The first post in this series noted our Constitution’s intent to “protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.” The economy then was subsistence farming in many areas, commercial agriculture in others, especially the South. The opulent minority were great landowners and most everyone else was poor. There was no middle class.

If we were drafting a Constitution now we would also seek to protect the minority in the middle from excessive influence based on great wealth. The distribution of incomes throughout society would be an important indicator of whether that influence had grown excessive.

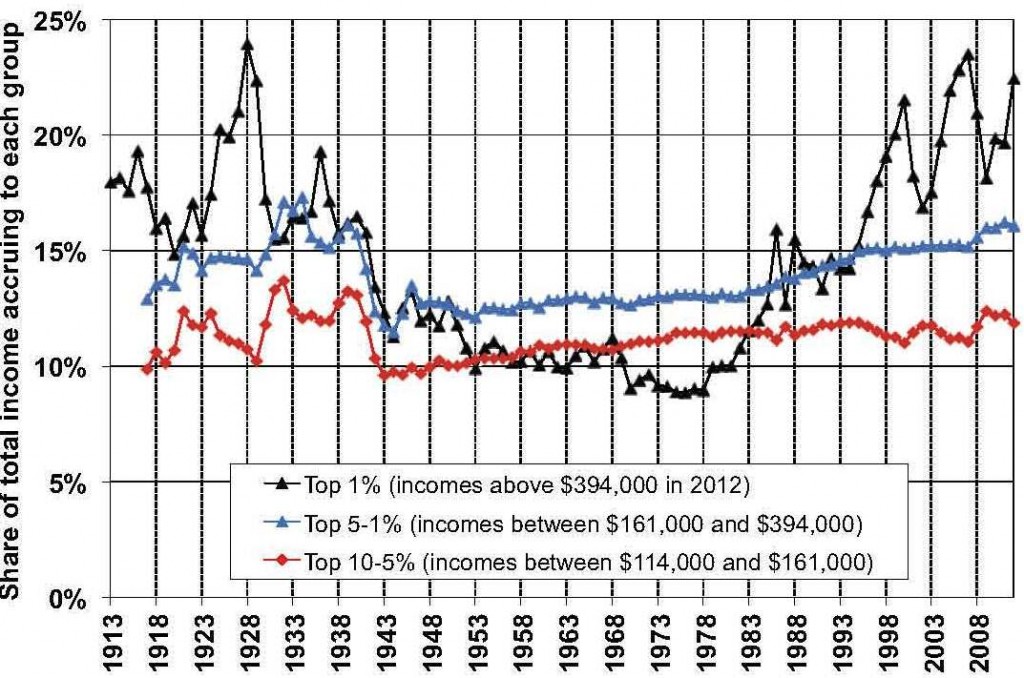

In this research paper Emmanuel Saez shows how,”the top decile share [of pre-tax income] has increased dramatically over the last twenty-five years [and] in 2012 is equal to 50.4 percent, a level higher than any other year since 1917.” But it’s not just that the top 10% gets more than half of all income, the top 1% gets close to a quarter.

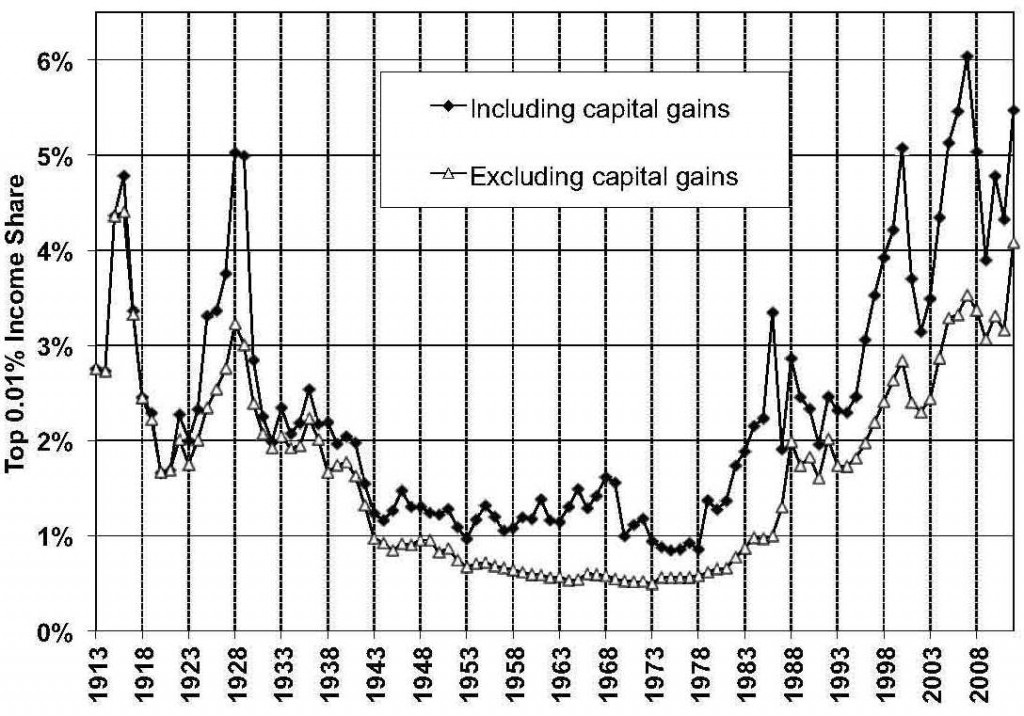

And the very greatest gains go to the top 0.01%, i.e., one in one hundred of the one percent. That was 16,068 folks in 2012 with annual incomes over $10,250,000. We might imagine most of that income was stock market gains but as the chart shows, while a large and fluctuating amount was from capital gains, that tiny minority also got extraordinarily higher income from what we think of as wages.

