What components must a tax and budget management system have to achieve the results we want? I’ll start with a result and a candidate that illustrate a few large issues.

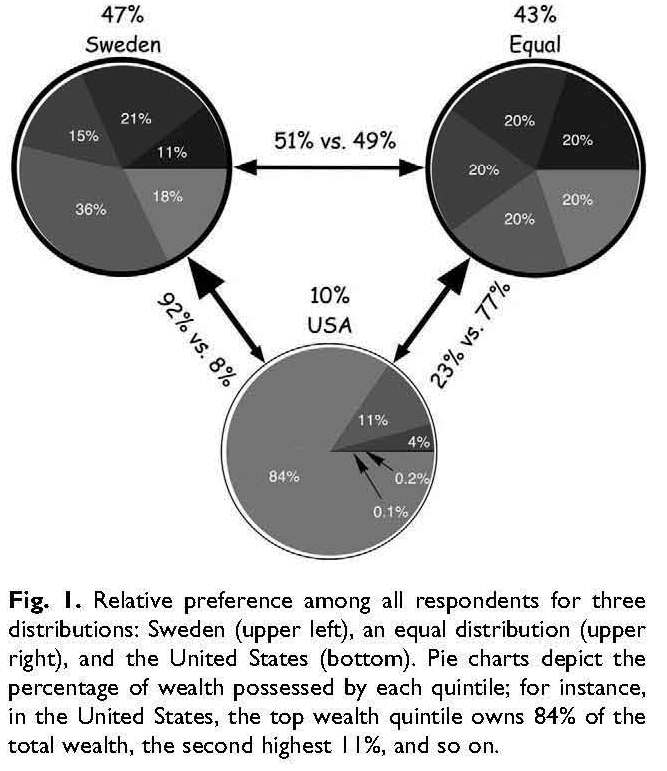

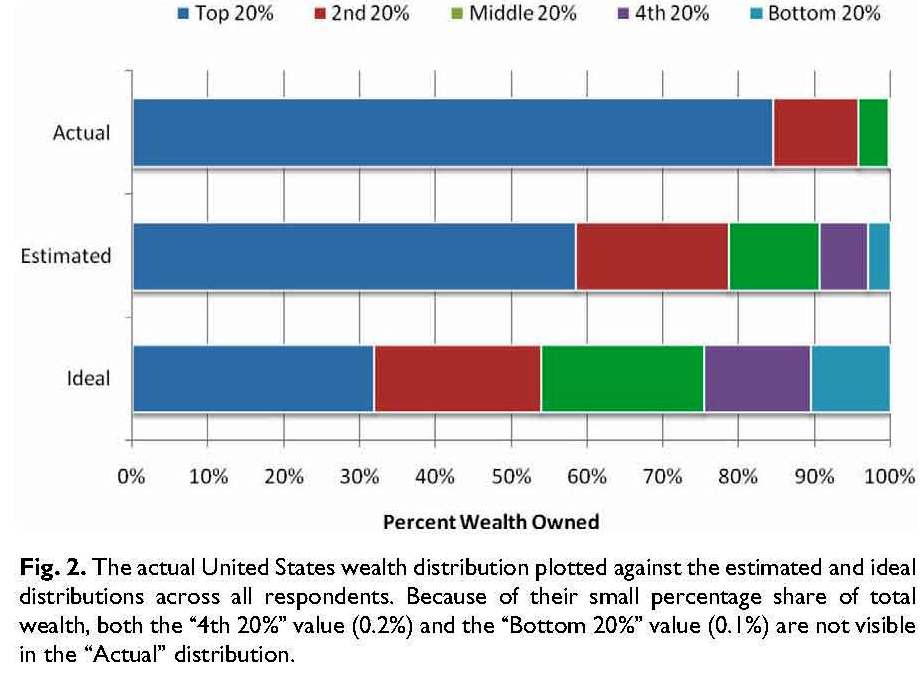

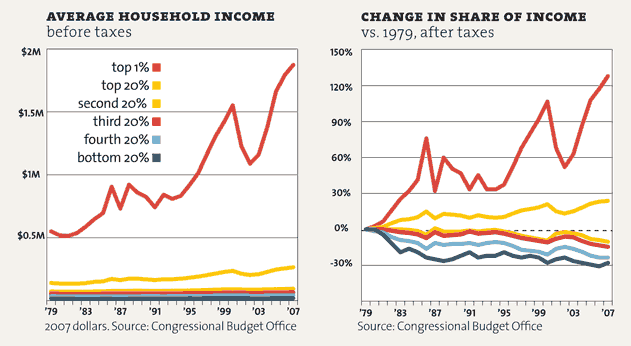

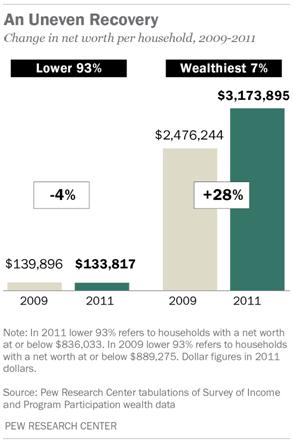

It seems to me now that what I said was my biggest surprise in this post, Qualities of an Excellent Tax System, should not have been a surprise at all. The American Dream is that our freedom includes equal opportunities for all of us to achieve prosperity and success. In that case, it makes sense that nine out of ten of us would say we want a relatively equal distribution of wealth. What we mean is, we want relatively equal opportunities to become wealthy.

