Congress asked the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to assess the cost of the 2007 financial crisis and if the 2010 Dodd-Frank legislation will prevent future crises. GAO just released their findings: “the present value of cumulative output losses could exceed $13 trillion” and “[there is] no clear consensus on the extent to which, if at all, the Dodd-Frank Act will help reduce the probability or severity of a future crisis”. $13 trillion? If at all? That’s alarming.

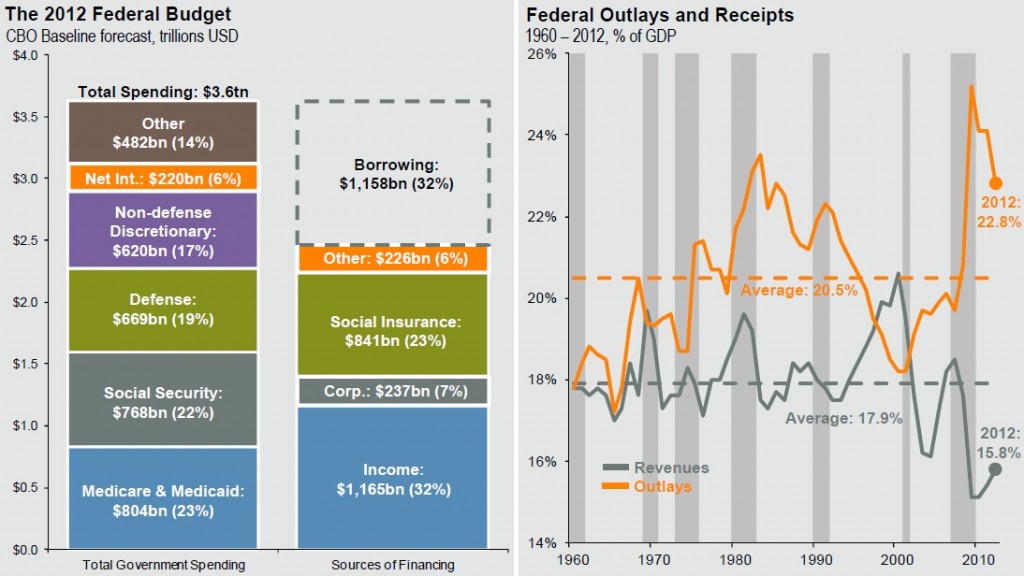

GAO studied not just the bailout cost, which looks to be $1.5T to $3T, but the overall cost. “While the structural imbalance between spending and revenue paths in the federal budget predated the financial crisis … From the end of 2007 to the end of 2010, federal debt held by the public increased from roughly 36 percent of GDP to roughly 62 percent. Key factors … included (1) reduced tax revenues … (2) increased spending on unemployment insurance … (3) fiscal stimulus programs … (4) increased government assistance to stabilize financial institutions and markets.” 36% to 62% is one big jump.

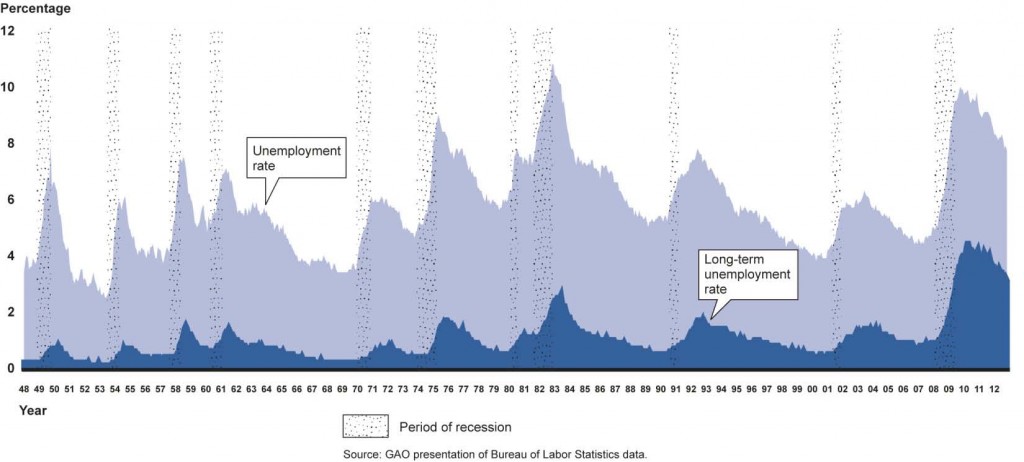

Consumer spending (70% of our economy) fell, GAO notes, because: “median household net worth fell by $49,100 per family, or by nearly 39 percent, between 2007 and 2010”. They also show the high human cost of long-term unemployment from the financial sector’s collapse.

Maybe later I’ll explore why Congress passed legislation GAO found may or may not “reduce the probability or severity of a future crisis“, legislation that is both enormously too complex and not what we normally think of as regulation. The Glass-Steagall Act that transformed finance after the 1929 Wall Street Crash has 37 pages. Dodd-Frank has 848 and does not specify rules people must follow but new regulations bureaucrats must create along with enforcement agencies. That’s not how we do things where I’d like to come from.

Maybe later I’ll explore why Congress passed legislation GAO found may or may not “reduce the probability or severity of a future crisis“, legislation that is both enormously too complex and not what we normally think of as regulation. The Glass-Steagall Act that transformed finance after the 1929 Wall Street Crash has 37 pages. Dodd-Frank has 848 and does not specify rules people must follow but new regulations bureaucrats must create along with enforcement agencies. That’s not how we do things where I’d like to come from.

