This story about Everyman exploring where he does not know the language has a deceptively deep point.

We enter the story as Everyman asks his guide “What’s that?” pointing to something intriguing. It’s the same every time and so frustrating! He understands none of the few words reply.

They walk on. Suddenly, through a gap in the trees, Everyman notices an odd looking building.

“What’s that?” he asks, pointing to the building, and again understands none of the few words reply.

Now the path leads up. From the crest he sees a beautiful stone structure that seems to overlook the next valley.

“What’s that?” he asks, pointing to the beautiful structure, and yet again understands none of the familiar reply.

So it goes every day.

Then one day they happen upon a man who speaks not only Everyman’s but also the local language.

“I don’t understand,” Everyman says. “Every time I want to know what something is I ask my guide, but I never understand his answers and the really odd thing is, it feels like he always says the same thing!”

“Show me what you mean.”

“OK.” Everyman beckons the guide over, nods to him and points to a colorful bird on a nearby branch. “What’s that?” he asks, and the guide replies.

“There!” Everyman exclaims. “What did he say?”

“He said, ‘It’s your finger, you fool.'”

The point of the story is we think words are the names of things when in fact, they just point toward “things.” If we don’t see what is being pointed toward, we imagine words to mean what we already think they mean.

My experience working to understand, experience and embrace Buddhist metaphysics has been much like that of Everyman and his guide.

The ethics are the same but the Buddhist understanding of existence is fundamentally different from what I learned growing up. The difficulty is, all the words available to express that understanding already have meanings in my mind.

I soon realized I must work to see what is different that familiar words are pointing towards. That takes persistent effort and what is very unfamiliar to me, persistent relaxing.

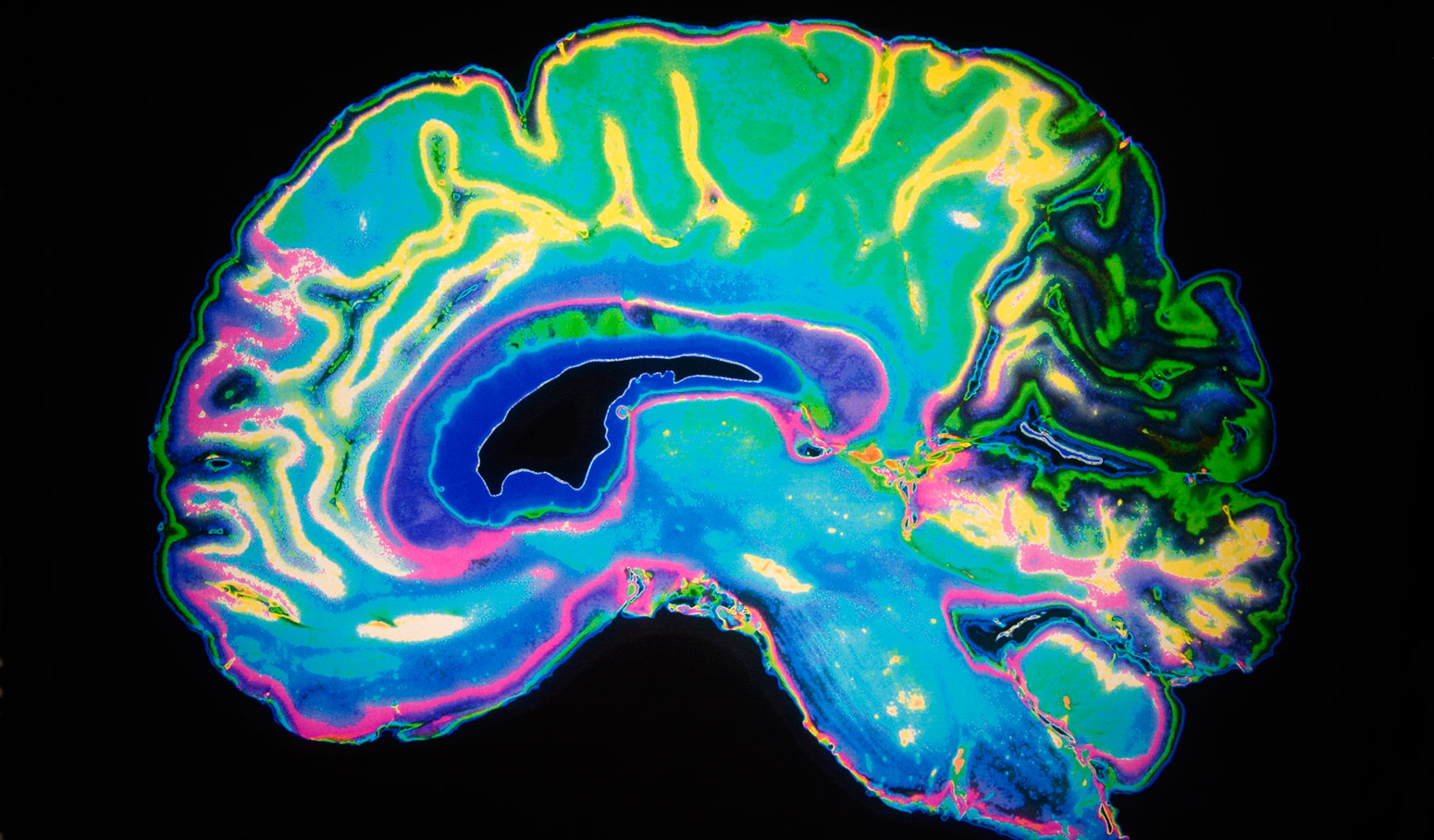

There’s meditation that calms the mind, like waiting for the wind to slacken, because it’s hard to see clearly in our usual mind-storm.

There’s close observation and rigorous analysis that make it possible to recognize what is real.

And there’s chanting poetry, a disorienting ritual practice that facilitates the experience of what is real.

I’m so blessed to have been introduced to three approaches to the ineffable — poetry, physics and practice!