We the people whose Constitution “promote[s] the general Welfare, and secure[s] the Blessings of Liberty” are easily confused. We have the habit of trusting ideas about what things are and how they work.

We must trust our ideas in everyday life: we’d be paralyzed if we always had to figure everything out from scratch. But we trust too far. We tend not to notice facts that conflict with our ideas.

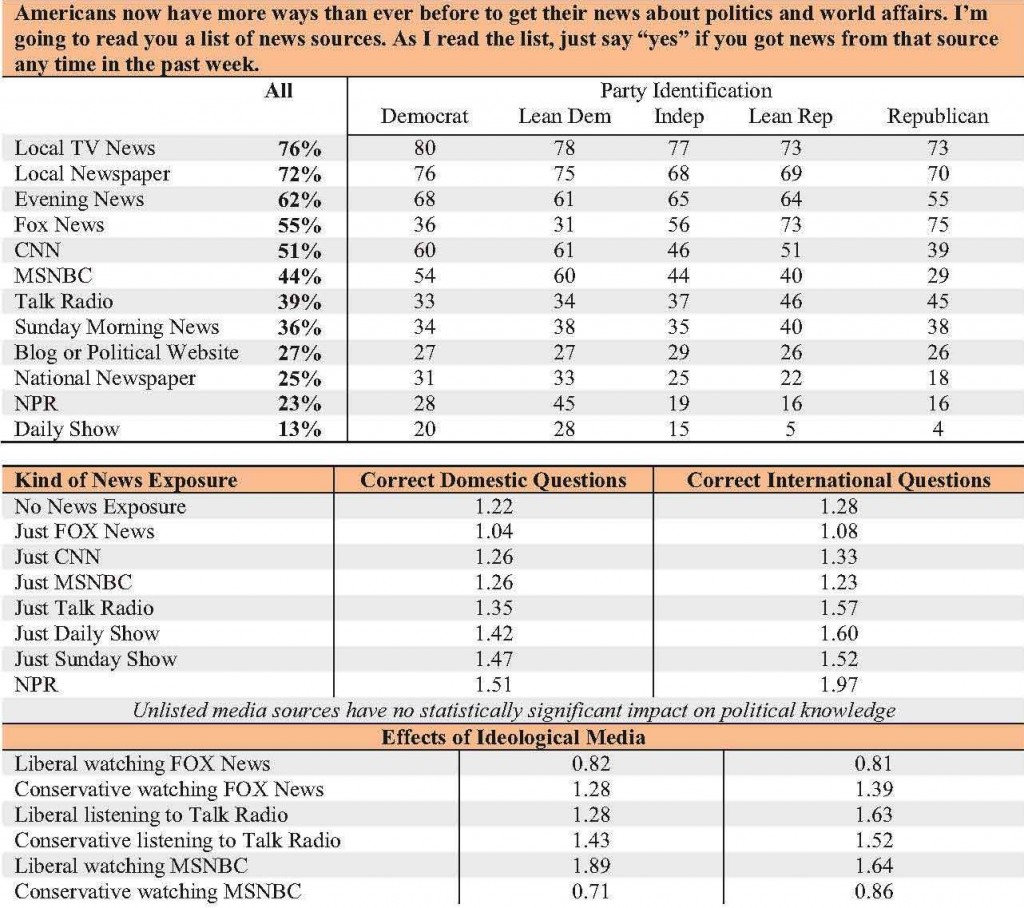

Fairleigh Dickinson University recently surveyed 1,185 respondents on which news sources they used and what facts they knew about current events. The results are quite distressing.

On average, respondents correctly answered only 1.8 of 4 questions about international news, and 1.6 of 5 questions about domestic affairs. On average, we don’t know or are wrong about more than half the facts of what’s going on. Why?

Because news media do not aim to provide facts but entertaining opinions, especially about the stupidity of those with other opinions.

Media coverage of the survey was more eye-catching than analytical. Left-leaning commentators trumpeted that those who watch FOX News got only 1.04 correct answers to domestic questions while those with no exposure at all to the news got 1.22, and they got only 1.08 correct answers to international questions while those with no news exposure got 1.28.

But do these survey results mean watching FOX News makes you more ignorant? Do they mean watching MSNBC leaves you as ignorant as those who follow no news media? Not exactly.

What the survey demonstrates, since liberals watching FOX News and conservatives watching MSNBC are much less likely to know the facts than those who follow no news media, is that our opinions, our preconceptions, our ideas lead us to ignore the facts.

Facts presented on FOX News are much less likely to be noticed by liberals. Facts presented on MSNBC are much less likely to be noticed by conservatives.

How can we have a good future if the average American doesn’t know or is wrong about so much of what’s going on in the world? We’ll vote for candidates who also don’t know or who lie about what’s going on and we’ll support the wrong policies.

What to do? Why do news media leave us as ignorant as we would be without them, or more so? Well, since most of their revenue comes from advertisers, they must provide what advertisers want – people motivated to buy things – and since buying is motivated not by facts but by stimulating emotions, the media stimulates emotions and anesthetizes intellects that might say, “do I really need that?”

However, an excitingly large 27% of “we the easily confused” now gets news from blogs or political websites. Much of that content is also entertainment, it’s true, but this is a medium where we can contribute. We cannot increase the factual content of the mainstream media but we can use blogs to disseminate facts, stimulate analysis and promote fact-based proposals for change.

And we can encourage media businesses beginning to find ways to serve those who want facts. The Tampa Bay Times’ PolitiFact project, for example, notes that my State’s Governor’s assertion that “about 47 percent of able-bodied people in the state of Maine don’t work” is of “pants-on-fire” quality.

At the start of this topic I wrote: “Honesty in the media has always been problematic but the impact of today’s big media seems more powerful than in the past.” There are now, however, so many other sources of facts and analysis along with media where I can debate what the facts suggest with folks whose preconceptions are different from mine. That is a highly encouraging development.

How many of us must work at “disseminating facts, stimulating analysis and promoting fact-based proposals” to head us in a better direction? Speculating about that is a waste of time. Society’s direction will change for the better if every individual who cares about it does the work.

This article about the most searched-for items in 2013 and the items most often shared on Twitter and Facebook confirms that we really don’t want to know the news. Here’s what we want:

“The stories and videos most likely to be shared, emailed, and posted on Facebook aren’t necessarily the newest stories, but they are the most evocative. The most famous of these studies, by University of Pennsylvania professors Jonah Berger and Katherine Milkman, concluded that online stories producing “high-arousal emotions” were more viral, whether those emotions were positive (e.g.: happiness and awe) or negative (e.g.: anger or anxiety).”