So, the system needs to to, “lead toward the distribution of wealth we democratically choose”. By “lead toward” I mean propel the wealth distribution on average and over time, and by “democratically choose” I mean the distribution we want could change but it should at all times be in some way explicitly approved by the electorate.

Among the indicated requirements is to diminish, “unfair opportunity based on parental wealth”. Estate taxes are a potential mechanism. How much support might there be for them, and how effectively would they support the objective?

Estate taxes would not be popular at all. The compendium of public opinion research I used for this post about our tax system shows on page 21 the results of a March 2009 Harris poll about the perceived fairness of various kinds of federal and state/local taxes. Federal estate taxes are considered the least fair of all. Two in five respondents (42%) consider them “not at all fair”. Fully two thirds (67%) consider them “somewhat or not at all fair”.

Before exploring if estate taxes could nevertheless be effective, it’s instructive to set their unpopularity in context. Every form of tax has high “somewhat or not at all fair” ratings.

At the federal level, the combined “somewhat or not at all fair” ratings for each type of tax are: estate taxes 67%, gas taxes 63%, personal income taxes 48%, corporate income taxes 42%, social security payroll taxes 40%, and cigarette, beer and wine taxes 36%. At the state/local level they are: gas taxes 62%, local property taxes 50%, motor vehicle taxes 47%, state income taxes 44%, cigarette, beer and wine taxes 38%, and retail sales taxes 37%.

I’ll come back to those statistics in future posts. One thing to consider is the seeming paradox that while gas taxes are almost as unpopular as estate taxes, retail sales taxes, which are also levied at point of sale and unlike gas taxes are shown separately and so are more visible, are considered the least unfair of taxes along with those on cigarettes, beer and wine. I’ll also address why property and motor vehicle taxes, personal and corporate income taxes, and social security payroll taxes are all considered “somewhat or not at all fair” by 40% to 50% of us. The overall message from these statistics is:

Large issue 1: While everyone wants government services, many or most of us consider every way of funding them to be “somewhat or not at all fair”. It will not be enough to establish a way of collecting revenue that is reasonably fair. We must also routinely measure its fairness, publish the results and measure public opinion about that. The long term result, if the system truly is fair, will be a steep bell curve of survey results toward the middle of the range from “Very fair” to “Not at all fair”. I’ll explore this in a future post.

Meanwhile, why are estate taxes considered most unfair of all? Because they’re associated with death. That’s why opponents call them the “death tax”. We’re pretty much terrified of death and we don’t like any taxes, anyway. Also, opponents tell us it’s double taxation: “First, they took your hard-earned money in income tax, then they want estate taxes on what’s left?!” And while in theory we want equal opportunity for all to become wealthy, we probably in reality want our kids to have a better than equal chance. The message from this statistic is:

Large issue 2: We are vulnerable to powerful fears and desires that distort our judgment about government and taxes which cannot be soothed from within the tax system. We would be happier and kinder if we accepted that we will die. It would be better to prepare our kids to work for what they most want. The tax system is powerless to help us accept and act upon such truths.

Would estate taxes nonetheless be an effective way to diminish the unfair advantage of parental wealth? The answer is again, in normal circumstances, no. Estate taxes are in reality levied on only a tiny fraction of US estates and they are easy to avoid altogether with trusts and provisions in your will. If, that is, you act on the fact that you will die.

More importantly, revenue from estate taxes fluctuates because people with equal wealth do not die at the same rate every year. That means estate taxes are unsuitable for supporting ongoing levels of spending. There is also:

Large issue 3: Wealthy people can relocate their assets. Not all US states levy estate or inheritance taxes and those that do, have different rates and thresholds. You can become a resident of a different state if you expect to leave or inherit a large estate. The same issue exists for state income taxes as this link suggests. And if you want to avoid US taxes altogether, you can renounce your citizenship and move offshore. This means tax systems must be appropriate to their competitive environment, state-wise and nation-wise.

There are, however, a couple of situations where estate taxes are effective. One is when there is a widely accepted temporary need for exceptionally high government spending. By the end of WW2, for example, the top marginal estate-tax rate, referred to as “equality of sacrifice”, was 75% in the UK and 77% in the US. In WW1 when UK men were being conscripted, very high estate taxes were termed “conscription of wealth”. The other situation is when the domination of a wealthy hereditary aristocracy is overturned. The sacrifice made necessary by WW1 gave UK social reformers that opportunity.

We should work diligently and hard to avoid the need and opportunity for such a remedy in our own society.