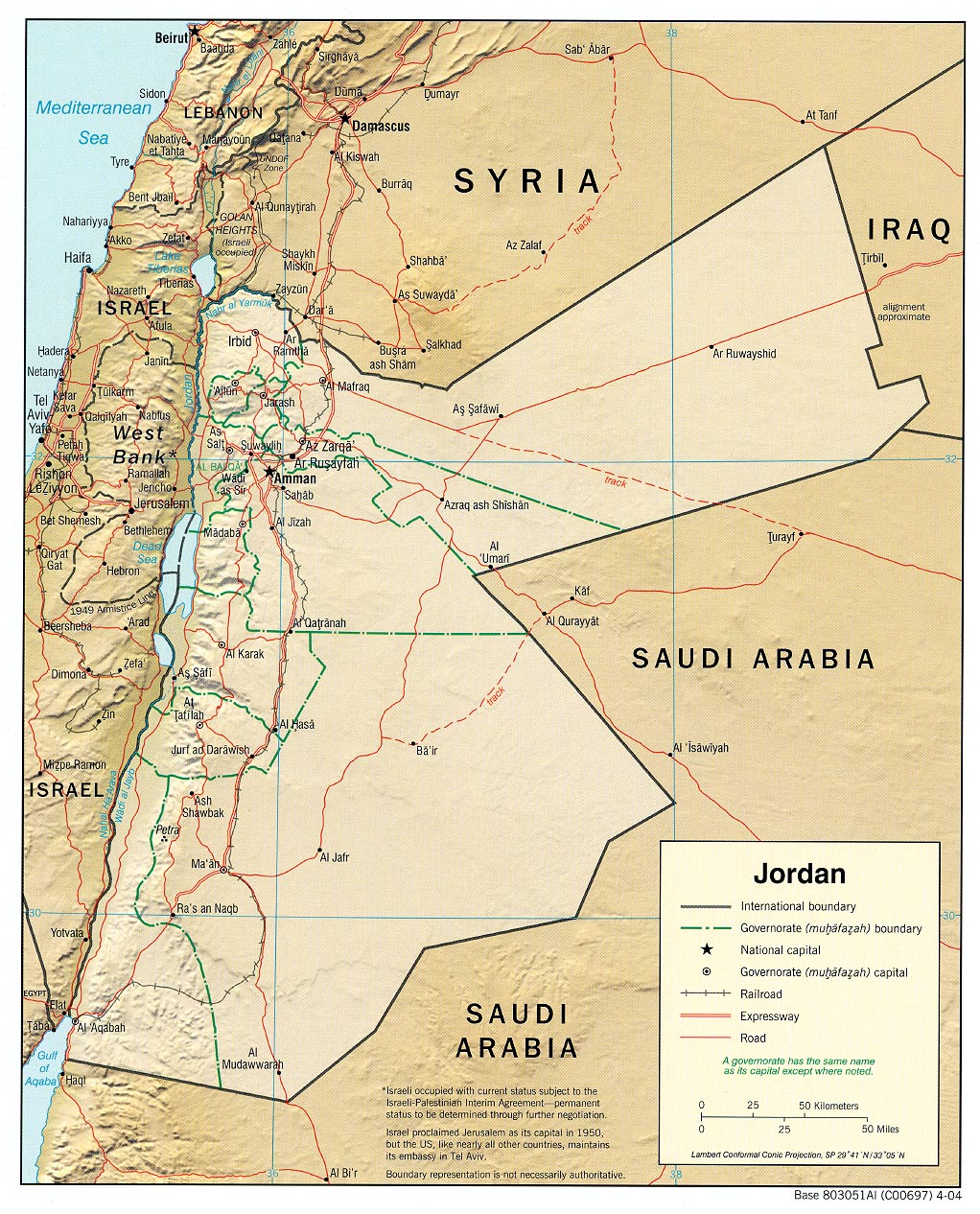

Jordan, Israel and Palestine coexist warily in what Christians, Jews and Muslims call the Holy Land. Jordan is east of the Jordan River with Syria in the north, Iraq in the north-east and Saudi Arabia in the south. It was populated mainly by tribal Arabs when its borders were set. They are outnumbered now by Palestinians who fled since Israel’s establishment at the end of WW2.

