A few days ago, billionaire venture capitalist Tom Perkins wrote that the way progressives are starting to treat the super rich reminds him of how the Nazis treated the Jews. Soon after his letter was published in multi-billionaire Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street Journal, he had to apologize for his politically incorrect phrasing. He would have done better to quote James Madison, “Father of the Constitution” and author of the Bill of Rights.

When the Federal Convention of 1787 turned to the question “whether the republican form shall be the basis of our government,” Madison pointed out: “In England, at this day, if elections were open to all classes of people, the property of the landed proprietors would be insecure. An agrarian law would soon take place.”

The implication, he continued, is: “If these observations be just, our government ought to secure the permanent interests of the country against innovation. Landholders ought to have a share in the government, to support these invaluable interests, and to balance and check the other. They ought to be so constituted as to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.” (emphasis added)

A widely held belief has developed that the US Constitution offers protection for all minorities. That was not its intent. Madison’s much more limited aim was to protect the wealthy minority. Whether or not we like the result, we should recognize that our Constitution is working as intended.

How does it work? A republic is where power is held by elected representatives whose actions are bound by a Constitution. People in a republic vote for candidates who promise changes they like. The risk is that a small majority could make changes with unacceptable negative impact on the rest of the population. That’s why a Constitution is necessary, to prevent such changes by defining ‘unacceptable.’

I’m thinking about this because I’m reading Noam Chomsky. His diagnosis of why our government acts as it does, regardless which party is in power, feels spot on. He shows example after example of actions by our government that benefit the opulent minority and work against the interests of the majority here and throughout the world.

But Chomsky’s proposed solution is misguided. His central beliefs are that power corrupts and capitalism concentrates wealth, which, based on long first-hand experience and close study of history, are truths I hold to be self-evident. The question is, would his solution, anarcho-syndicalism, be better? Could it even work?

Anarcho-syndicalists are socialist libertarians. Like capitalist libertarians who enjoy President Reagan’s signature joke: “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help'” they oppose central power. The difference is anarcho-syndicalists say the inevitable concentration of wealth by capitalism exploits the majority.

Attractive increases in freedom are promised by both kinds of libertarians. In real life, however, the system does not scale. A libertarian (i.e., unregulated) society cannot protect shared resources or universal needs: local societies often manage local resources (e.g., forests) sustainably but resources managed by non-locals are polluted and/or depleted. And small societies cannot retain freedom: they cannot defend themselves against more powerful exploiters.

It is true that a fundamental problem for large scale enterprises is that central planning cannot work: there’s too much change to comprehend at the center. An ingenious programmer I once hired was directed to model how many tractors Soviet factories should plan to build. He tried combinations of many, many factors without success before at last seeing how to produce results that pleased the planners. How? By plugging the number of tractors that were going to be built, anyway.

Big businesses fail for the same reason – they lose contact with changes in their market.

Another problem is many things that start small seem destined to grow big but central planners too often fail to identify which are worth the investment. Small societies with property managed at the local level would make better choices but they lack the necessary resources. Today’s semiconductor and internet infrastructure, medical technology and etc required enormous investment.

So history tells us that democracies with a constitution tend to be better for people than autocracies, that market-based economies tend to deliver better results than centrally planned ones, and that capitalism seems essential to generate disruptive technology and deploy it on a large scale.

Speaking in Parliament in 1947, not so long after he lost the election following WW2, Winston Churchill famously said: “Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” The same looks to be true of capitalism in the economic sphere and nation states in the sphere of sovereign entities. They do all tend to concentrate power and wealth but the alternatives are worse.

So, “if these observations be just,” how can the non-opulent minorities who make up the majority get protection? Curtailing the inevitable abuses of power is achieved by incremental legislative changes that adapt Constitutional definitions to changes in society.

