Why isn’t our monetary policy working? Set and executed by the Fed, it aims, by expanding or contracting the supply, cost and availability of money, to increase economic growth and lower unemployment, or cut inflation. But we are stuck in low growth and high unemployment despite an extraordinarily expansionary policy. What should we be doing?

The Fed continues to greatly expand money supply and it has for many years cut to unprecedented lows the cost of borrowing money. In “normal” times that encourages more borrowing. Those very low interest rates did fuel borrowing for investment in dot-com and real estate price boom/bubbles. They also enabled ongoing consumption that exceeded income. But then the bubbles burst and asset values collapsed. That was the start of “new normal” times. Borrowers no longer had sufficient assets to support more borrowing, greed was supplanted by fear, and folks began repaying existing debt while they still had income. Making borrowing more attractive is useless when borrowers cannot or will not borrow more.

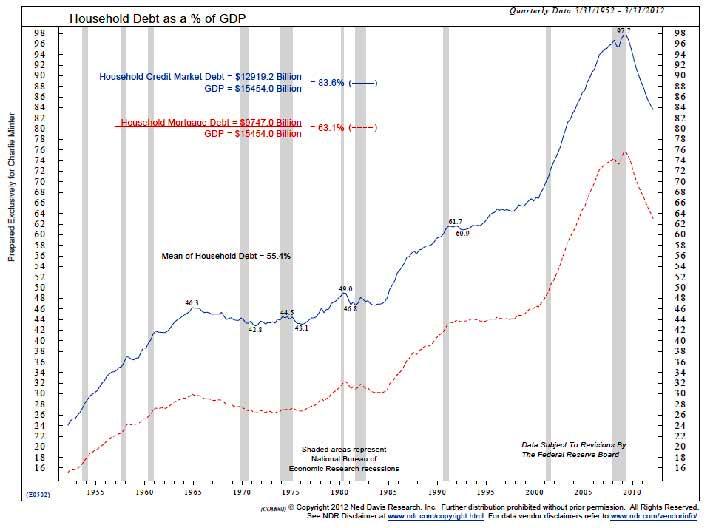

Expansive monetary policy is not working now because we are in a balance sheet recession. More specifically, we are in a household balance sheet recession. Mortgaged real estate is by far the largest asset of most households. While the real estate bubble was expanding they could get ever-larger mortgages and equity loans. Now they can’t. They can no longer continue borrowing to spend more than they earn. Since household spending accounts for 70% of USA GDP, that hurts all across the economy. The following chart illustrates the severe contraction of household debt in the last couple of years and suggests it will continue for at least another four years before it’s back to what could be a “normal” level.

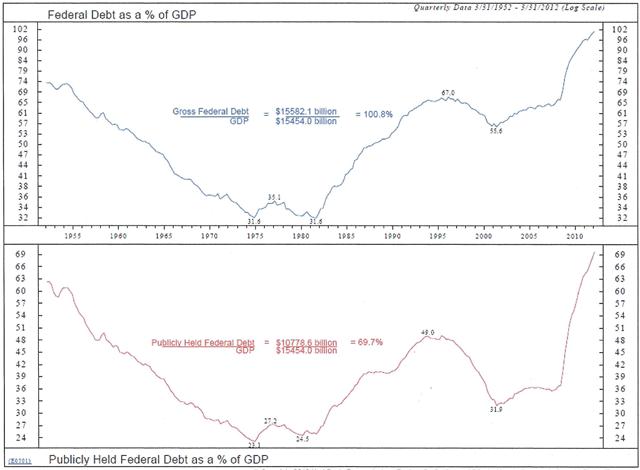

Lower household spending resulted in a contraction of economic growth, which shrank income growth and raised unemployment. That led to lower tax revenue and higher welfare program spending that compounds the preexisting imbalance between government income and spending. While our household debt drops, our public debt soars.

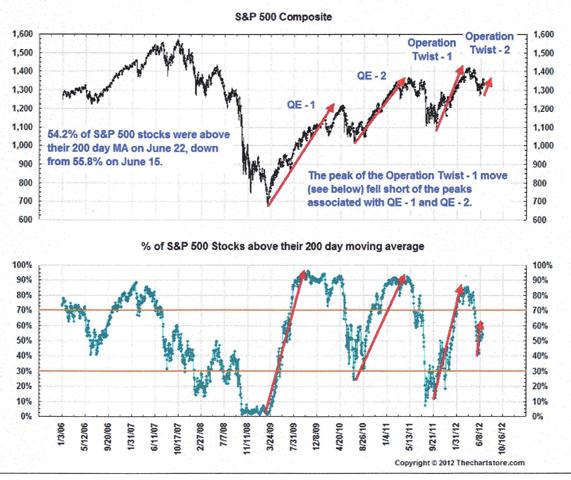

Low interest rates help in one important way by minimizing the cost of public debt. They hurt by minimizing the income of pension funds, insurance companies, and all fixed income investors whose spending commitments depend on a “normal” rate of return. Their “new normal” income is often significantly below their committed spending. And QE, the Fed’s injection of new money into the economy, helps equity investors only temporarily:

QE stimulates the confidence fairy but she stops dancing when QE ends.

