In the world of finance, moral hazard exists when someone can profit from successful bets and suffer little or nothing from bad ones. In the 1980s Dukes of Hazzard show the Duke boys, their beefed-up Dodge Charger and their short-shorted cousin Daisy keep foiling corrupt county commissioner “Boss” Hogg’s scams but because the well-meaning boys often bail him out, he’s always coming up with new scams. So it has been in the world of finance for the last three decades.

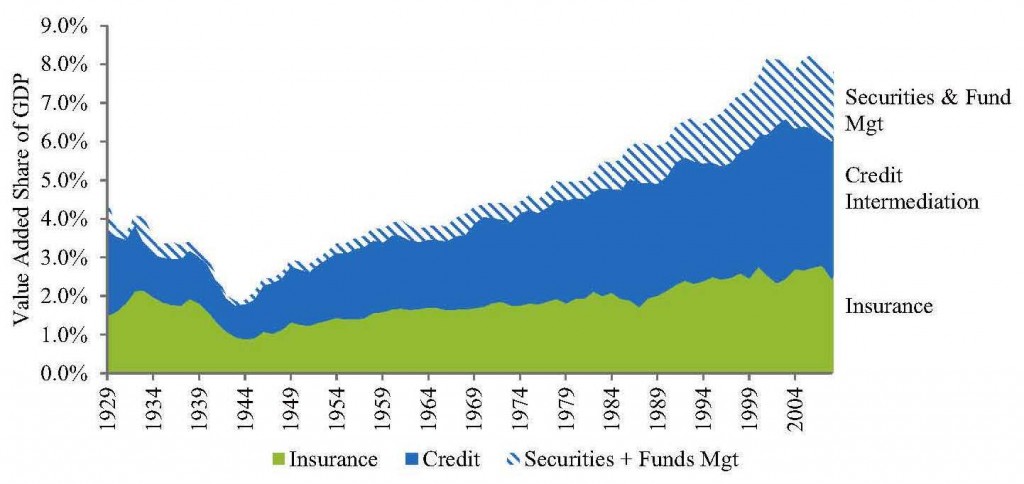

Moral hazard inflated the bubble whose collapse in 2007 left us wallowing in the Great Recession. Wall Street executives made bets that profited them immensely expecting, correctly, they would not suffer when the bubble blew. Their firm might suffer, perhaps even cease to exist, but they would keep their profits. Their firm might pay penalties for law-breaking, but they would not. Moral hazard defeats what finance should do, allocate capital where it will have most value and efficiently reallocate risk. This post examined finance’s mechanisms – securities, credit and insurance – and the following one highlighted regulatory changes enabling the mechanisms to be used in ways that led to the 2007 financial crisis. This post explores how Washington became Wall Street’s savior.

Bailouts of individual enterprises started in 1971 when defense contractor Lockheed was rescued from financial mismanagement with $250M of loan guarantees. Then in 1973, the Penn Central Railroad, which declared bankruptcy in 1970 but was considered “too big to fail”, was merged by Congress into Conrail, whose operating costs Congress spent $7B subsidizing. Next, in 1980, Chrysler was bailed out with $1.5B in loan guarantees. So, with these bailouts starting in 1971, Washington began thwarting capitalism’s creative destruction.

Lockheed was mismanaged financially, its defense and civilian mega-projects had big cost overruns and were late, and it was bribing foreign government officials. Penn Central’s executives utterly failed to gain operational control after it was formed in a 1968 merger. Chrysler’s executives produced its uncompetitive cost structure and low quality products. If, to take just one example, Chrysler had declared bankruptcy, its management would have been replaced and its contracts renegotiated. Because it was not restructured, it inevitably failed again and leaders of GM, Ford and the unions learned they, too, might expect to be bailed out.

The Chrysler bailout, the first whose rationale was to save jobs and the economy, set an especially bad precedent. In 1987, the Fed took the next step along that path of unintended consequences which led to the 2007 financial collapse. The Fed’s traditional mission had been to manage inflation and promote sustained output growth by supervising credit. Now it began trying to manage asset prices.