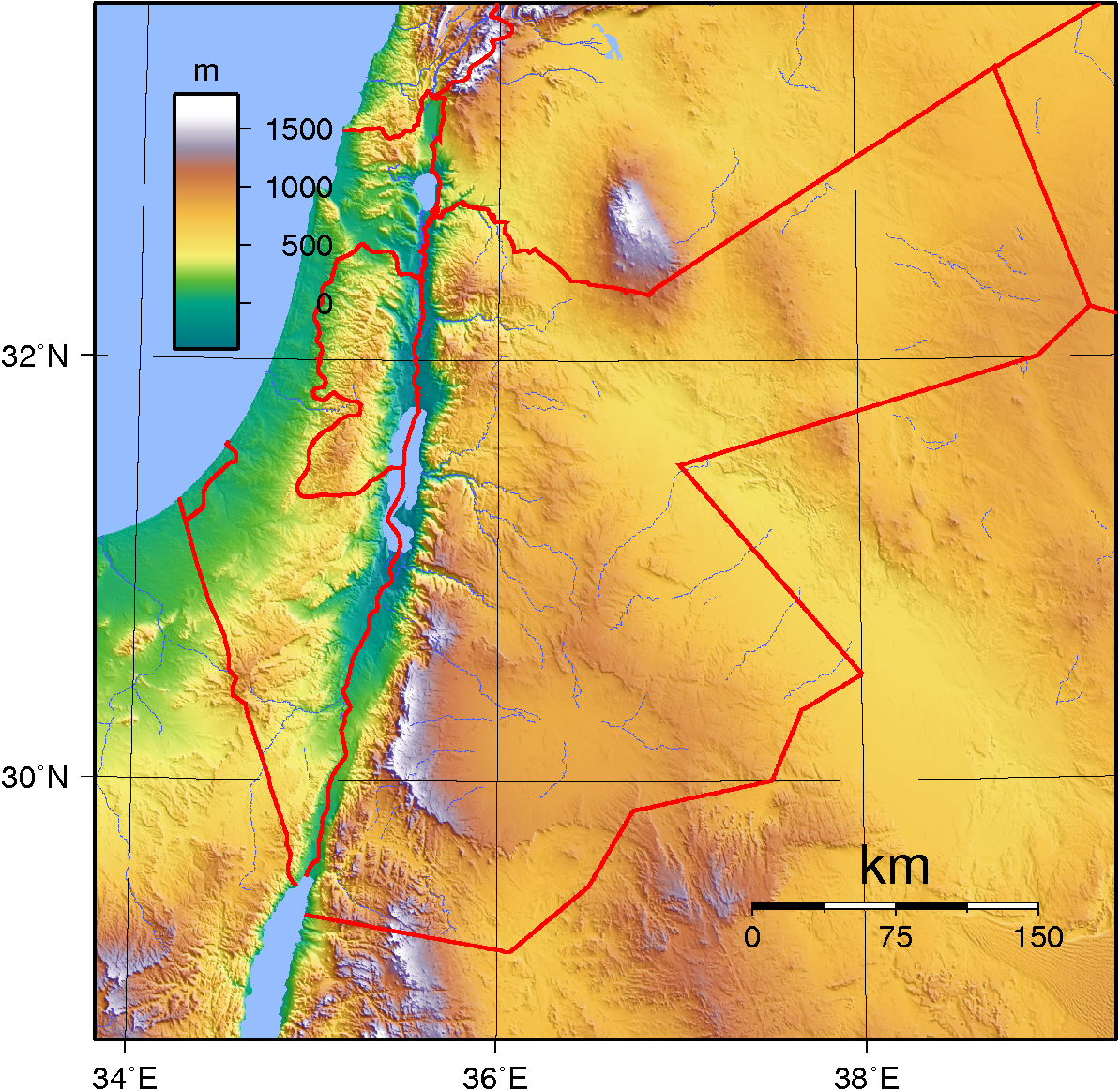

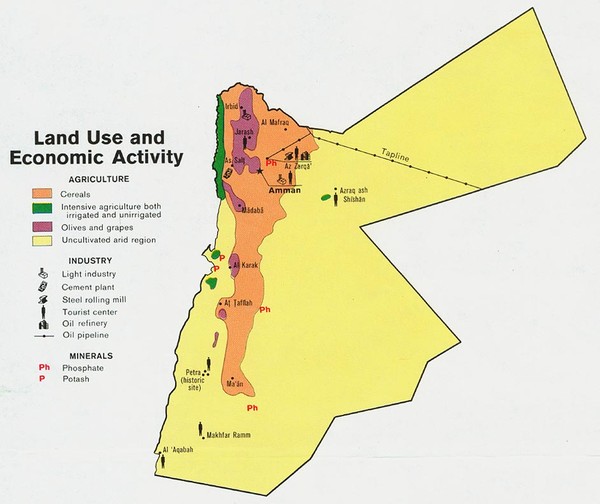

Most of Jordan is plateau and most of that is desert rising gradually in the west to villages in the Jordanian Highlands. Further west, the highlands descend into the north-south rift valley down which the River Jordan flows through the Sea of Galilee and the Dead Sea to the Red Sea. Only about 2% of Jordan’s land is arable, half of it permanently cropped. There is no oil, insufficient water, few resources of any kind that humans value.

Jordan is landlocked except where the Gulf of Aqaba gives it access to the Red Sea. Aqaba was a major Ottoman port connected to Damascus and Medina by the Hejaz railroad. The WW1 Battle of Aqaba was key to ending the Ottoman Empire’s 500 year long rule of Arab lands.

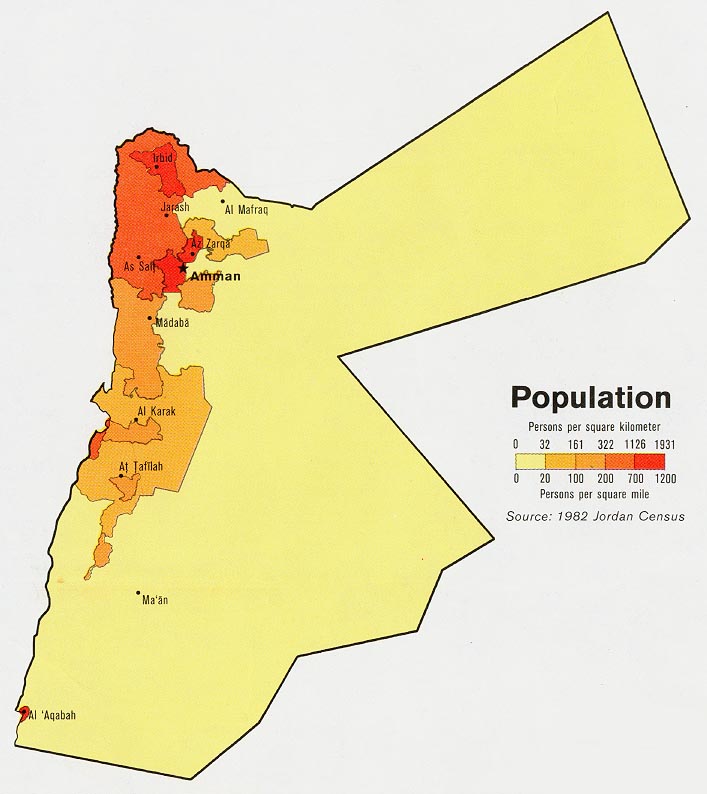

Jordan’s population is around 8 million, about half of whom are Palestinian refugees or their descendants. It was 400,000 in 1948, about half of them nomadic, but when 700,000 Arabs fled or were expelled that year from what became Israel, many went to Jordan, and many more came later.

Since the 2003 war in Iraq, a million refugees have also arrived from there, and, since 2012, more than half a million refugees from Syria.

About 92% of Jordan’s population is Sunni. About 6% is Christian (the CIA says 2%), down from 30% in 1950 primarily because of Muslim immigration. Well educated Christian Arabs dominate business. A 1987 study showed half of Jordan’s leading business families to be Christian.

Since most of Jordan is desert, the population is highly concentrated in the northwest.

When Britain gained control of Jordan and Iraq at the end of WW1 it appointed sons of Hussein bin Ali as their rulers. Britain had promised Hussein rule of all Arab lands in return for leading the Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire. Faisal ibn Hussein became ruler of Iraq and his brother Abdullah ibn Hussein ruler of Jordan.

Abdullah I established his government in 1921. Britain granted nominal independence in 1928 but kept a military presence, control of foreign affairs and some financial control. At the end of WW2, although the US wanted Israel to be established first, Britain granted Jordan full independence. US President Truman recognized the independence of Jordan and Israel on the same day in 1949 considering them twin emergent states, one for refugee Jews, the other for Palestinian Arabs displaced as a result.

