I recently (September 2011) learned what happens if there’s a fatal accident on your property in Kathmandu. It’s what would happen in a rural village.

A boy hired to apply concrete facing on a house fell from the second floor and was killed. The boy’s father knew the homeowner did nothing that contributed to the accident, but in Nepali culture he must provide compensation because the boy would have supported his parents in their old age. Because the father has a good heart and knows the homeowner does not have much money, he requested only about two years’ wages compensation, which the homeowner had to borrow and is now working to repay.

After I wrote about Truck Drivers’ Insurance in Nepal I was asked how big is the fine for killing someone and how much for injuring them. The fatality fine is too large relative to what a driver can earn. That’s why they join the insurance club. There isn’t a fixed fine for causing injury. The problem for the driver is he becomes responsible for paying the victim’s medical costs and compensation for loss of earnings, etc., which gets complicated and unpredictable. If nobody observes the injury he simply drives off. If he may be caught it’s better for him to get the definite outcome, the fine for a fatality. Vehicular homicide is always considered an accident.

Another comment was: “The drivers must feel somehow insulated from reality up in the cab or how could they back up and run over someone on purpose. Perhaps to the Ranas other people are just animals.” The Ranas ran Nepal for more than a century before the king regained control in 1951. They set the example for how to drive because they were the only ones who could have motorized vehicles. They established that killing someone in this way deserves only a fine.

The Ranas used tax-gatherers to collect half or more of the peasant farmers’ annual production. They rarely saw anyone other than their entourage and they did act as if the rest of the population were animals. You do not treat an animal standing on the road with any courtesy, not in a hierarchical society, anyway. The Ranas’ vehicles were driven by their resentful and/or prideful servants who would have treated the “animals” not with indifference but contempt.

Nepal still has a highly status-conscious culture. The Ranas established a caste system that encompassed not just them and other Hindus, not even just tribal folks who were not Hindu, but also foreigners. There was a hierarchy of tribes as well as the traditional Hindu caste hierarchy. This aspect of Nepali culture has changed less than I imagined. I did not at first realize there is a hierarchy because we relatively very wealthy Westerners are treated as high caste.

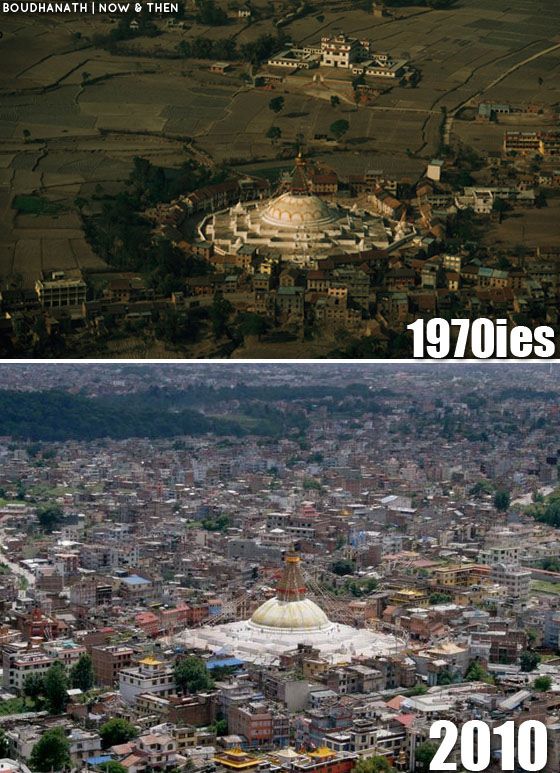

I also misunderstood Kathmandu Valley culture because the village culture I saw first on mountain treks is more egalitarian. The Ranas had little influence there because there was little for them in that harsh environment. The majority of people in the Valley now are fairly recent arrivals. If they can get a motorbike, they are suddenly more powerful. They’ve acquired what the Ranas had, the ability to intimidate. Add these dark cultural legacies to the very low level of common sense among Nepalis, G says, and you have the explanation of Kathmandu traffic.

G went to a driving school when he got a motorbike. The owner said he need not take lessons, for Nrs 3,000 (a little over $40, an average monthly wage) he would get G a license. G said he wanted to take lessons and pass the test. The owner said he might fail and would have to wait six months before he could take it again. G persisted and passed.

Another question prompted by “Truck Driver’s Insurance” was about the overall legal system, which used to be controlled by the king, then by parliament. I’ve seen no discussion of an independent judiciary under the new Constitution. The politicians want to remain safe from prosecution for corruption unlike in India, which is also famously corrupt, where a very strong independent judiciary was inherited from the Brits. India’s Telecom Minister is in jail for corruption right now, his boss the Minister of the Interior is under indictment, and the Prime Minister may also be indicted.

A villager we talked with yesterday said: “We don’t need democracy, what we need is for criminals to be punished.” That’s a common theme. We keep hearing complaints about the breakdown of law and order. Westerners are safe so long as they remain in the tourist areas during daylight because there will be severe retribution for messing with them. Nepalis, however, are not safe from each other anywhere after dark and business people are not safe period. Three men were arrested yesterday for demanding protection money from more than 50 business owners in Kathmandu.

Village style social pressure for good behavior has not yet been replaced in Kathmandu by an urban rule of law. The distressing results illustrate why urban societies need an effective central government.