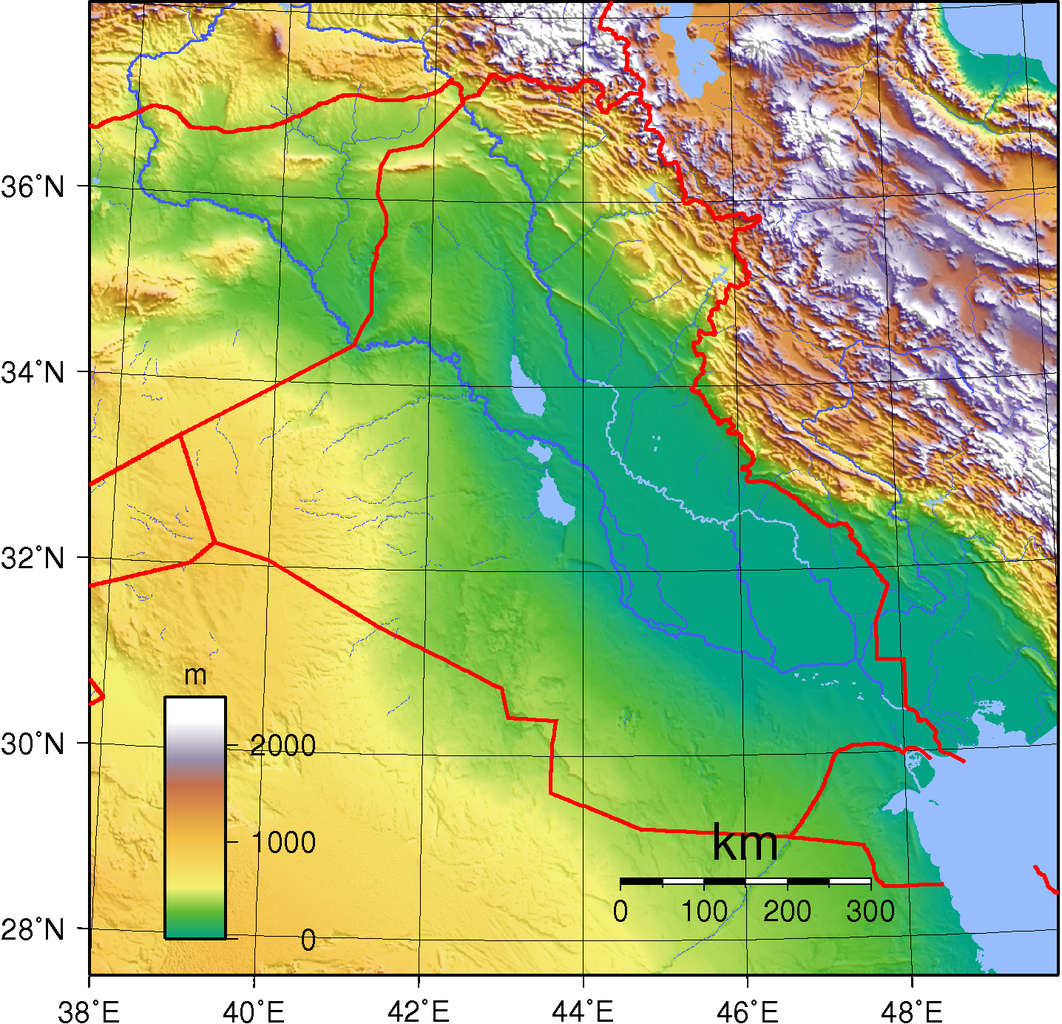

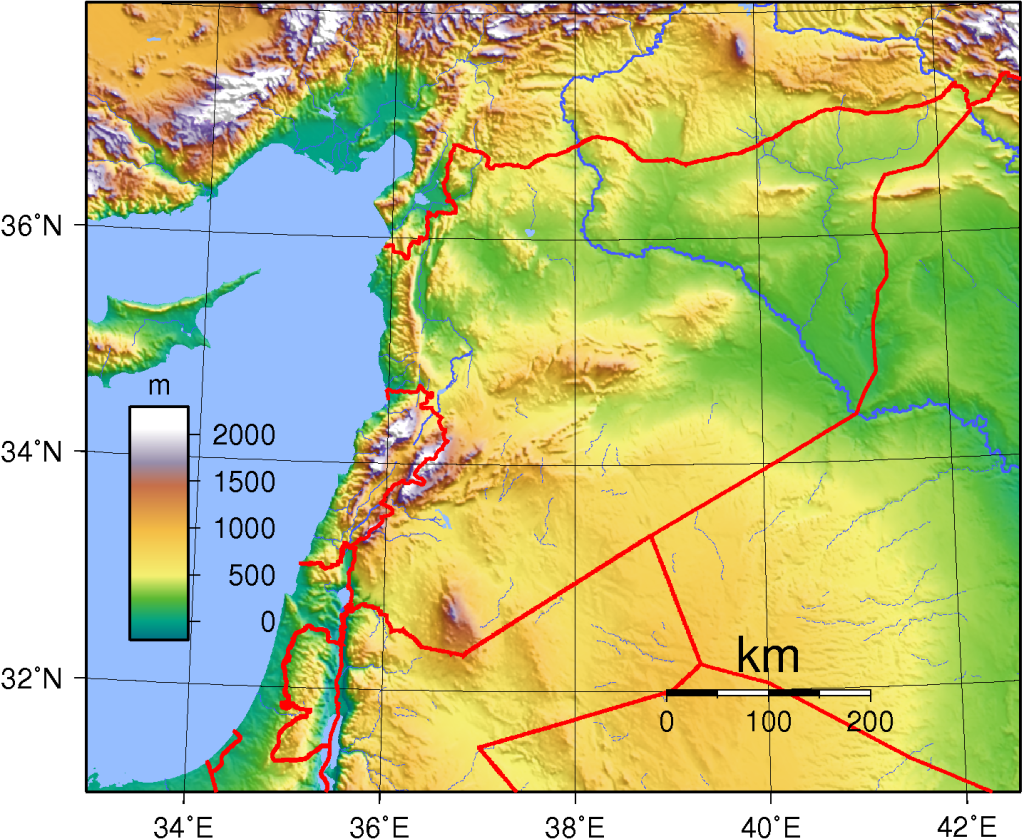

A stony plain west of the Euphrates inhabited by a few pastoral bedouins covers almost two-fifths of Iraq, which overall is about the size of California. Rolling upland between the upper Tigris and Euphrates is also largely desert. Highlands in the northeast provide Kurds with some grazing and cultivation but three quarters of all Iraqis live on an alluvial plain from north of Baghdad to the Persian Gulf through marshland from where the