“Are you not in favor of quarantine?” I was asked in response to: http://martinsidwell.com/ebola-and-homo-politicus/ about how the media promotes fear.

I am in favor of helping us know when to quarantine ourselves and making it less difficult to do. I am against handing over more of our rights and responsibilities to our government.

What we have done so far to avert the risk of an Ebola epidemic is misguided. A few States have established mandatory quarantine of travelers from countries affected by Ebola in West Africa. Travelers from West Africa arriving at five US airports have their temperatures taken and are questioned about their possible exposure to Ebola. A 21-day quarantine was initially imposed on all travelers returning from West Africa whether or not they showed symptoms of the disease.

If the best approach were to quarantine all travelers from West Africa, it should be done at every international airport throughout the US.

But why only travelers from West Africa, and why not for other deadly diseases, too? If Ebola warrants such measures, shouldn’t we also close our borders to more deadly diseases? Those diseases are everywhere, so presumably we should quarantine all travelers from everywhere.

If we are willing to abandon more individual rights and responsibilities, we should temperature test all travelers, quarantine everyone returning from anywhere whose temperature is elevated and refuse entry to all non-natives with high temperatures.

Every passenger had their temperature taken and anyone with an elevated temperature was denied entry the last time I flew into China’s Tibet. We could do the same.

But Ebola is not in fact such a great risk for us in the USA. It has been contracted in this outbreak so far by around 10,000 people in West Africa since March and by around 400 health care workers from overseas, about 20 of whom have been treated in Europe and the US. That’s not many compared to other deadly diseases, but how contagious is Ebola?

Ebola spreads through direct contact with bodily fluids of someone who has symptoms of the disease. It can survive for a few hours on dry surfaces like doorknobs and counter-tops and several days in puddles of body fluid. Bleach solutions can kill it.

“Direct contact with bodily fluids of someone with symptoms of Ebola” means there is no risk of transmission from people who have been exposed to Ebola if they are not showing symptoms. No risk.

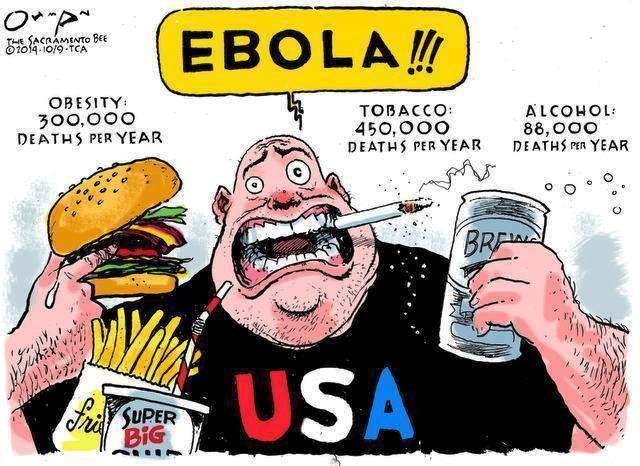

And the Ebola death rate is tiny so far compared to other contagious fatal diseases: fewer than 5,000 thousand Ebola deaths this year, hundreds of times more for other diseases. 1.6 million died from HIV/AIDS in 2012, 1.3 million from tuberculosis, 1.1 million from pneumonia, 760,000 from infectious diarrhea, and more than 600,000 from malaria.

The death rate from Ebola could greatly increase, but if closing our borders to it is wise, it is even more urgent to close them to HIV/AIDS and other diseases whose death rate is astronomically higher.

How much liberty and privacy are we willing to sacrifice, though?

Sacrificing our individual rights to our government is a slippery slope. Our fear of terrorists after 9/11 enabled passage of the Patriot Act, which severely restricted our traditional rights and made possible massive expansion of the NSA’s data gathering. Our fear after Pearl Harbor led us to incarcerate innocent people of Japanese heritage, which we eventually admitted was the result of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

Will we eventually reverse the excesses of the Patriot Act? Or will we abandon more of our liberty? Will we authorize the NSA to record everywhere we go using GPS data from our cellphones? They could then know who is at risk from contact with people who develop deadly diseases.

How much of our liberty and privacy are we willing to abandon in order to feel safer?

What have our politicians done so far? What they are always tempted to do, take more power. Is there a more effective possibility?

Yes. The risk of catching infectious diseases and their death rate is far greater in low- and middle-income countries where limited if any medical care is available. People travel, so disease travels with them. This means that by far the most effective way to cut our risk of contracting and dying from Ebola or other deadly diseases would be a universal health care system.

Everyone in the USA who contracts a contagious disease could then receive medical treatment and not infect others.

That is the best approach for our people, but what about those in West Africa? Should we do anything for them?

That’s a moral question. Facts and analysis cannot provide the answer, although there are practical aspects we can consider.

We currently feel obligated to act as the world’s policemen. We give our government several trillion dollars each year to destabilize cruel regimes. But those who survive the bombing fail to establish better government. That results in us being hated, despised and/or laughed at for our foolishness.

Killling and destruction do not make life in this world better. We could, however, build a happier world by instead acting as its humanitarian leader. We could, for example, do more than send 3,000 troops to Liberia to build 17 Ebola treatment facilities.

But we seem to have no compelling self-interest in West Africa as we do in the Middle East without whose oil our economy would collapse. If Ebola arrives in India’s slums, however, and sparks a widespread epidemic, our cancer, HIV-infected and other patients will not get their medicines because 40% of generic drugs in the US come from India.

We do have interests throughout the world, and our behavior is noticed. If we stop killing people to make their lives better and instead help them heal themselves, we will be more loved, less hated and therefore much safer.

It is hard to imagine us overcoming out feeling that we must rule the world, however, and almost impossible even to imagine our government building a better situation for our own people in our current political climate.

What does seem somewhat realistic is to avoid Ebola hysteria. Let’s instead of foolishly sacrificing more of our rights, require our government to educate us about Ebola and make it less difficult for anyone with symptoms to quarantine themselves and get treatment.