Is that OK or are we seeing excessive influence? This report from the Pew Research Center indicates that 55% of Republicans consider our economic system fair to most people and “four-in-ten Republicans termed the gap either a small problem (22%) or not a problem at all (18%).” Three in five Democrats said the gap is a very big problem. Billionaire Tom Perkins, who feels he’s being treated the way Nazis treated the Jews, considers those who believe inequality has gone too far are the problem.

A growing body of research indicates that high inequality is in fact harmful to both an economy and a society. An obvious issue is if most of society’s income goes to a small minority, economic activity slows and everyone suffers. Less obvious is the impact of what society’s income is not used for — government ceases to serve the majority.

One example. The ongoing study reported here shows the USA is now 33rd among nations in internet download speed, almost equal with Russia while Romania is two and a half times as fast. We’re 43rd in upload speed while Kazakstan is half again as fast. How did that happen? We let cable and telecom companies merge their way to oligopoly or even monopoly. They have little incentive to invest in better service because they have little competition.

Imagining that private businesses automatically deliver the best results, we don’t notice that government regulators have been captured by corporations and consequently provide negligible oversight.

In previous posts I explored how deregulation of our financial sector led to economic meltdown from which we have not yet recovered. Deregulation has in recent decades been shaped throughout our economy by the opulent minority. We should therefore expect them to get the benefits.

Several factors contributed. Getting elected now costs so much that politicians must depend on very wealthy patrons, which means they get legislative and regulatory changes they want. The Republican party used to be funded chiefly by upper middle-class professionals, the Democrats by labor union members. Both are now funded increasingly by corporations, their executives, and a tiny minority like the Koch brothers whose wealth is greater than the bottom 40% of all Americans combined.

Why has the rest of society taken no action? Partly because they haven’t noticed what is happening. Also, as US economist and social scientist Mancur Olson explained it in his 1965 book about Public Goods and the Theory of Groups, if everyone in a group would benefit from some change, individuals in the group are better off waiting for others to do the work. And large groups are at a disadvantage because their cost to organize is higher. The result is that large groups are less able to act in their common interest than small ones; and the corollary is, a minority can dominate the majority.

That is how the 99% in general and the middle class in particular allowed themselves to be disenfranchised — both our major major parties are now dominated by the opulent minority. So, does that mean those who are not among the opulent minority should form a third party?

French sociologist Maurice Duverger observed in the 1950s that third parties rarely succeed in “winner takes all” systems like ours. Ross Perot, for example, got zero electoral votes in 1992 despite getting 19% (almost one in five) of the popular vote. Fewer than 40% of voters wanted a pro-wealthy governor in Maine’s last gubernatorial election but two progressive candidates split the vote. That resulted in a governor the majority does not want.

The only third party that has succeeded in the US replaced an existing major party. The Republican Party replaced the Whig Party just before the Civil War. How? The Whig platform was economic reform and federally funded industrialization, but with no clear position on slavery. Federal infrastructure and schools did not have enough appeal for Southern voters so they realigned with pro-slavery Democrats. Northern progressives saw Whig candidates failing and switched to the increasingly vocal anti-slavery Republican Party, which became progressive.

Do we have any potentially successful third parties in the USA now?

The largest at this time is the Libertarian Party. They got 1% of the vote in the 2012 elections. They position themselves as more socially liberal than Democrats and more fiscally conservative than Republicans. They favor much lower taxes, no welfare, gun ownership rights, decriminalizing drugs and so on. Their belief, like Jefferson, is that liberty can survive only in small, homogeneous societies, a romantic fantasy at best. Today’s world is too complex. We and all our competitors have succeeded only with strong central governments.

Next is The Green Party, part of a worldwide movement advocating ecological wisdom, social and economic justice, grassroots democracy, and nonviolence and peace. Their best result at the national level was 2.9M votes or 2.74% of the total in the 2000 presidential election when Ralph Nader ran against unappealing major party candidates. That gave the election to the one he disagreed with more strongly. The Green ideal is noble but their platform does not stimulate the passions of a majority.

How about the Modern Whig Party? They pitch themselves as “a pragmatic, common sense, centrist-oriented party where rational solutions trump ideology and integrity trumps impunity.” Their goal is to represent those who are “unrepresented by the current political structure, fiscally responsible yet socially tolerant” because “American Liberalism and Conservatism are exhausted ideologies.”

But it’s not that the ideologies are exhausted: the problem is they are not at this time being represented by our major parties. What to do? History and logic tell us no third party will succeed in the US unless we change our “winner takes all” electoral system, which our elected representatives have every incentive not to do, so we must make one of the existing major parties represent the minority in the middle, or what would be better for everyone, rational fiscally responsible progressives.

The opulent minority achieved their goal by taking over the Republican Party in opportunistic alliance with those who want their understanding of Christian teachings to govern law and public policy, and those opposed to a strong central government. That leaves the Democratic Party which, like the pre-Reagan Republican Party, has no clear focus and is therefore a takeover candidate.

I will explore in a future post how that might be done (and the Constitutional barriers). One possibility is via an issue that is not supported by either major party, like ending slavery in the 1860s. Another is to act when misery is so great that dramatic change is unavoidable, like the Great Depression in the 1930s. A mass movement with charismatic leaders is necessary in any case. That works even in societies less democratic than ours, e.g., the 1989 Czech Velvet Revolution and “color revolutions” in the former USSR, the Balkans, North Africa and elsewhere.

We can either identify a major change that enough people passionately want, or wait for enough people to be in enough misery. Let’s work on the first approach.