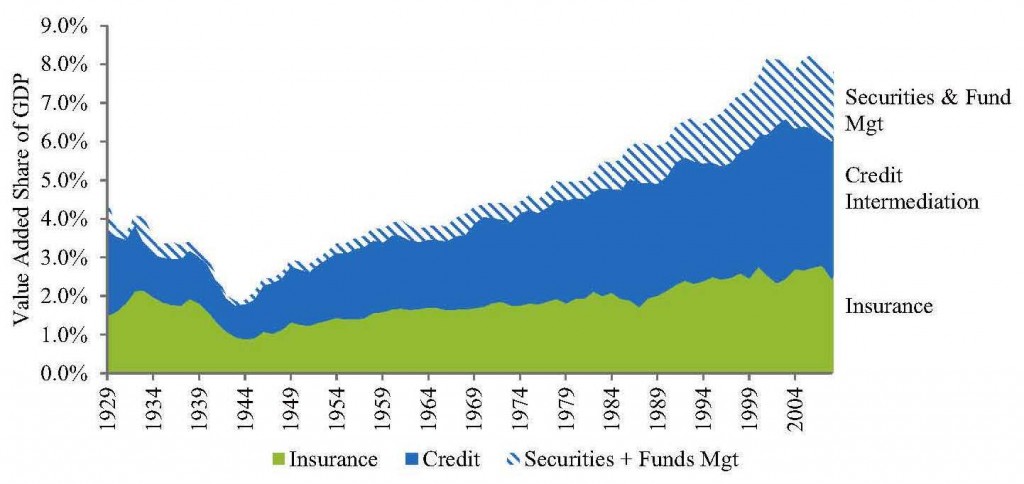

Several things changed in the past three decades. There was a great increase in securitization of what was originally credit. Security, credit and insurance transactions got combined in new and ever more complex ways. Financial regulation was relaxed and funding of regulatory oversight was cut.