Large enterprises that account for most of the S&P 500 are helped by low interest rates, they refinance existing borrowing at lower rates, but they have no need or desire to borrow for expansion. For one thing, they already have sufficient resources; more importantly, they do not expand production in face of shrinking demand.

The big banks are in better shape than when the real estate bubble burst. The Fed bought large amounts of their bad loans and the value of their assets now appears to be in better balance with their liabilities. But their assets may have much less value than appears. The value of property against which they made loans is now much lower. Derivatives they own based on those loans may have no value at all. Instruments they sold that insure against such risks may trigger payouts higher than they could make. Big banks are now afraid to lend to each other because they do not know if either they or their counter-party is solvent.

What will happen if we stay on this course? It looks like deflation first, then inflation. We’re getting lower-than-expected results or declines in GDP, job growth, retail sales, income growth, manufacturing production, core capital goods orders, vehicle sales and initial unemployment claims. We have uncertainty about tax rates, an imminent “fiscal cliff” and a dysfunctional congress. Commodity prices are declining worldwide, there’s a sovereign debt crisis in Europe, and ominous economic indicators in China, Japan, India, Brazil and other emerging nations. Collapsing aggregate demand could force producers to cut prices to find buyers. That would trigger rising unemployment and more defaults, bankruptcies and bank failures. Deflation would be followed by inflation if the Fed and other central banks expanded the supply of money far beyond the value of what it could buy.

No need to flesh out how bad that could be. What can we do to avoid it? How can we stimulate growth and employment?

The indicated strategy is the opposite of our apparently emerging fiscal policy. The National Association of Manufacturers and others estimate the Budget Control Act of 2011 which mandates $1.2 trillion of Federal spending cuts between 2013 and 2021 will cost one million jobs in the private economy by 2014, drive unemployment up 0.7% and cut GDP growth by 1%. Federal spending in 2011 was $3.753 trillion of which $1.233 trillion, the spending for goods and services, was added to GDP. Transfers, e.g., Social Security and interest on the debt do not add to GDP, only if they are used for private spending. Two thirds of Federal spending for goods and services, $835 billion, was for national defense. If, as seems probable, cutting that spending will cut GDP growth and employment, the opposite, increasing that spending, should increase economic growth and employment.

It would not be productive to stockpile more weapons or borrow more money to wage wars in Afghanistan and elsewhere, but there are productive alternatives, investments in the same class as President Eisenhower’s 1956 National Interstate and Defense Highways Act and his 1958 National Defense Education Act in response to the Soviet Union’s Sputnik launch. We are now under-investing in transportation infrastructure and education, greatly so relative to China, Singapore and others, but our greatest vulnerability is availability and cost of energy. Failing to address that will make our defense impossible. Fixing it will have great competitive benefit.

The Department of Energy funded a recently published detailed analysis of the extent to which renewable energy supply can meet US needs over the next several decades. Its most key finding is: “Renewable electricity generation from technologies that are commercially available today, in combination with a more flexible electric system, is more than adequate to supply 80% of total U.S. electricity generation in 2050 while meeting electricity demand on an hourly basis in every region of the country.” See: http://www.nrel.gov/analysis/re_futures/

This means we can eliminate our greatest vulnerability, which could happen soon, e.g., by Iran blocking the Gulf, and must happen when the wells run dry, and by doing it first we would create an enormous global market for our solution. Why would we not not work with utmost urgency to achieve that? Enough money is available for the private sector’s share of the investment and the Fed would create more if required. The US government would have to take on additional debt to fund its share but there would be no problem selling the bonds because the US is already considered the least unsafe borrower. This investment program would be viewed positively, unlike the existing structural budget deficit and it’s the perfect time for such an investment because borrowing costs are so low.

But we cannot do this with a Congress that will not take action, a President whose leadership does not compel action, and a citizenry that does not understand what to demand.

For much more detail on monetary theory and what the Fed and other nations’ central banks do and why, see my earlier post at:

Monetary policy aims only to manage short-term aggregate demand. That’s not enough right now. The world has changed. Change is accelerating. We must correspondingly change our economy. That requires structural change in fiscal policy (government revenue collection and spending). The dynamics are well said here: “restoring stability and growth is only partly about reviving short-term aggregate demand. It is also about structural reform and re-balancing, which comes at a cost. Achieving a sustainable pattern of growth requires choices that affect not just the level of aggregate demand, but also its composition – for example, investment versus consumption.” from Michael Spence’s post: http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/clarity-about-austerity

Central bank balance sheets now contain $18 trillion of assets, about 30 percent of global gross domestic product, double the ratio of a decade ago.