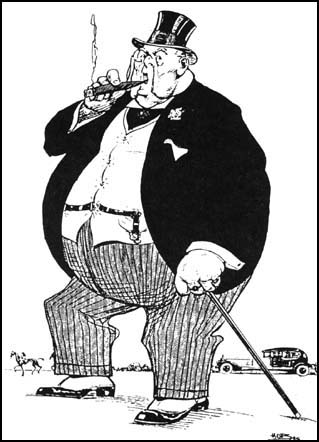

Our finance system stopped allocating capital where it will have most value and efficiently reallocating risk. Previous posts showed how deregulation and bailouts introduced moral hazard, how leaders of big financial institutions responded, and how in 2007 it all blew up. But why did Washington allow the moral hazard to develop and respond as they did to the result? Was there a cabal of corrupt Mr. Moolas?

Probably not. The protagonists seem genuinely to have believed markets would regulate the behavior of their participants. When it went wrong, they did not consider it self-interested to preserve the big financial institutions they understood to be the financial system.

How we conceptualize the world is shaped by our experience. It’s instructive to explore the experience of those whose beliefs got us so far off course but future Fed Chairpersons and Treasury Secretaries will also have conceptual blinders. To avert repeating the catastrophe we must make structural changes.

In this post we considered Alan Greenspan’s expansion of the Fed’s mission to include managing asset prices. His successor, Ben Bernanke, holds the same belief. Central banks do influence asset prices while raising and lowering interest rates to help manage inflation and unemployment but they overestimate monetary policy hoping it can compensate for poorly managed fiscal policy, i.e., government revenue and spending.

What set the beliefs of Treasury Secretaries? Robert Rubin, 1995-1999, had worked at Goldman Sachs for 26 years and was co-chairman from 1990 to 1992. He later became a director of Citigroup and was its chairman at the height of the 2007 crisis. Larry Summers, 1999-2001, formerly Rubin’s deputy, followed his lead against regulating derivatives and for deregulating big banks. Paul O’Neill, 2001-2002, formerly CEO of Alcoa, deplored Bush’s tax cuts, investigated al-Qaeda funding by American allies, objected to the invasion of Iraq, and was fired. John Snow, 2003-2006, formerly CEO of CSX, had to resign when it was revealed he failed to pay income taxes on $24M at CSX . Henry Paulson, 2006-2009, was formerly chairman and CEO of Goldman Sachs. Tim Geithner, 2009-2013, was at Treasury from 1998–2001 under Rubin and Summers, then President of the NY Fed.

With the exception of O’Neill and Snow who had little impact, the beliefs of all these men were shaped by Goldman Sachs. Did they act always in what they believed to be the best interests of all the people? Let’s assume they did. What they believed would have led them to the actions they took. Of course they believed big financial institutions must be saved, and of course they believed it essential to bail them out.

They may well have been right. Deregulation probably had made the big financial institutions too big to fail and bailouts had become Washington’s Pavlovian response to confidence-threatening failure of big enterprises.

But what about after the bailouts? We already considered moral hazard created by bailouts that protect fools from the disasters they create. What about moral hazard created after the bailouts by weak punishment of those who committed fraud? This is where more folks think they see Mr. Moola.

Financial institutions have agreed to settlements that sound large. Global banks agreed to pay almost $11B in the US last year. This January, Bank of America reached a $10.3B settlement with Fannie Mae. The Fed and Treasury reached a separate $8.5B settlement with 10 banks, including BofA. But no institution or executives have been brought to trial. And while $11 + 10.3 + 8.5 = $30B of settlements is a big number, financial sector stocks in the S&P 500 earned $168B in profits last year, up 21% from 2011. The cost of the settlements was inconsequential, $30B of what would have been $200B.

The settlements make even less difference to those responsible. Angelo Mozilo, for example, was paid almost $470M as CEO of Countrywide Financial but paid none of BoA’s settlement for what Countrywide did under his leadership. He did settle with the SEC on unrelated insider trading charges but even there he paid only $47M of the $67M settlement because he had a $20 million indemnification in his employment contract. Criminal convictions have discouraged insider trading. Mortgage and other financial frauds should also have been vigorously prosecuted.

But far more important than punishment for crimes past are major changes we must make (1) to minimize moral hazard and the likelihood of another financial crisis, and (2) so the financial system will allocate capital where it has the highest value. The first, which I will itemize in the next post, are easy to see now that I understand the problem. The second requires more exploration.

It was only after I’d chosen its title and was copy-editing this post that I discovered Nomi Prins, formerly a managing director at Goldman Sachs, had in December 2010 published what sounds like an excellent book on this subject using the same title:

http://www.amazon.com/Takes-Pillage-Deceit-Untold-Trillions/dp/0470928557

I would read Nomi’s book if I wanted to know more about “how the revolving door between Wall Street and Washington enabled and encouraged the disastrous behavior of large investment banks”. Maybe I will, anyway, because it also contains “a savvy and well-developed proposal for extracting ourselves from this downward financial spiral and stabilizing the economy”.

But first I will post the solutions that already seem obvious because I want to move on from risk reallocation to capital allocation. We need to correct our financial system but even more important, we need to correct our economy, refit it for 21st century realities.

Many of your readers have made some good potins. My thoughts are that big banks failed because the top brass were smart in the street sense. The brass was comprised of people motivated by money and pretty much only money. Therefore, they engaged as much profit taking as possible and focused on filling their individual coffers. They were smart, because they ended up rich and that was the only incentive offered to them. They knew the calculus: take all you can and extend the bank as far as possible. The demands for profit were driven by the market, so it did not behoove a manager to play to banking ideals of conservatism. The key was to give the market what it wanted and to earn as much as possible. Let the chips fall where they may. Who needs job security once your net worth is past $10 million? Our society has devolved into nothing but a trading market and immigrant servicing center. There is nothing left to hold us together as one peoples. There have always been greedy people, but today’s world makes it easier than ever for the greedy to succeed. I am somewhat jealous of the bankers’ good intelligence, for they knew to take it all. I have made the opposite mistake twice and at great personal cost. If only I had known at the time, that the world could give $.02, then I might have chosen more wisely. Here is the deal: Smart guy realizes world could care less about anything, therefore, he understands that he should take all that he can. Dumb guy thinks world cares and desires to make world a better place, therefore, he takes less and believes in greater mission. End result: world goes to hell, but smart guy has millions and dumb guy has nothing