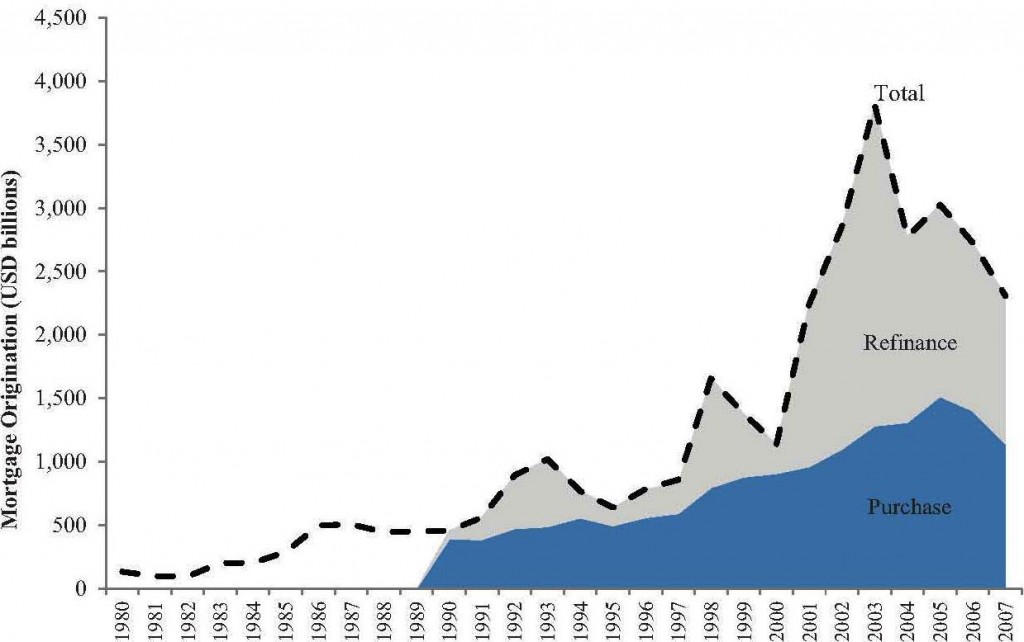

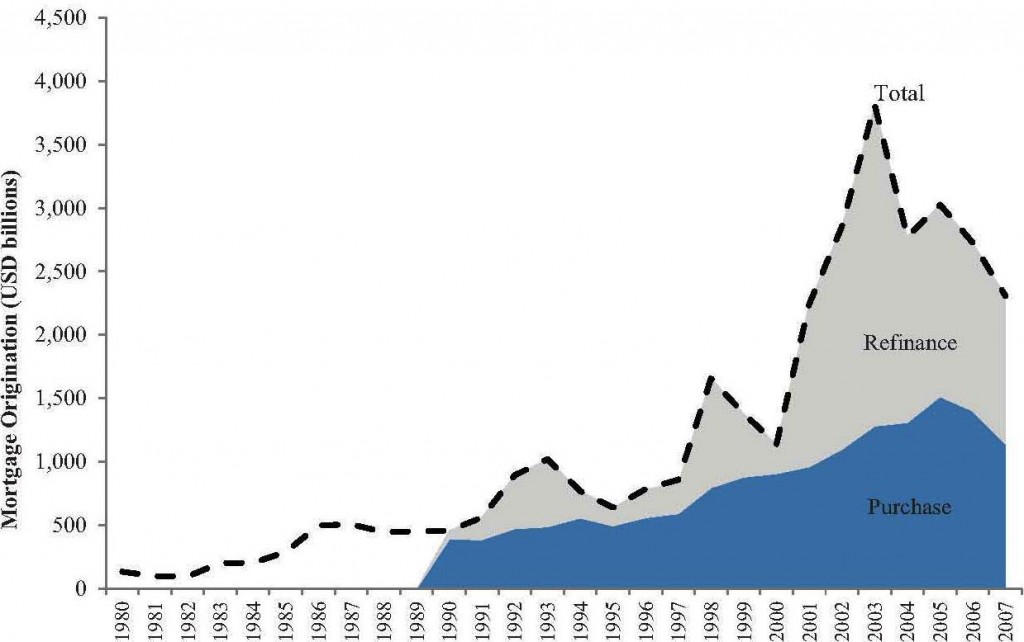

Mortgages (i.e., credit) were bought in bulk, repackaged and resold as new types of securities, CDOs, Collateralized Debt Obligations, Re-REMICs, Re-securitizations of Real Estate Mortgages, ABS, Asset-Backed Securities, MBS, Mortgage-backed Securities and etc. Banks could now originate more mortgages because the ones they sold were no longer on their balance sheet. Buyers of mortgage-backed securities could pay for them with money borrowed against other securities as collateral and hope to resell them for a quick profit. They could insure against their collateral’s possible loss of value. And so on and so on.

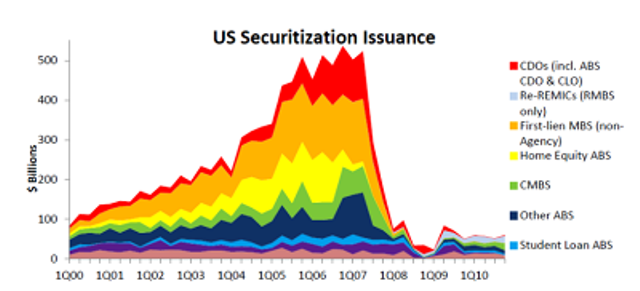

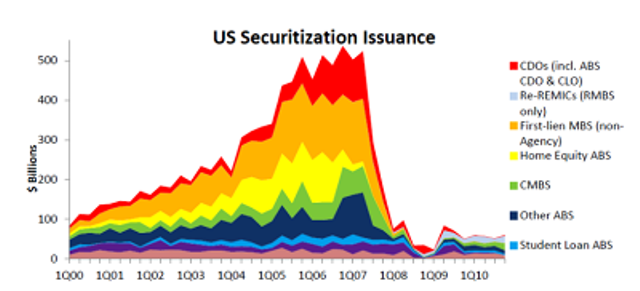

That increased complexity accelerated the financial system’s growth but also made it more fragile, which increased risk for the overall economy. Issuance of these new kinds of derivative securities (chains of transactions derived from an asset) exploded from less than $100B in 2000 to more than $500B in 2007. That’s when the uber-stimulated financial system cratered and Mr Economy had his paralyzing stroke.

Financing , refinancing and securitizing doubled household debt from 48% of GDP in 1980 to 99% in 2007. Most of that increase was in residential mortgages, up from 34% to 79% of GDP.

