Muslims split into two camps, Sunni and Shia, soon after Muhammad died in 632, they have battled ever since, and their violence has spread here. Is that true? Should we be afraid?

The Sunni-Shia divide over the succession to Muhammad obscures both what all Muslims accept and significant differences between five Sunni and three Shia schools of law as well as many schools of theology, some of which are accepted by both Sunni and Shia sects.

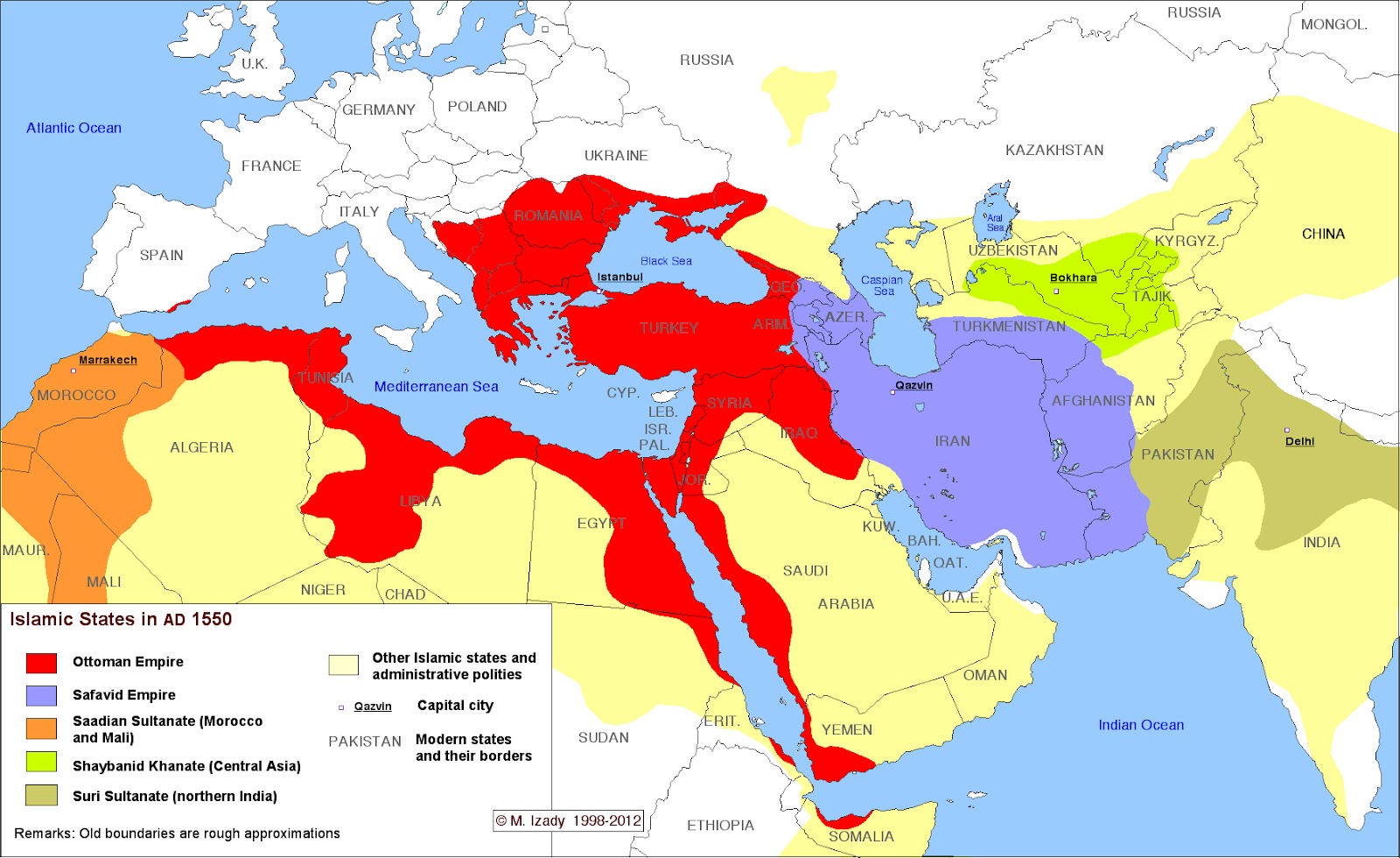

The seed that grew into today’s conflict was sown in the early 1500s when the Safavids, a Kurdish Sufi mystic order that turned militant, gained control of Iran and established a Shia sect as their empire’s religion to differentiate it from the previous regime, the Sunni Ottoman Empire based in Turkey (see this excellent article for a comprehensive geographic history of the Islamic states.)