The immediate, urgent question is, what must we make Congress do instead? Now I understand the problem (see previous pasts), the solution looks pretty straightforward:

- Eliminate too-big-to-fail. The collapse of the big banks and AIG threatened to paralyze our entire economy. They were bailed out because they were considered too big to be allowed to fail. Businesses that go wrong should fail. And they should fail without damaging the economy. This means banks must be limited to a maximum of, say, 5% of total US deposits and any that become insolvent must be forced into receivership under the FDIC.

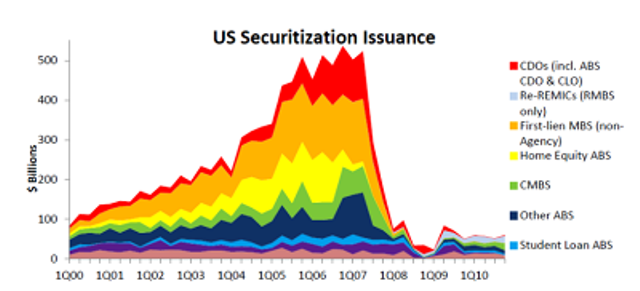

- Regulate derivatives. The collapse of any one financial institution could trigger the collapse of the whole system because inter-dependencies via derivatives were gigantic and invisible to regulators. To make them visible, derivatives must be traded on exchanges like stocks and futures, and ones that could require a future payout must be treated like insurance with their underwriters required to carry reserves.

- Restore 12:1 leverage. The big banks failed so fast because their capital reserves were too low. Our economy depends on lending and they had to stop when they became insolvent. The SEC waiver of the 1975 net capitalization rule must be reversed and SEC discretion over the rule must be eliminated.

- Restore Glass-Steagall. Tax-payers have to foot the cost of the mega-banks’ mismanagement because speculation and underwriting is no longer separate from taxpayer-backed depository banks. The separation must be restored.

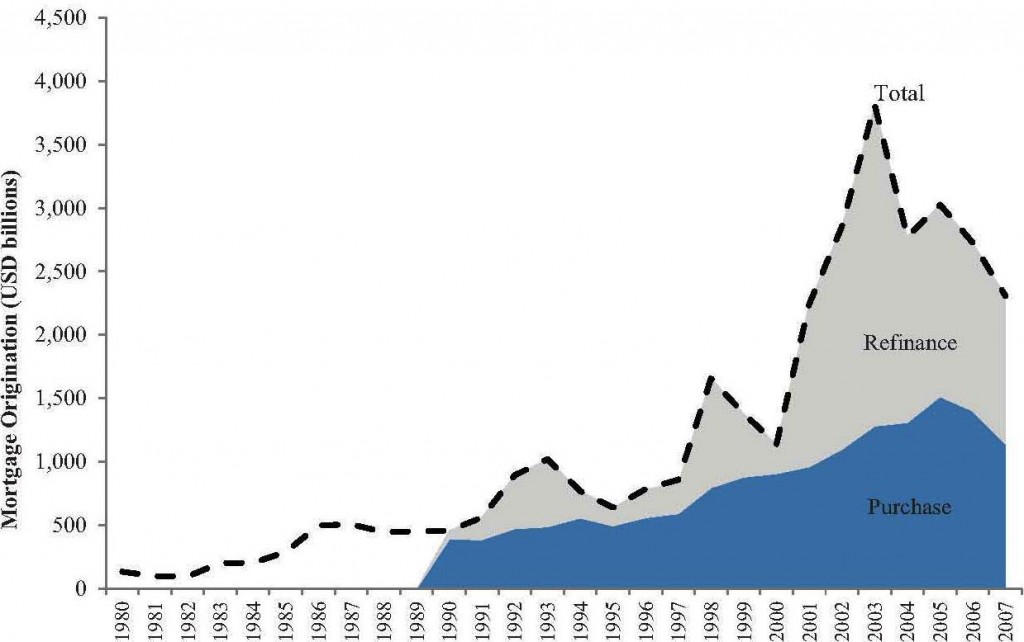

- Regulate non-bank lenders. Many of the loans most likely to default were originated by non-banks who securitized and sold them. Any institution that originates a loan must be required to keep, say, 10% of its securitized loans and absorb the first 10% of default losses incurred by investors in the securitized loans.

Among other things, the Dodd-Frank Act mandates the SEC to require US public companies to repossess executives’ short-term profits that result in long-term liabilities that require an accounting restatement. There is also discussion of ways to make senior management personally liable in the event of a taxpayer bailout. I have little confidence in either approach. Compensation committees will indemnify executives from such provisions. Shareholders and taxpayers will continue to pay.

The Justice Department recently sued S&P for up to $5B for defrauding investors with inflated credit ratings. I assume Moody’s will also be sued because they, too,were paid for ratings by investment banks that issued mortgage securities. We might hope S&P and Moody’s will change the way they do business to eliminate the conflict of interest. More proactive would be to open the ratings business to competition.

Hmm, my Buddhist practice must be helping – I got through exploring all this Washington/Wall Street malarkey without feeling angry. I feel wrathful determination to do whatever I can to get it fixed, but wrath can be positive.

Fixing the negatives will discourage allocation of capital where it will have little or no value. Next I’ll turn to the positive and explore what could guide good allocation.