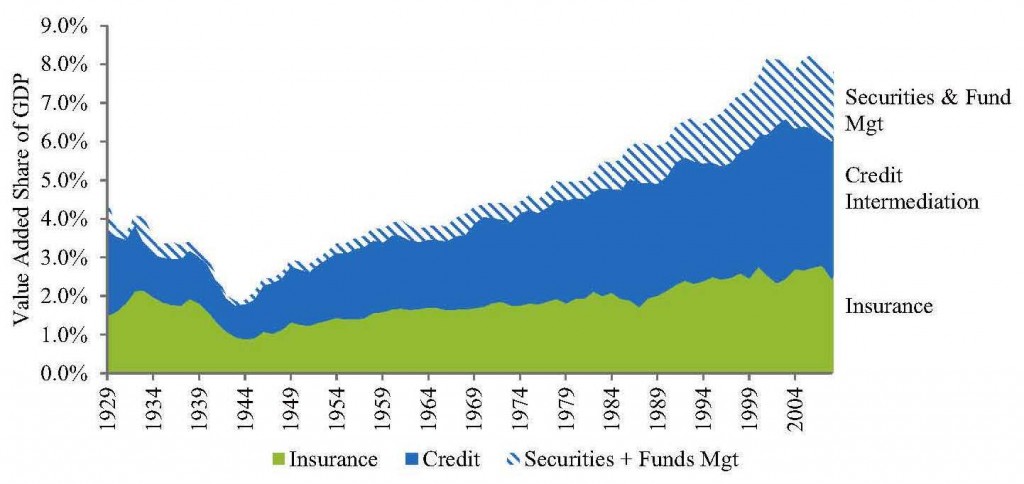

Financial services grew not just from credit intermediation. Management fees grew as people switched from owning individual securities to managed funds, transferred their assets to professional managements, traded more, and as asset values increased. Only 25% of household equity holdings were professionally managed in 1980. That more than doubled to 53% by 2007.

The growth in insurance was mainly in new kinds of insurance associated with securitization.

Earnings of financial services employees grew rapidly along with the financial sector’s growth. In 1980, they typically earned about the same as their counterparts in other industries. By 2006, they earned an average of 70% more.