Today’s battles do reflect sectarian differences but they are primarily about worldly power. I’ll say more about those differences and what every Muslim accepts, then review events in the recent past that made the early 1500s split newly relevant.

The Quran, Allah’s words to Muhammad, is the foundation for all Muslims. There are also Hadiths, reports on Muhammad’s words and actions that correspond to the gospels about Christ’s words and actions. Some Hadiths are followed by both Sunni and Shia, others only by one or the other. The major Hadiths happen to have been collected by a Persian Muslim.

The Hadith of Gabriel is the most important and is accepted by both Sunni and Shia. It includes the mandatory Five Pillars for all Muslims — faith in Allah and Muhammad, five daily prayers performed in a prescribed way, charity (because all things belong to God), fasting (to purify worldly desire), and pilgrimage to Mecca.

The mode of prayer is essentially the same for all Muslims and although the prayer leader in any mosque belongs to one of the Sunni or Shia schools, unlike Catholic or Protestant churches where the fundamentals of practice are different, Muslims of any school can pray in any mosque.

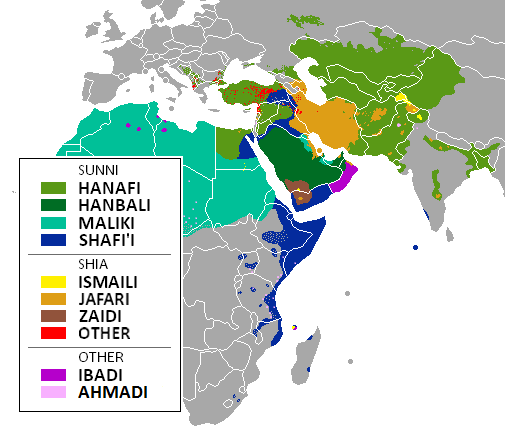

The main Sunni schools of law are Hanafi, Hanbali, Maliki and Shaf”i. They are associated with different territories as with any organized religion:

- Hanafi has the largest number of followers and is dominant in Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Egypt, parts of Iraq, India and Bangladesh, and a vast area to the east and north that includes most Russian Muslims

- Hanbali is strictly traditionalist and is dominant in Saudi Arabia and Qatar. The Saudi regime enforces a harsh, fundamentalist form of Hanbali known as Wahhabism

- Maliki is in Kuwait, Bahrain, Dubai and NE Saudi Arabia

- Shafi’i was the most popular school but was superseded by Hanafi under the Ottoman Empire

The major Shia traditions are the Fivers, Seveners, and Twelvers who differ on which of Muhammad’s successors are legitimate. The Twelvers’ Jaʿfarī is the school of law for most Shia Muslims because Twelvers are a majority in Iran and among the Shia Muslims in Bahrain and Iraq. They are also a significant minority in Lebanon.

Overall, around 85-90% of Muslims are Sunni, 10-15% Shia.

Now the events beginning in 1979 that made the Sunni-Shia split newly relevant.

The leading political movement in the Middle East in the 1950s and ’60s was Arab nationalism. Sunni-Shia distinctions were almost irrelevant then. The important issues were shared Arab ethnicity, which is different from Turks and Persians, and their long suffering under colonial powers who divided them.

What changed all that was Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution overthrowing the pro-Western shah. Iran’s theocratic revolution was both popular and anti-monarchist, and the new regime encouraged uprisings in other Middle Eastern nations. That threatened Saudi influence and their monarchy itself.