Abdullah I had represented Mecca in the Ottoman legislature from 1909 to 1914 but allied with Britain during WW1 and played a key role in the Arab revolt. He ruled as an autocrat.

Recognizing the inadequacy of resources within Jordan’s borders, Abdullah hoped to reestablish and rule Greater Syria, the Ottoman district made up of present day Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan. He invaded Palestine with other Arab states in 1948, occupied the West Bank and formally annexed it in 1950. Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Syria then demanded Jordan’s expulsion from the Arab League but were blocked by Yemen and Iraq. Abdullah was never trusted again by other Arab or Jewish leaders. He was assassinated in 1951 by a Palestinian who feared he would make peace with Israel.

Abdullah I was succeeded by his son Talal who had to abdicate the following year because of mental illness. His son Hussein who was educated in Egypt and England then ruled until his death in 1999.

King Hussein recognized that while the borders Britain had set for Jordan with Syria, Iraq, and Saudi Arabia could not be eliminated as his grandfather had hoped, they might with negotiation be improved. In 1965, he was able to make a deal with Saudi Arabia that gave Jordan an additional 11 miles of coastline on the Gulf of Aqaba to expand its port facilities. The great problem was Jordan’s border with Palestine.

From 1950, near the end of Abdullah’s reign, Jordan administered the Palestinian West Bank. Then Israel invaded and seized it in the 1967 Six Day War. What should Hussein do? He continued to claim the West Bank until 1988 despite its occupation by Israel. He relinquished it to the Palestinians then, and signed a peace treaty with Israel in 1994. Jordan is still only the second Arab nation to do so. Egypt was the first in 1979.

Over the course of his long reign (1953-99) , Hussein kept negotiating for peace and managed to establish a relatively solid footing for Jordan despite competing pressures from great powers and massive immigration from Palestine, but his strongly pro-Western policy meant that he was never entirely trusted by other Arab leaders.

Hussein made less progress on Jordan’s economy, which is among the smallest in the Middle East. Because there is so little fertile land, agriculture accounts for only 3% of GDP. Phosphate mining and other industry is around 30%. Trade, finance and other services make up the balance. Jordan depends largely on foreign aid, of which the US is the main provider, and the government employs at least a third and perhaps more than half of all workers.

Hussein was succeeded by his son, Abdullah II, who was educated both in England and the US and who served in the British army as well as both Jordan’s army and air force. He has focused on religious coexistence, Israeli-Palestinian peace as well as building a powerful Jordanian military, and especially on Jordan’s economy.

Abdullah II worked for several years to get agreement on a project that was first proposed in the late 1960s as part of peacemaking between Israel and Jordan. The Red Sea–Dead Sea Canal will provide desalinated drinking water to Israel, Jordan and Palestine, replenish the Dead Sea whose surface area has shrunk 30% in the last 20 years because nine tenths of the Jordan River’s flow is diverted for crops and drinking, and generate electricity. In late 2013 the three nations reached agreement to go ahead with the project.

What Abdullah II has not done is make Jordan’s government more democratic. It is a constitutional monarchy in which the king is Head of State, Commander-in-Chief, and appoints the Prime Minister, Cabinet and regional governors and 75 members of the Senate. The House of Representatives and other Senators are elected but elections have been seriously rigged. A new law in 2012 prohibits parties based on religion. That led the Muslim Brotherhood and others to boycott voting.

Although its military is strongly supported by the US, UK and France, Jordan is also a founding member of the Arab League whose goal is to “draw closer the relations between member States and co-ordinate collaboration between them, to safeguard their independence and sovereignty” and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation whose goal is to “safeguard and protect the interests of the Muslim world in the spirit of promoting international peace and harmony.” Jordan is also an active member of the UN and provides the third highest participation in its peacekeeping missions, and is in the European Union’s program to bring the EU and its neighbors closer.

Jordan’s ruling dynasty has good international relations and is well accepted by Jordanians despite autocratic rule, massive immigration of refugees, an economy that is not self-sufficient, and high unemployment especially among young adults.

Because Jordan’s population is so heterogeneous, it is not a nation in the sense of a potentially genocidal homeland. It is very much a state, however, even though it has no natural borders with Syria, Iraq or Saudi Arabia. They accept the ones drawn by colonial powers almost a century ago. It does have a natural border with Israel and Palestine, the Jordan River, that is now accepted by all parties although the status of Palestine itself remains unresolved.

There is much to be learned from Jordan’s history of governance.