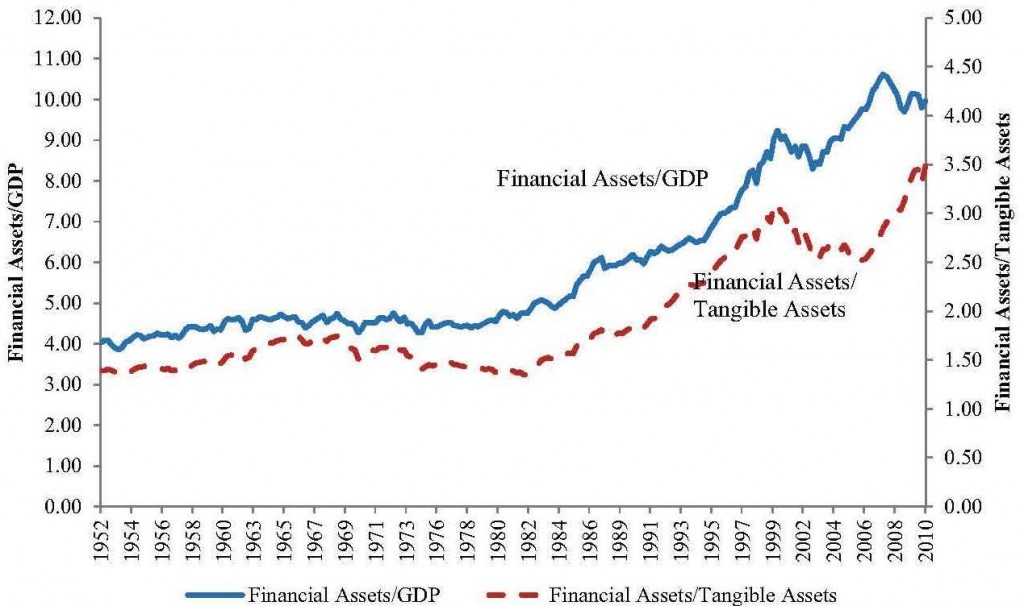

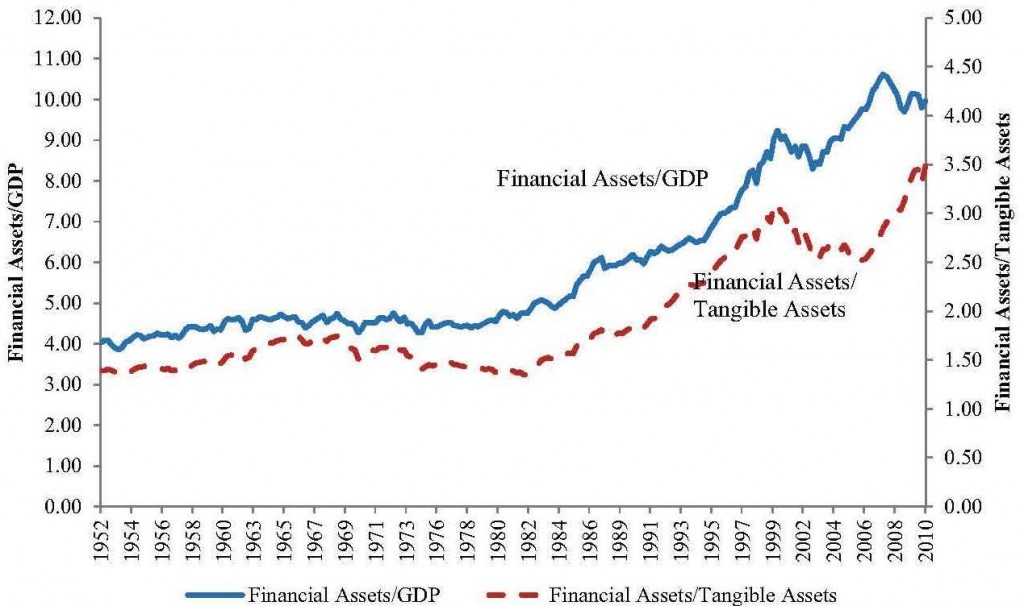

The increase in household debt and associated derivative securities drove the value of total financial assets, stocks, bonds, derivatives, and etc from about five times GDP in 1980 to double by 2007. The ratio of financial assets to tangible assets, e.g. plant and equipment, land, residential structures and etc. grew in the same rapid way. Debt creates money because if you lend me $100 there is now $200, my $100 plus your $100 asset, i.e., my promise to repay. Assuming I do repay.

The increase in household debt and associated derivative securities drove the value of total financial assets, stocks, bonds, derivatives, and etc from about five times GDP in 1980 to double by 2007. The ratio of financial assets to tangible assets, e.g. plant and equipment, land, residential structures and etc. grew in the same rapid way. Debt creates money because if you lend me $100 there is now $200, my $100 plus your $100 asset, i.e., my promise to repay. Assuming I do repay.

Much of the asset growth came from securitization of loans on bank balance sheets, i.e., transforming credit into securities. The total value of debt securities was 57% of GDP in 1980. Securitization of loans added 58% by 2007. The total value of debt securities more than tripled to 182% of GDP.

Much of the growth in equity securities came just from higher equity valuations, i.e., the exuberant willingness of buyers to pay more for potential future gain. The total value of equity securities nearly tripled as a share of GDP between 1980 and 2007, from 50% to 141% of GDP.

Financial institutions traditionally earned spreads on loans on their balance sheets, i.e., they got higher rates of interest on capital they lent than they paid to depositors. That changed with securitization. Now they profited mainly from fee income. By 2007, 61% of home mortgages were in loan pools of mortgage-backed securities, 72% of which were guaranteed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) or one of two Government Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs), Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac.

Securitization of credit was a major part of the development of the “shadow banking” system. Many types of non-bank financial entities now perform some essential functions of traditional banking. Like banks, they use short-term borrowing to issue or buy longer-term securities. Their short term lenders can demand repayment at any time, and they are vulnerable to a drop in the value of longer-term securities, either of which can result in the equivalent of a bank run because deposits at shadow banks are not federally insured.

When financial transactions were primarily between a security issuer and a purchaser, or a bank and a borrower, each party’s risk could be known. When a package of mortgages is securitized, however, third parties buy the securities, insure themselves against severe loss with a fourth party which perhaps insures itself with a fifth party, and so on and so on. It becomes impossible to assess risk for any party. Prudently managed entities can be brought down by others in the chain and if large enough ones fail, the economy of which they are part can collapse. That’s what happened in 2007.

In future posts I will explore, not necessarily in this order:

- What Washington and Wall Street did that made the collapse inevitable

- Why Washington bailed out Wall Street’s largest enterprises instead of allowing them to fail

- Why some Wall Street enterprises were fined for criminal behavior but no executives were jailed

- What must be done so the financial system will fulfill its purpose

We will, I’m sorry to say, come to see that our financial system that should function as a circulatory system is instead being operated as a Washington/Wall Street mine and we are being poisoned by its toxic waste. By exploring how that happened we’ll identify essential changes so the system will instead do what it should. Now, where did I put my hard-hat, flashlight and canary?