Tigris and Euphrates meet. Crops are increasingly limited south of Baghdad by salinity from river-born and windblown sand.

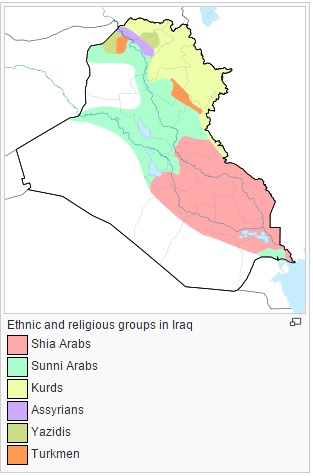

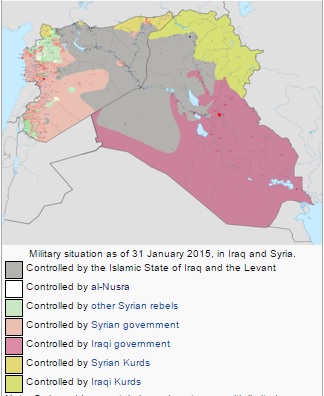

Three-quarters of Iraqis are Arabs, most others are Kurds. Most sources say two thirds of Iraqis are Shia, one third Sunni. But some claim there’s a Sunni majority. Kurds (17% of the population) are mainly secular Sunnis as are most Turkmen (around 5%). What is disputed is how many Iraqi Arabs are Shia or Sunni.

