I was quite startled to learn that our Constitution has a stated aim to protect the “opulent minority.” I was impressed when I studied our system of government for my citizenship exam. Now I realized that I didn’t understand the system’s history or implications.

I started with Robert Dahl’s excellent How Democratic is the American Constitution? Daniel Lazare’s The Frozen Republic opened my eyes wider. Then I read Colin Woodard’s enormously helpful America Nations – A History of the Eleven Regional Cultures of North America.

Woodard began his career in Eastern Europe when the Soviet Union was collapsing. He noticed that the boundaries of Hungary, Poland and other nations bore little or no relation to the ethnic and cultural realities. Groups within those countries had always been rivals and people across borders shared a culture and long history.

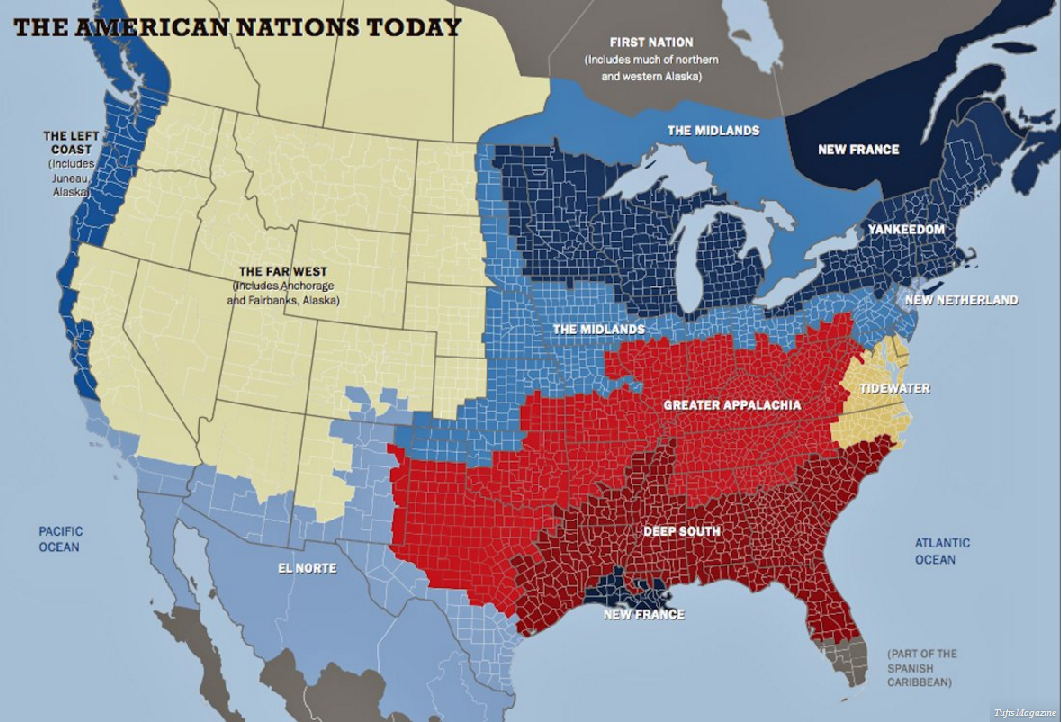

That got Woodard thinking about cultural rivalry within our nation. The South versus the North, the coasts vs the heartland, those grossly simplified divisions don’t explain the reality. Cultures that came from England, France, Spain, the Netherlands and so on were significantly different and those cultures remain powerfully alive.

Our values and the behavior they motivate are much more those of eleven distinct people than of fifty States, or of an homogenous population with shared values.

What are the implications?

The Constitution’s first words are “We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect Union.” Coming in the recent past from very different cultures with very different values, many of the delegates did not want union but to be left alone. Those who wanted union had very different ideas about its form. The great majority of the population was not consulted, certainly not those whose land had recently been invaded.

The Constitution that resulted from all the necessary compromises results in an ongoing contest between only two major parties.

My conclusion before I read Woodard’s research was that since the Republican Party has been taken over by a tiny minority of the most wealthy Americans in alliance with fundamentalist Christians and anarchists, “something-other-than-progressives” must take over the other Party. But that would result in even more extreme gridlock.

The Democratic Party must not shift to the far left to balance a Republican Party that is moving further and further to the far right. It must find a position that accommodates the diverse values of a majority of people across all our eleven nations.

Our world is constantly changing, so our policies and programs must, too. Sometimes a conservative brake on changes will be best, other times major changes will have grown urgently necessary. And the priorities of neither major party will permanently align with those of any of our eleven nations.

Some of us wage war on “invasive species”, plants, insects, fish, rodents, mammals, any form of life that “does not belong here.” Some of us reject people who arrived recently and “don’t belong.” But as the world inevitably changes, life forms inevitably move.

Recent linguistic research indicates that the first people in North America did not come directly from Siberia across the Bering Strait 12,000 years ago. People from Siberia had been living in Beringia for around 85,000 years. When the ice melted and their habitat was flooded 12,000 years ago, some came here. Others went back to Siberia where they perhaps no longer “belonged”.

Those who came here formed into tribes, some peaceful, some making war on each other. We think of those Native Americans as being decimated by “the white man” as if a single invasive species destroyed them. In fact, it was a variety of new species, eleven major ones, that set up an entirely new form of government which excluded them.

What we need to do now is figure out how we can use that system of government to better represent the people of the eleven nations who we speak of collectively as “Americans.”

We are not alone in facing this challenge and we have had governments that better represented us all in the past. We can have such a government again. We’re in a much better position than, for example, Nepal. Politicians there continue to wrangle without visible progress over what structure of government could represent all Nepalis, not just the Brahmin elite.

Nepal’s politicians cannot even start to learn how to govern until they choose a structure. Ours could start governing effectively right now. We must make them do so.