The leader of the self-declared Islamic State vows they “will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes-Picot conspiracy,” utterly destroying “borders that were drawn by malicious hands in lands of Islam.” It’s important to understand that “conspiracy.”

When the Ottoman Empire joined Germany in WW1, Britain conquered Palestine because it needed a route to move large forces fast from the Mediterranean to the Persian Gulf to defend its interests in India. Britain then made a secret pact with France and Russia, the Sykes–Picot Agreement, about how they would divvy up the Ottoman Empire’s Arab provinces at war’s end.

Britain got present day Israel, Palestine, Jordan and southern Iraq. France got south-eastern Turkey, Syria, Lebanon and northern Iraq (Britain later managed to get northern Iraq, too, when oil was discovered there). But for the Revolution that overthrew its Tsar, Russia would have gotten Armenia and north-eastern Turkey.

This schematic of the original 1916 agreement shows the area Russia would have occupied in green, the area France would occupy in dark blue and the area it would control administratively in light blue, the area Britain would occupy in dark red and what it would administer in light red. The purple areas were to be international zones.

The agreement was endorsed by Hussein bin Ali, the leader of Hejaz, who, in return for leading an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire, was promised a post-war Arab empire from Egypt to Persia excepting only Britain’s possession of Kuwait, Aden and the Syrian coast. Britain considered Hussein the Arabs’ leader because Hejaz incorporated Islam’s holiest sites, Mecca and Medina.

Hussein declared himself King at war’s end. Then in 1924 he declared himself Caliph, political and religious successor to the prophet Muhammad and leader of the entire Muslim community. His arch-rival, ibn Saud, attacked and defeated his forces and unified what is now Saudi Arabia.

The area defined as an international zone in the Sykes-Picot Agreement that is now Israel and Palestine was defined that way because Britain’s Prime Minister had declared himself “very keen to see a Jewish state established in Palestine.” Israel would, it was thought, be too small to defend itself so it would need the international community’s protection.

Promises were made separately and in secret to Arab and Jewish leaders during the war that were mutually contradictory. One or the other had to be abandoned.

In 1917, Lord Balfour wrote a Declaration that Britain and its allies were committed to establish Israel. Then in 1918, Britain and France pledged to “assist in the establishment of indigenous Governments and administrations in Syria and Mesopotamia by setting up national governments [chosen by] the indigenous populations.”

Perhaps Arab leaders could have accepted a homeland for Jews who wanted to “come home” but “national governments chosen by the indigenous populations” negated the unified Arab homeland they had been promised.

This is why, speaking in Iraq, ISIL’s leader said: “We have now trespassed the borders that were drawn by the malicious hands in lands of Islam in order to limit our movements and confine us inside them. And we are working, Allah permitting, to eliminate them (borders). And this blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes-Picot conspiracy.”

The Sykes-Picot Agreement did not clearly define the territory that would become Israel. How big should it be? What lands should it encompass? The Old Testament had placed Israel’s tribes on both sides of the River Jordan, with the Manesseh tribe occupying not just the present day West Bank but also the East Bank, which is the fertile part of present day Jordan. The Agreement was also less than clear about the eastern border of Palestine.

In 1919, Chaim Weizmann, who later became President of the World Zionist Organization, made an agreement with a son of the King of Hejaz. It defined a Jewish homeland in Palestine and an Arab nation that would include most of the Middle East. That set Israel’s border within present day Jordan but the agreement was short-lived and would never have been acceptable to most Arab leaders.

In the end the League of Nations agreed in 1922 to a British Mandate for Palestine supplemented by a Transjordan Memorandum. Transjordan was the site of most battles during the Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule. The Mandate system was to provide government for the former Ottoman Empire territories in the Middle East “until such time as they are able to stand alone.”

The British protectorate of Palestine was to include a national home for the Jewish people while Transjordan was to be an Emirate governed semi-autonomously by Hussein bin Ali’s Hashemite dynasty, which was also to rule Iraq.

All these agreements, self-serving and/or well-intentioned, were based on ideas more than reality.