When the Dow plunged 23% on October 19, 1987 following drops of 4% and 5% the previous week, the Fed promised before the market opened the next day to “serve as a source of liquidity to support the financial and economic system”. No economic event had triggered the crash. Stock prices had simply risen too far too fast, 40% in the first eight months of the year, and there was panic at the first sign of the bubble deflating.

Why, then, did the Fed do anything? Because Fed Chairman Greenspan saw market prices not as an indicator of the economy’s health but as something he should manage.

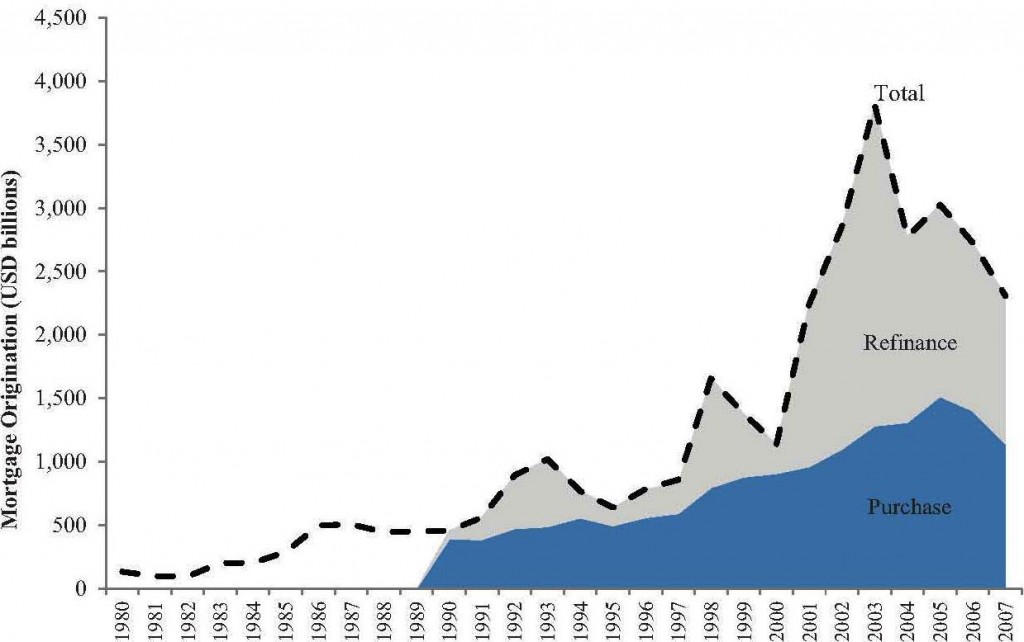

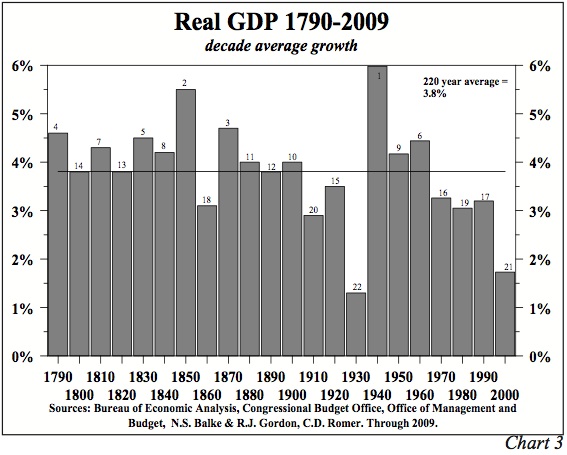

Market prices kept heading up through the 1990s following each downward blip, e.g., the LTCM hedge fund collapse and bailout in 1998, until in 2000 the dotcom bubble collapsed. Greenspan then began cutting interest rates almost month to month from 6% in January 2001 to 1.75% by year-end, and he kept on down to 1% in 2003. Consumer spending, around 70% of the entire US economy, had barely dropped; only the stock market had plunged. Greenspan’s unprecedented rate-cutting was not required to stimulate economic growth but stock prices, which it did until the next collapse.