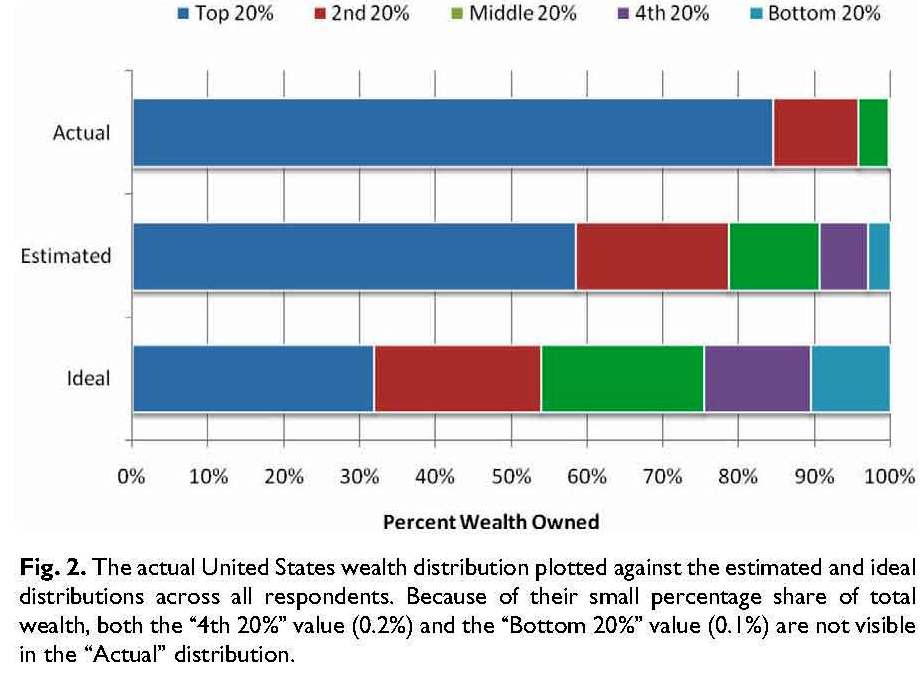

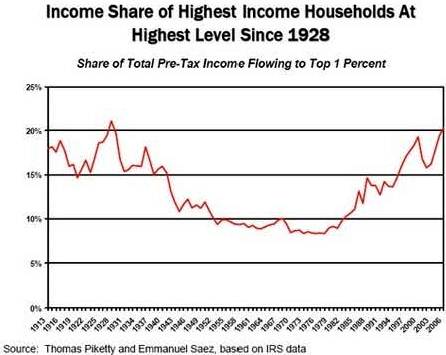

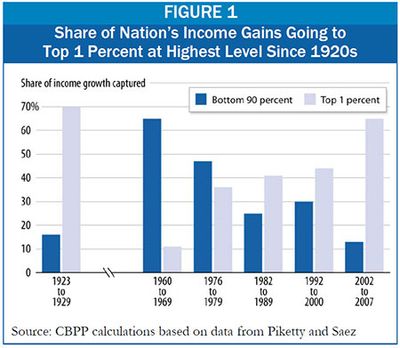

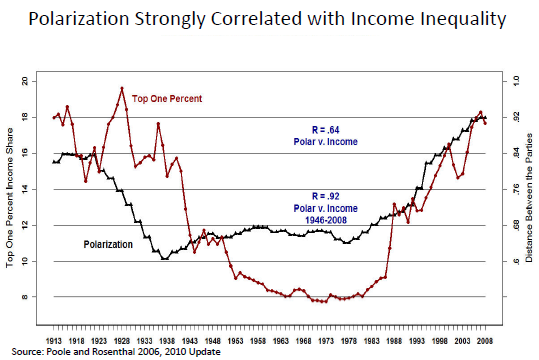

Because the fundamental structure of the system results in the wealth and power of the opulent minority always nudging the law’s evolution in their favor, other minorities must speak more loudly.

It is healthy that voices are now speaking loudly enough about too-high and rising inequality to be heard by Perkins and others. It indicates that our system is working as it should.