Saddened when I went trekking by all the hardships I saw, I thought: “I know how to devise strategies, what’s a good one for Nepal?” It was only after many more trips that I saw the root of the problem.

It is easy to see a good strategy for Nepal. It has over 80,000 MW of hydro-power potential, much of which it could export, and its near neighbor, Bhutan, has made good deals with India to do exactly that.

But Nepal has failed to make such deals and has developed less than 1% of its potential.

Why the difference? Corruption. Corruption is when someone uses a position of authority for their personal gain.

But the whole point of having a position of authority throughout Nepal’s history was personal gain.

And that motivation has not changed — see Electricity and Corruption.

Nepal never had what we understand by “government”. Its administration never was intended to provide services to the people. It existed to operate a tax farming business owned by Hindu kings and run by a high caste Hindu family.

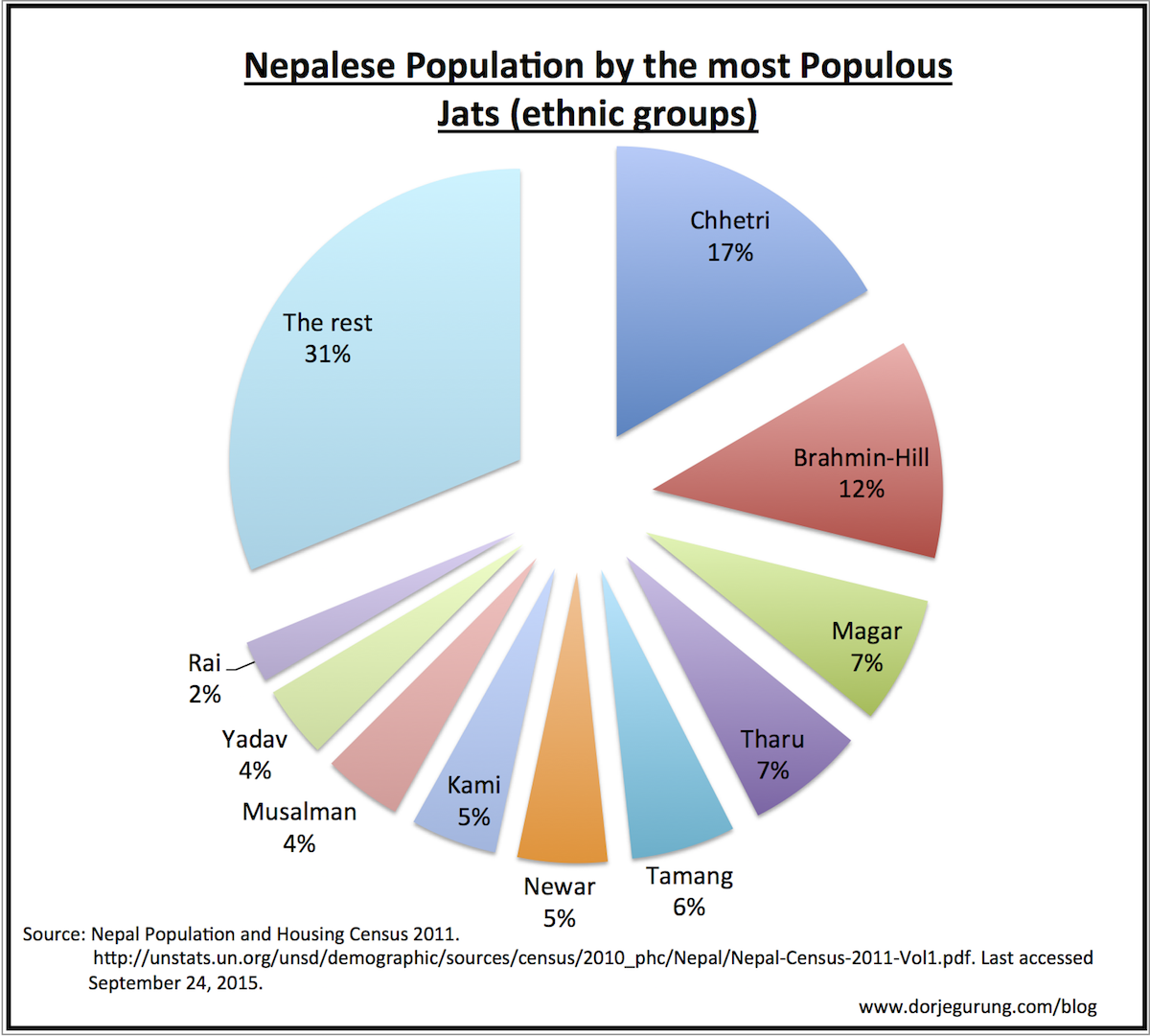

That ruling elite was a tiny minority within the high caste groups that make up less than a third of Nepal’s diverse population where over a hundred mutually unintelligible languages are spoken.

As these charts from a good article on the topic illustrate, Chhetri and Hill-Brahmin people make up 29% of the 28 million population. Doma’s Tamang people are one of the larger non-Hindu tribal groups.

