Because we tax the income of legal entities, i.e., corporations, not just people, this post extends the exploration of who we tax. Corporations are not the only form of business enterprise so it examines our overall business tax system. It does not, however, address who ultimately pays business taxes; the customers who unknowingly pay a higher price, owners who unknowingly provide additional capital and/or, other academics say, employees.

Personal income tax is on gross income but corporate is on net, i.e., profits. In other words, while most costs of earning a wage are taxed, most of a corporation’s costs are not. Both income taxes have lower rates for lower amounts of income, and both are levied by states and the federal government. Federal rates start at 15% for the first $50K of corporate income, which is more than the total income for over 90% of US corporations. States levy at an effective rate in the range of 2% to 5%.

In an increasingly competitive global economy, how do our business taxes compare to other nations? Our top corporate tax rate, federal plus state and local, is among the world’s highest but that is not necessarily what businesses pay. GE, for example, our 6th largest business by revenue and 14th most profitable, paid no tax at all in 2010. The rate US businesses actually pay is where it starts to get complicated.

There are many ways to compute effective business tax rates, i.e., what businesses actually pay. “Effective 1” in the table below from the US Treasury calculates it as corporate taxes versus corporate operating surplus. Using that formula, we are at 13%, which is lower than the 16% average for OECD nations and almost the same as Canada. The formula used by the equally authoritative World Bank, however, “Effective 2”, places us highest at 28%, almost double the OECD average and four times as high as Canada and France. The formula used by a source with a tax reduction agenda, which gives the rate on the highest income bracket, i.e., the “Marginal” rate, shows us at 36%, which is also twice the OECD average. Trying to figure what percentage of profits corporations pay in taxes leads to no definite conclusions.

Tax collected as a percentage of GDP is a dependable measure, however. It shows how our business tax system compares to other nations and it illuminates the trends. This measure shows the 3.4% average for all OECD nations over the years 2000-2005 was over 50% higher than our 2.2% rate. Only Germany’s was lower. And the OECD average for 2008 was almost twice as high as ours.

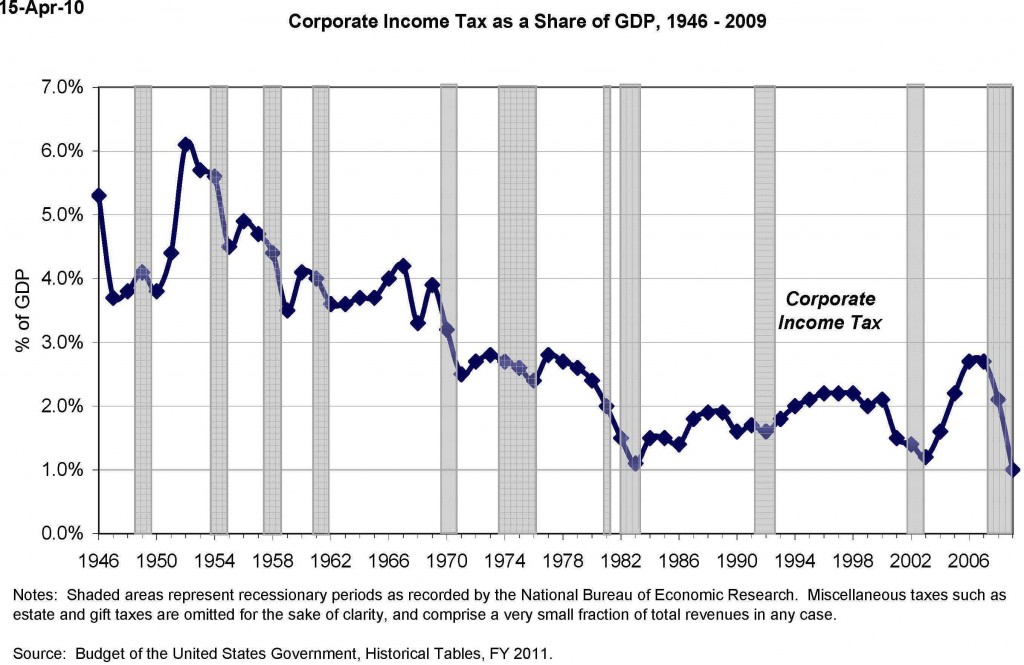

US corporate income tax as a share of GDP dropped until the early 1980s and was relatively stable in the range of 1% to 2% for the next two decades. In the most recent decade it has fluctuated more but has not yet dropped back to 1% as forecast in the chart below from the Tax Policy Center.

Why do US corporations pay such a small amount of tax? This US Treasury background paper notes that our business tax system: “includes an array of special provisions that reduce taxes for particular types of activities, industries, and businesses”. Some of those tax preferences are reviewed in what we do not tax. The report estimates that: “If the tax base were broadened by removing these special provisions, the top [federal] corporate tax rate of 35 percent could be reduced to 27 percent.”