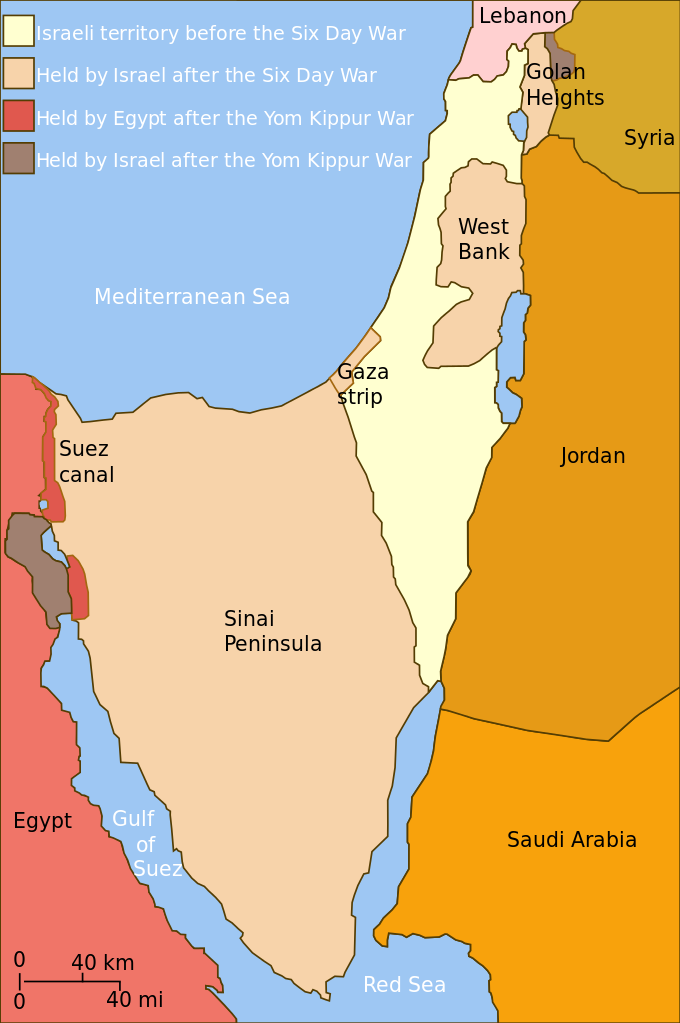

Christianity was brought to Iraq in the first century by the Apostle Thomas and Christians were in 1950 as much as 10% of the population. Many have fled and there are fewer than 1% now. The majority of Jews also fled after riots in 1967 when Israel captured Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula.

The forces at work in Iraq now have deep roots in the past. Centuries of battles between Persian and Eastern Roman empires that exhausted both paved the way for the Arab-Muslim conquest and the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate to be established in Baghdad in the 8th century. It soon dominated the Middle East, North Africa and Spain, and Baghdad became the leading city of the entire Arab and Muslim world. It was for five centuries Islam’s center of learning.

That glorious age came to an end in 1257 when Genghiz Khan’s Mongols swept in from the far northeast and sacked Baghdad. Sunnis had dominated throughout the Abbassid caliphate but Shia were able to convert others when it fell and more importantly, Sufi mystical Islam became popular in Iran, preparing the way for a subsequent Shia regime. In the mid 1300s, the Black Death halted recovery in Iraq and throughout the Middle East where fully a third of the population died (45-50% in Europe). Then in 1401, another Mongol warlord came, sacked Baghdad again and massacred the Assyrian Christians in northern Iraq.

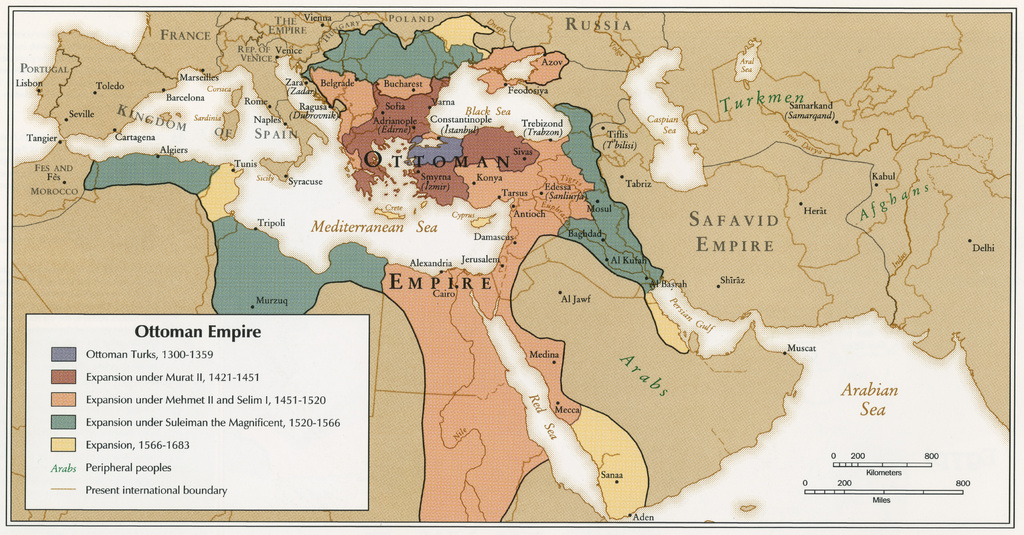

The Shia Safavid Empire that arose next in Iran began with a battle in 1499 led by their first ruler when he was twelve. He captured Tabriz two years later, declared independence from the Ottoman Empire (see below) and held most of present-day Iran by 1510. He set up a well administered theocracy that brought a nomadic society under control and financed an army that soon conquered much of Iraq, Turkey, the Caucasus, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The Safavid Empire ruled for more than two centuries, and enforced conversion to Shia under penalty of death.