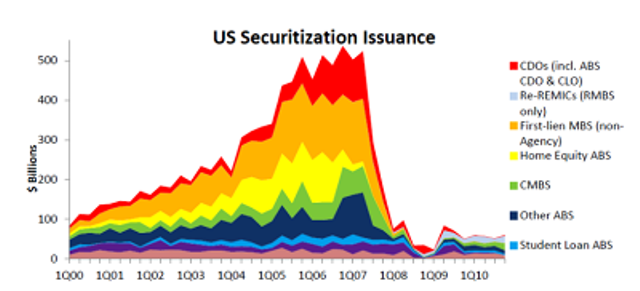

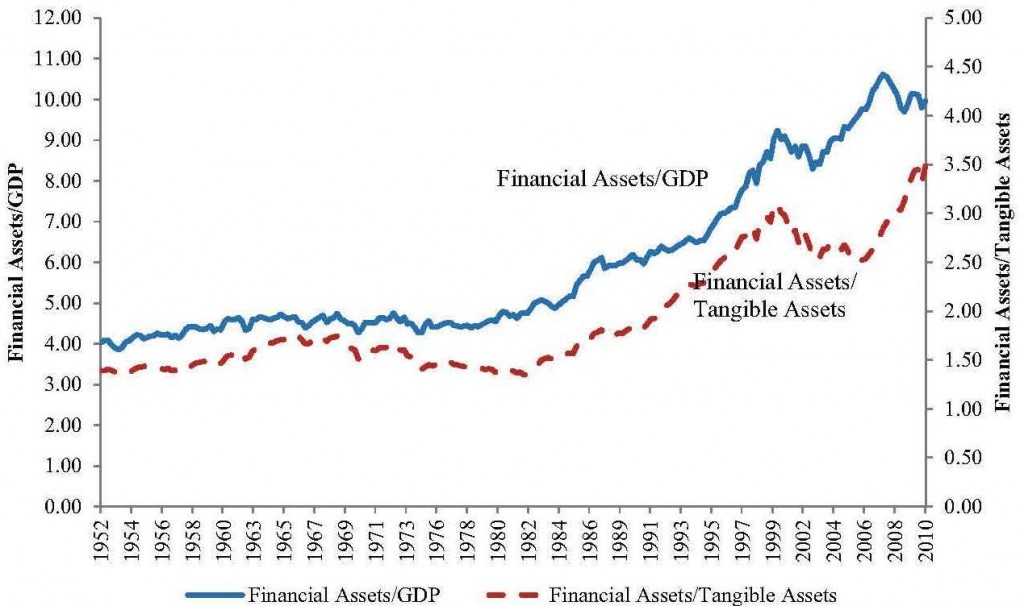

Interest from investment was now so low that it became essential to speculate for income – trust funds and foundations must disperse 5% of assets each year. And speculation seemed safe because a new pattern had emerged; when bubbles collapsed, the Fed would save the day. So houses, traditionally a safe investment, became a vehicle for speculation. Until that bubble collapsed in 2007.

The Fed was not the only creator of moral hazard. Congress, in the 1995 Securities Litigation Reform Act to control nuisance class action lawsuits, exempted accountants from liability for fraud by their clients. Accounting scandals soon followed. Enron was the most dramatic and its 2001 fall also took down its auditor, Arthur Andersen, one of the “Big Five” accounting firms.

The SEC’s contribution to the 2007 crisis was facilitation of stupidity. From 1975, the SEC limited investment bank borrowing to no more than $12 on each $1 of their capital. In 2004 they gave the five biggest ones a special exemption that allowed them to lever as much as 40:1. Three years later, all five of them were insolvent. First, Bear Stearns went belly-up in a bank run when clients fearing it was over-leveraged pulled out 90% of its liquidity in two days. Almost immediately after that Lehman Brothers became the largest bankruptcy ever in the USA.