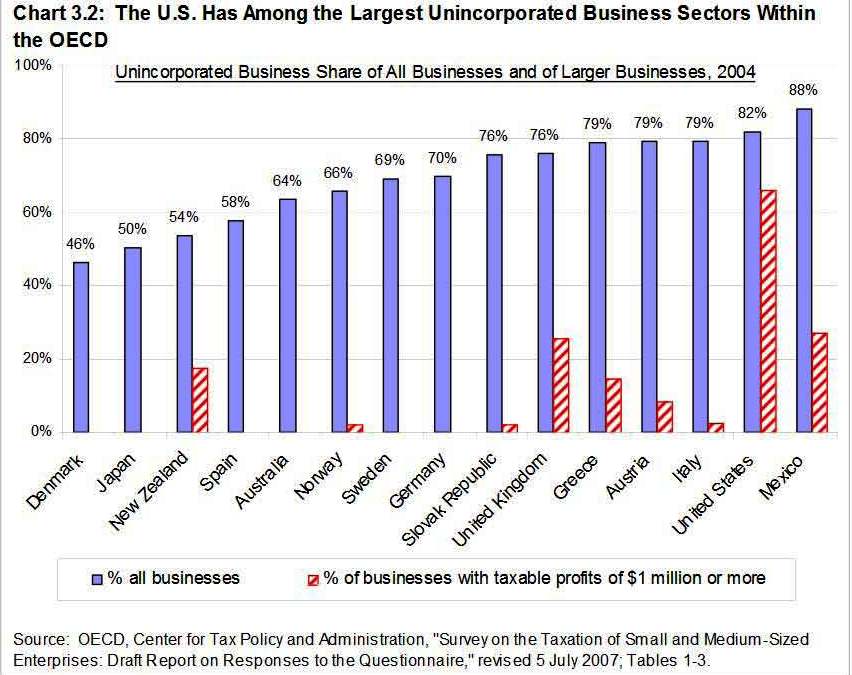

The Treasury report also points out a further complication: “A substantial share of [US] business activity and income is generated by flow-through entities not subject to the corporate income tax but instead generally taxed to individual owners” and notes that: “Although many of these 27 million businesses are small, in the aggregate they generate about one-third of business receipts and total deductions and one-third of salaries and wages … [and they] produce half of business net income”.

Two thirds of all US businesses reporting profits of $1 million or more in 2004 were not incorporated, far more than in other nations. Why? A primary reason for business owners to incorporate is to receive limited liability protection but in the US we also have S corporations, limited partnerships, and limited liability companies that offer protection. Legislation establishing S corporations introduced in 1986 applies to companies with 35 or fewer shareholders. Their income is passed through to the owners for tax purposes as in a partnership. S corporations do not pay corporate income tax.

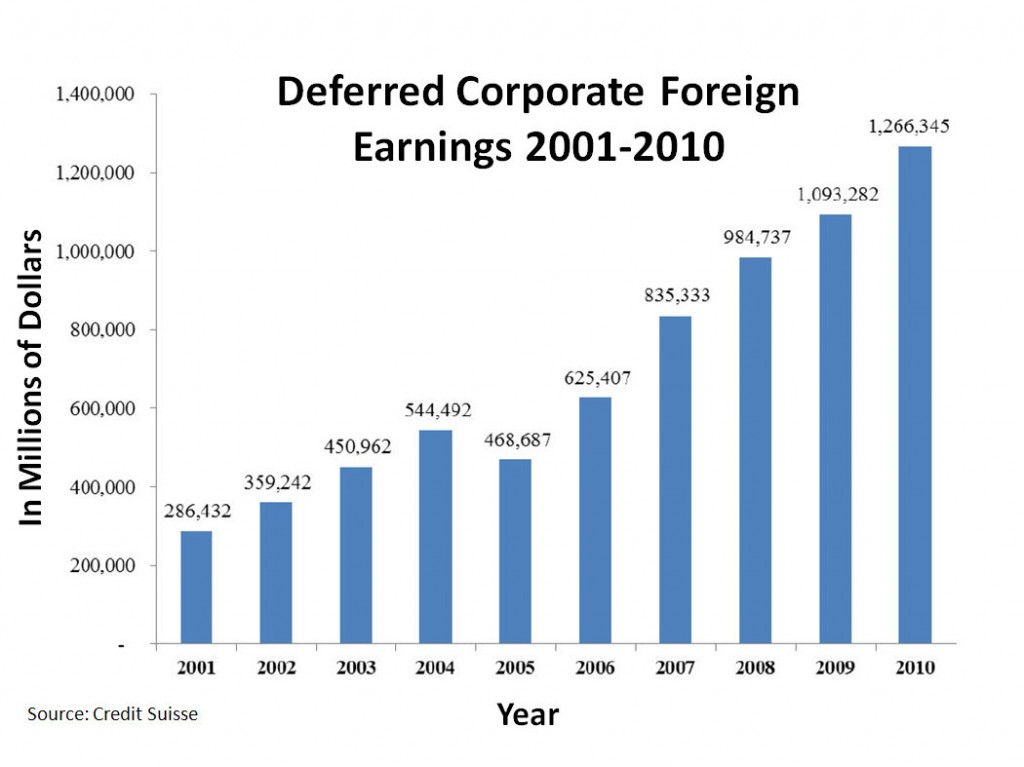

How is taxing US businesses affected by globalization? US companies only pay local taxes on foreign subsidiaries’ profits if they are returned to the US. This means they can dramatically lower their taxes by recording profits in subsidiaries in tax havens like Bermuda. Their intellectual property (IP), e.g., patents, can be owned by a subsidiary in a low tax offshore jurisdiction. Payments to the subsidiary for use of the IP by the corporation’s high-taxed US entity reduces the US entity’s profit. The artificial profits of the subsidiary are said to be deferred because they will be taxed at US rates if they are returned to the US, but in effect they have been transferred where they are not subject to US taxes.

Our business tax system greatly favors large enterprises that can take advantage of foreign subsidiary tax accounting complexities. It benefits large enterprises in many other ways, too. They have more access to debt financing, for example, and because interest expenses are treated as a cost of doing business, that cuts their taxes. It is tempting to delve deeper into how large businesses and their executives are favored but the goal of these posts is to explore not detailed mechanisms of our tax system but its overall results. The next post in this series will assess those results and how they compare to what we want. Finally, I will explore some potential changes.