The Ottoman Empire had been expanding in stages from the early 1300s. Their siege of Constantinople in 1453 brought the Byzantine Empire to an end and left them in control of trade with the Far East. They took Iraq from the Safavids in 1533.

Iraq remained a battle zone between the Sunni Ottoman and Shia Iranian empires from then until the Ottoman Empire finally fell at the end of WW1.

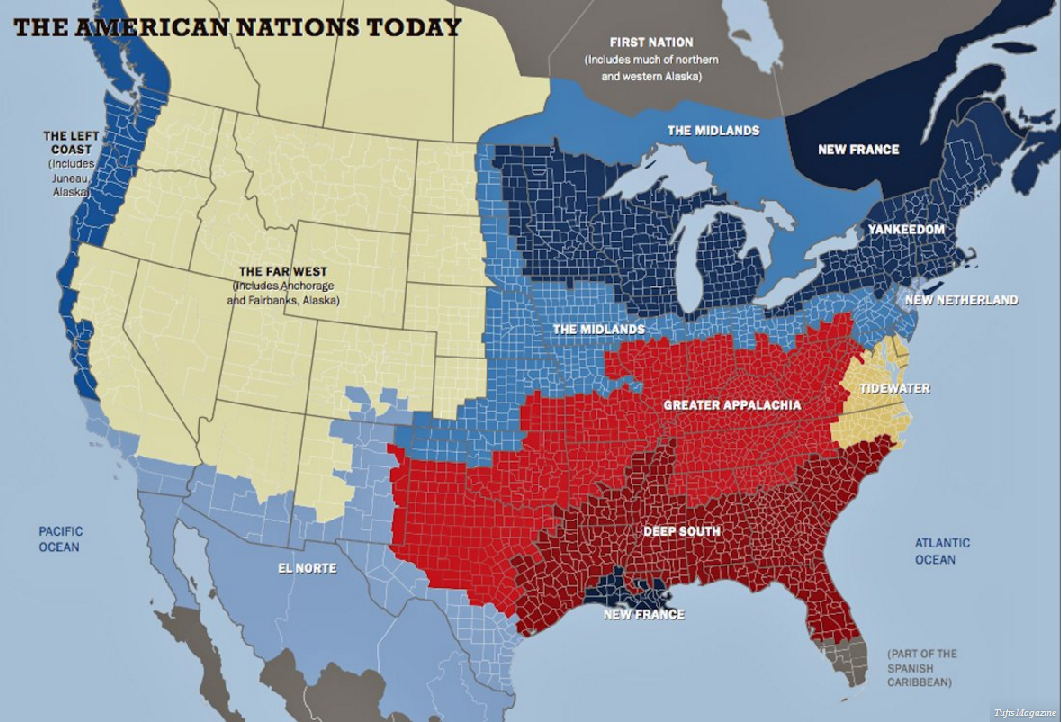

The result of those centuries of turbulence is a Sunni population where Iraq borders Turkey, Kurds in the northeast, and a Shia population where Iraq borders Iran in the south.

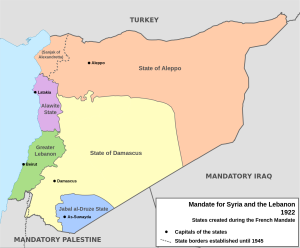

The British got control of Iraq when the Ottoman Empire fell and established a Sunni government with a king from French Syria. Iraq gained independence in 1932. In 1941, Britain invaded to protect oil supplies following a military coup and reestablished the monarchy. There was another military coup in 1958, and that regime was overthrown by the Ba’ath Party in 1968.

The Iraqi Ba’ath Party formed in 1951/2 was Arab Nationalist, socialist, and primarily Shia but it slowly became Sunni and dominated by the military. When General Saddam Hussein gained control in 1979, he welcomed the fall of Iran’s Shah, but Ayatollah Khomeini, wanting the Islamic Revolution to spread, armed Shiite and Kurdish rebels in Iraq, so in 1980 Iraq declared war. After some initial success, its forces were driven out in 1982 and for the next six years, Iran was on the offensive. The war ended in stalemate with half a million to 1.5 million dead.

The US had broken with Iran when the Shah fell and supported Iraq in the 1980-1988 war, but when Iraq invaded Kuwait in 1990, US-led forces quickly drove them out. The Iraq/Kuwait border had been fixed by the British in 1913 and accepted at first by independent Iraq but it was disputed since the 1960s. In 2003, claiming that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, the US reversed course and led an invasion. Saddam Hussein’s government was replaced by a Shia-led one that excluded many former officials and disbanded the mainly Sunni army, then chaos and intense violence ensued between Sunnis and Shias.