Bear was eased into the arms of JP Morgan with $29B of guarantees from Washington. Lehman was allowed to fail. Its clean assets were bought by Barclays and others. But then Washington stepped in full force. Merrill Lynch was helped to sell itself to Bank of America. Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs borrowed massively from Washington and changed their status to commercial banks so Washington would lend them more. The Fed bailed out AIG whose massive exposure to derivatives made it “too big to fail” and Secretary of the Treasury Paulson, ex-CEO of Goldman Sachs, nationalized Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac for the same reason.

Why were these economy-threatening institutions allowed to grow so big? Deregulation of the barriers was strongly advocated throughout the 1990s by Treasury Secretary Rubin, formerly co-chairman of Goldman Sachs.

And why were economy-threatening derivatives not regulated? Rubin’s advice was instrumental in that decision, too. He later became a director and temporary chairman of Citigroup.

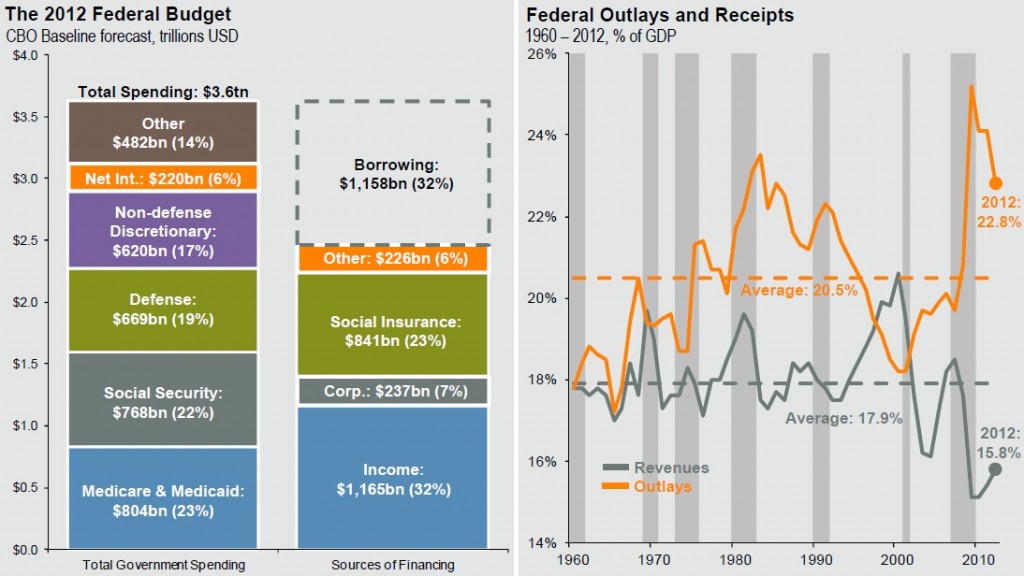

When asset prices tumbled as the real estate bubble collapsed, banks had to stop lending, not that there was much demand for new borrowing. It was said to be a liquidity crisis because the big banks were, or were close to being, insolvent. The confusion led to a Wall Street crash. In that panic, Treasury Secretary Paulson proposed a $700B program to inject capital into the big banks and buy the junk off their books while the Fed began far more massive capital injections via all the big banks.

Pretty soon Washington (the Fed, FDIC, Treasury and FHA) had a $15T commitment of monies spent, lent, and guaranteed, around the size of the entire US economy. Much of what was lent has since been repaid because the big banks were saved and many of the guaranteed loans were sound. Nonetheless, the cost looks likely to end up in the range of $1.5T to $3T. Those numbers are too large to imagine. For comparison purposes, the inflation adjusted cost of WW2 was around $3.5T.

And saving the banks but did not avert global economic recession. Furthermore, the saved big banks are still too large to fail and their executives are still profiting as they did before when, for example, the CEO of Citibank was paid $130M from 2003 until late 2007 when Citi’s stock collapsed from 55 to 2.

I’ll explore in the next post why the people who wreaked such destruction on their employers got to keep their enormous rewards and why although their employers later had to pay big penalties for fraudulent actions on their watch, none of the executives has been indicted.