As we enjoy our fine breakfasts of potato curry, my Korean-American friend tells me Korean is better for people because the usage changes depending on their relationship. It’s not just the greeting, the suffix of many words also changes. Interactions are not effective if the wrong form of language is used.

What this means is when Korean people meet, they must immediately work out how they are related. “I must pay close attention to you. I can’t just start blah, blah, blah as I would to an American. The language forces me to be more sensitive to other people.” I knew Japanese was like this and associated it with a stilted, hierarchical culture. Koreans, my friend says, are very different. “We are fiery people, always yelling at each other. But because of our language we do it respectfully.”

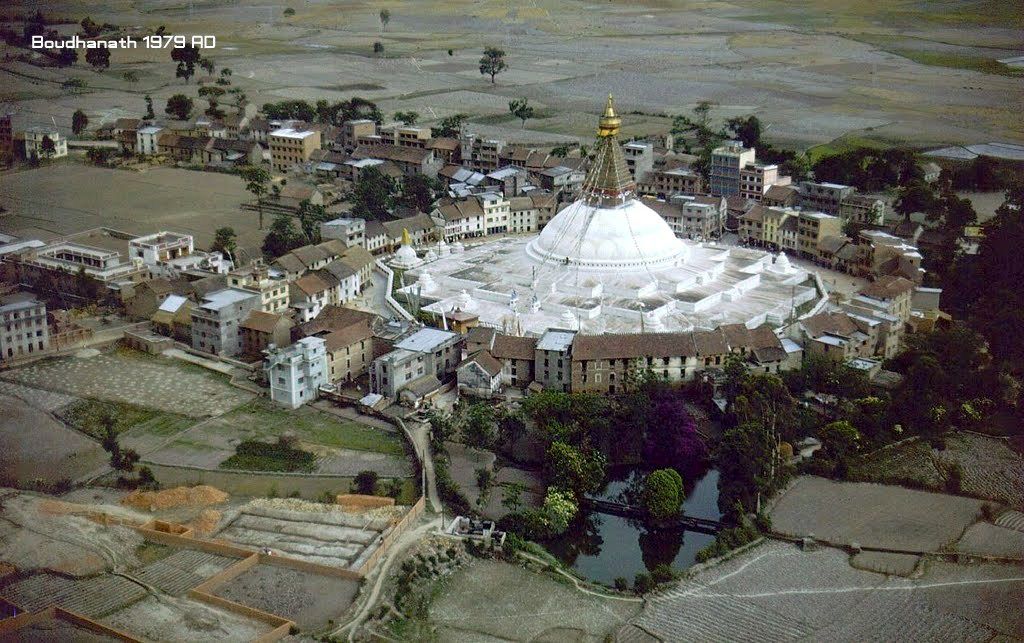

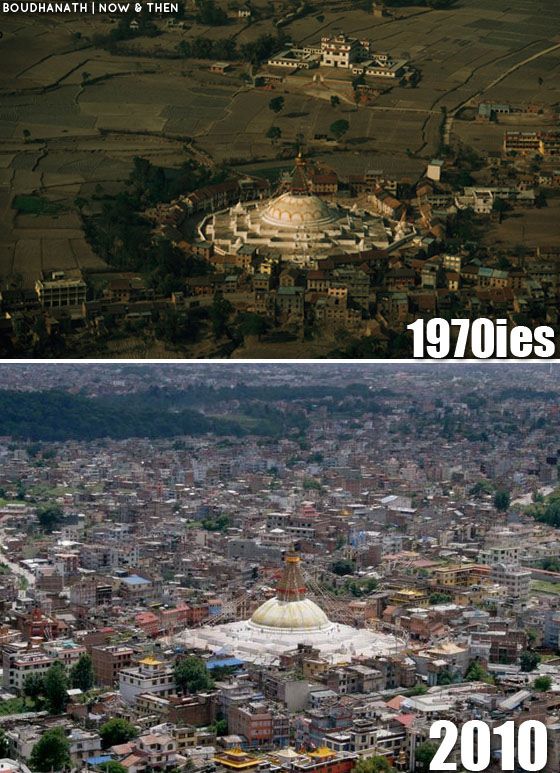

Westerners also assess relative relationships. Think of a business gathering, think of a social gathering, think of any gathering. We treat people differently depending on what role we imagine for them, and we can imagine simultaneous different roles for the same person. Chokyi Nyima Rinpoche, the head of a big Tibetan monastery here in Boudha, who travels extensively to give teachings, said with a big smile one day last year: “It’s very strange. Sometimes people treat me like a great teacher. They say, “oh, you are such a great lama’ and they bow to me. Other times they treat me like a baby who cannot do anything for himself.”

How does communication actually work? Do we need concepts about others to interact effectively? Does facial expression, for example, tell us more? Recent research provides a surprising answer.

A researcher with photographs of faces of people who had won or lost a tennis match asked folks to say who had won and who lost. Then he showed photographs of the whole body of the winners and losers. Lastly, he showed losers’ faces photo-shopped onto winners’ bodies and vice versa. Shown faces only, people were wrong as often as they were right. With entire bodies they usually guessed correctly. We imagine faces reveal what’s in our mind but in fact, it’s body posture.

Surely eye contact is important? Sherry Turkle has been studying social technology for thirty years at MIT. When I met her in the mid-90’s she was cautiously optimistic about virtual communities where adolescents (and others) can try out different personalities and learn better ways to interact. No eye contact there. She recently published a new book about not only social technology but the impact of always-on smartphones and also caring robots. She is troubled by how these technologies amplify self-absorption. Robots that make eye contact are especially seductive.

If a robot follows us with its eyes and responds to our words or gestures, we imagine it cares about us. It fits our concept of interaction. We are in fact happy to imagine the emotion that does not exist, maybe happier because that’s safer; we’re in control. One of Sherry’s research volunteers was playing with her grand-daughter when her robotic “seal” was delivered. Captivated by its responsiveness, happily imagining its need for food and sleep and responding to that, she soon ignored the real child.

Are concepts of interaction ever helpful? My sheep didn’t seem to have concepts about each other. Mothers and their lambs baa’d if they got separated. Pairs of adult ewes sometimes interacted by standing nose to nose breathing lightly. In both cases information was exchanged. Was it correctly understood?

Maybe that’s not the right question. Sheep and other creatures are programmed not to evaluate but respond instantly to input that might signify a threat. There’s little or no cost when the threat is not real and great benefit when it is. They, too, are imagining more than is being sent but in their case, it’s a survival mechanism. Chickens run from an aircraft shadow because it could have come from a hawk

There is a form of communication that provides perfect information exchange. Computer-computer communication includes extra data with each message so the receiver can know if the message was corrupted, and extra messages so the sender knows if the message reached its destination correctly. Getting that to work is harder than it sounds – the network whose development I managed starting in 1971 took a couple of years to debug – but this is a case where message sent and received are identical and there’s no imagining of additional content.

The goal of humans communicating seems less clear. We are happy to communicate with robots even though we fabricate the emotional content of message received. We are often unhappy communicating with each other because what’s said is ambiguous and/or what’s heard is misinterpreted. Why does this happen? Because our interactions are formed by concepts about others and what kinds we like, don’t like or don’t care about.

Suddenly, I see the big thing. Korean helps us notice we are speaking with a real person not an imaginary playmate. Grandma’s robotic seal has the opposite effect, seducing her into an imaginary relationship in which she ignores her real grand-daughter.

We so easily imagine we’re communicating when all we’re really doing is entertaining ourselves.