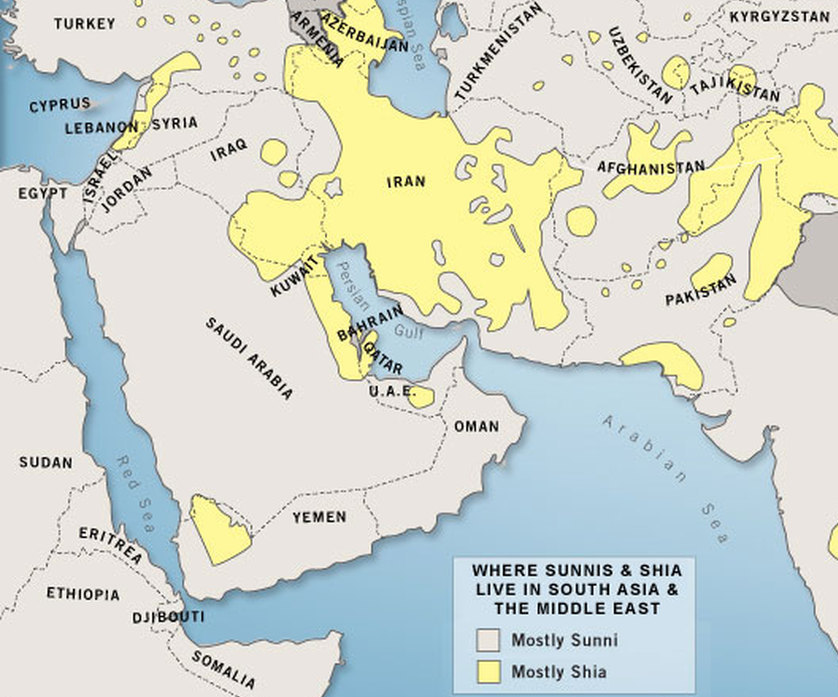

US leaders assumed a Shia government would be pro-American because Saddam Hussein had oppressed Iraq’s Shias. Instead, it cautiously allied with Shia Iran, which the US, Saudi Arabia and Israel saw as a great threat. VP Cheney warned of “a nuclear-armed Iran, astride the world’s supply of oil, able to affect adversely the global economy, prepared to use terrorist organizations and/or their nuclear weapons to threaten their neighbors and others around the world.” Jordan’s King Abdullah warned of an Iranian-led imaginary crescent that would stretch from Qatar, Bahrain and Kuwait through Iran to Syria and Lebanon.

Those fears were fanciful. There is much more in common between Sunni and Shia Iraqis than between Iraqi and Iranian Shia. Iraq’s Shias are chiefly Arab while only 2% of Iranians are Arab, the majority being Persian (60%+) while those in the north are mostly of Turkish heritage (20%+) and Kurds (10%). The conflict between Sunni and Shia in Iraq is chiefly about the right to rule. It results from the Shias’ long suppression by Sunni governments in Baghdad.

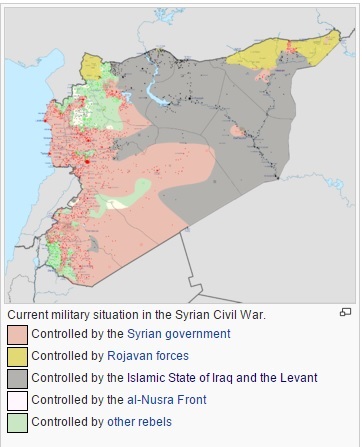

Now Iraq’s leader since last September is trying to build trust with the Kurds and Sunnis who were alienated by his divisive Shia predecessor. His view of Iran and Iraq’s strategic imperatives is clear. He says he will “take any assistance, even from Iran” against the Islamic State that, in the aftermath of our destruction, now controls large parts of Iraq. Iran began providing direct military aid to Iraq in mid-2014 and an Iranian General now appears to be commanding both Iraqi and Iranian forces against the Islamic State.

So… Our government at this time finds itself supporting Iraq’s Shia government, increasingly less committed to overthrowing the Shia regime in Syria as its Sunni Arab allies want, and seeking to end its estrangement from Iran.

Confusing as that is, it is good to stop escalating bloodshed by arming adversaries whose allegiances keep changing. I will explore what to do about the Islamic State in a future post.

The chaos in Iraq now is very far from new. Its future will continue to be determined by its position between powerful rivals, and whether it can establish an effective government for all Iraqis.