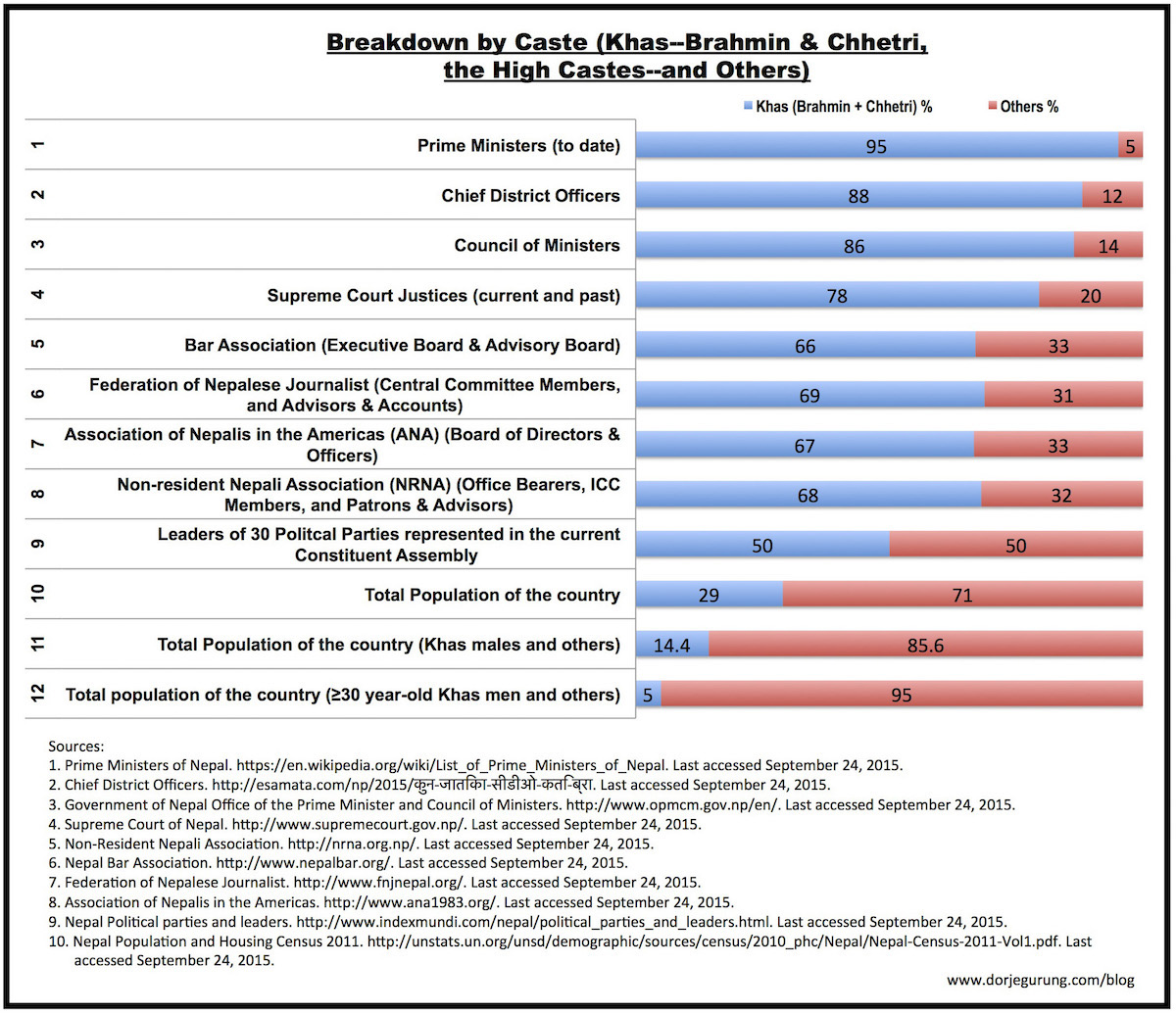

Since Nepal was owned and operated by high caste Hindus for 240 years and the Hindu monarchy fell only seven years ago it is no surprise that the government is still dominated by high caste Hindus.

Nor is it surprising, given the enormous over-representation of high caste men in the government, judiciary, journalism and other positions of influence, that they would have engineered the new Constitution to maintain their privileged position.

Voting in Nepal is along ethnic lines unless that’s trumped by who pays most for your vote. Brahmin and Chettri subsistence farmers who live in the hills will vote for wealthy Brahmin and Chettri politicians simply because of their caste.

That is why the electoral districts defined in the new Constitution were jerrymandered to include a sufficient number of hill people.

Can this culture of “corruption” that makes it impossible for Nepalis to have “government” be changed?

When the new Constitution was announced, Dr. Baburam Bhatterai, Prime Minister from August 2011 to March 2013, split from the Maoist Party that had led the monarchy’s overthrow. He is forming a new party. To replace exploitation with government, he says, it is necessary to start anew.

Baburam’s leadership will have some effect but much more will be necessary, and while legislation can sometimes be enacted quickly, cultures only ever change slowly.

Nepal’s politics-for-profit culture will not be changed by those it benefits. I’m hoping the protests by the Madhesi that make life even harder for all but the privileged few will turn out to have been the equivalent of our civil rights protests half a century ago.