Then came the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq. The Saudi regime supported Iraq’s 1980s war against Iran to preempt revolution by Iraq’s Shias, but Saddam Hussein considered both Saudi Arabia and Iran enemies. Removing him disrupted the balance between the powers and left a power vacuum in Iraq.

Next the Arab Spring, starting in Tunisia in 2010, spread to Syria and other Middle East nations. Saudi Arabia and Iran, in rivalry for influence, amped up Sunni-Shia sectarianism. Their power plays, the Saudis’ heavily supported by the US and Israel, greatly increased the violence.

In Syria protests grew into rebellion then civil war. Rebels, encouraged by US policy to oust President Bashar al-Assad, were armed by the Saudi regime and Qatar. The Saudi regime wants Assad replaced by a Sunni government because Assad is Alawite, a Shia sect. They fear a potential “Shiite crescent” from Iran through Iraq and Syria to Lebanon. Seeing the civil war recast as anti-Shia, Iran’s regime encouraged Shia militias from Iraq and Lebanon to battle the Sunni rebels.

Those rebels include Al Qaeda’s Nusra Front, Ahrar al-Sham (funded chiefly by Kuwait), and Al Qaeda’s spinoff, the Islamic State.

Israel shares the Saudis’ fear of Iran. Shia group Hezbollah in Lebanon, one of whose chief goals is the elimination of Israel, gets substantial support from Iran. Sunni group Hamas, an offshoot of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, also seeks to establish an Islamic State in what is now Israel.

Meanwhile in Yemen, where civil war also rages, Saudi bombing, justified by greatly exaggerating Iran’s support for Houthi Shia rebels, has greatly worsened the humanitarian disaster.

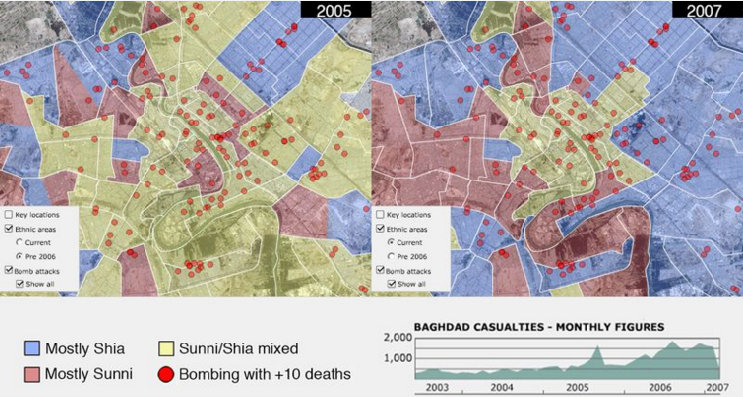

And meanwhile in Iraq, changes there illustrate how Sunni-Shia strife is not the norm. Iraq’s population is 75%-80% Arab and almost all Muslim, half to two thirds Shia. Saddam’s regime was Ba’athist, a movement aiming for a single Arab state that would be Muslim by tradition but more importantly, socialist (see comment.) Most of Saddam’s government were Sunni. Shia were oppressed by them, but there was little conflict between Sunni and Shia people until we made Iraq essentially lawless.

Sunni and Shia lived side by side in much of Baghdad, even in 2005. But as chaos grew, Sunni and Shia began to form self-defense militias, then saw each other as threats. Neighborhoods in Baghdad that had been mixed were starkly divided two years later.

The Sunni-Shia split is real enough to excite support for political leaders, but it is their contests for power that are the root of today’s Middle East violence. Our military interventions to prop up or topple these autocrats are counter-productive and greatly increase the suffering of the people.

Middle East conflict has spread to the USA only in the sense that we replaced the 20th century British and French Empires as the power whose actions aim to dominate the Middle East.

Should we be afraid of the variously named ISIL, ISIS or Islamic State? It is famous for beheading opponents and now controls most of Syria, but we do not condemn the Saudi regime for beheadings. Should we then support Syria being ruled by ISIL, a regime similar to Saudi Arabia’s?

No, we should stop being afraid, and we should stop compounding violence.