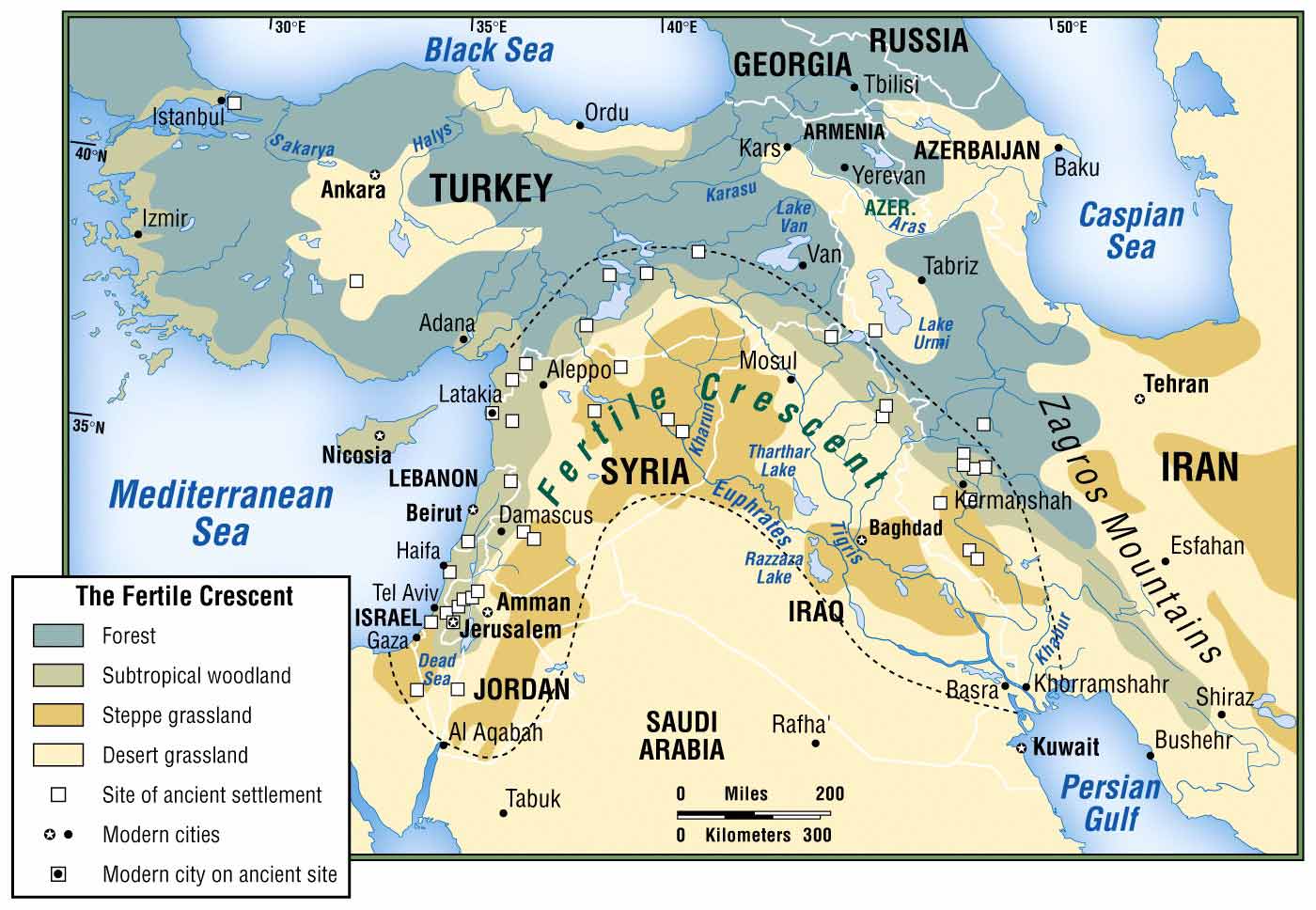

The best way to understand the reality is in terms of the Fertile Crescent, the relatively moist and fertile land where some of the earliest human civilizations flourished (the Crescent can also be defined to include Egypt.) Writing, glass, the wheel and irrigation all originated in this crescent.

The idea of nation states with borders to keep “us” safe and “others” out, the framework for the WW1 colonial powers and us now, is very recent. Empires in and around the Fertile Crescent rose and fell centered on areas of agricultural surplus.

Settled farmers, seasonally relocating herders, and wide ranging tribal folks changed their allegiance easily to the extent they felt any at all to their distant rulers. Religion was important as an inspiration for individuals — for rulers, it was a lever of power.

Entities we think of now as Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria and Turkey did not exist for most of history or had different definitions. Cultures long preexisted nation states and they have far more powerful impact on possible futures.