Nepal’s political morass has not changed in the months I was gone. Progress is stymied by too many squabbling children in politician bodies crying “mine, mine, mine”. How did it get this way? Does history of the US Constitution offer guidance?

A transitory coalition of the other 5 leading parties recently announced they would no longer attend public meetings where Maoist Prime Minister Baburam Bhatterai or anyone else in his unappointed government is present. The parties are united in wanting his government to fall, at odds on what should happen next. The government is unappointed in the sense that there was no provision for what would happen if the Constituent Assembly (CA) failed to draft the new Constitution.

When the CA was dissolved in May four years after its two year term began, Prime Minister Baburam said (a) we need an election to establish a body that will do what the CA failed to do, (b) we need a government in the interim, and (c) the existing government should stay in place to hold elections asap. The second largest party, the Nepali Congress (NC), said that’s OK but Baburam must resign in favor of an NC leader. Baburam said that’s no good because the President, who had the authority to disband the CA, is a member of the NC. There would be too much risk the NC would hang on to power until they thought they could win an election. If we want to make a change, he said, we should choose a coalition government for the interim.

It’s not clear how a coalition government would differ from what’s already in place nor how the politicians could ever agree who would make up the Cabinet. The NC can’t even agree which of them would replace Baburam in the impossible event anyone else agreed to that. Meanwhile the smaller parties make transitory alliances to promote specific agenda items that cannot be implemented in the current situation, anyway.

The leader of a party that recently split off from the Maoists published a 90 point demand. One third of these demands relate to India, including that Indian vehicles must be banned from Nepal, Hindi movies must not be shown and Hindi music must not be broadcast. The leader said his party would begin enforcing the demands nationwide and immediately. Like other such initiatives, even the ones that makes sense, that soon fizzled out.

Having failed to accomplish what they were elected to do, the politicians fear they will not be reelected. The one thing they can agree on is it’s best to keep delaying a new election. It’s not clear how those not in the Cabinet are getting paid but it’s never clear how money flows in this society. Transparency International reports that Nepal is the only South Asian nation whose Corruption Perception Index has worsened in the last seven years. To get a government-financed contract, contractors must pay 50% of the project budget to politicians and civil servants who could block it. Only 20% to 30% of the budget is spent on the goods or services provided. They are inevitably of poor quality.

For some, the argument over the number of States in Nepal is philosophical; broader representation (more States) vs strengthening Nepal as a nation (fewer States). For others, it’s personal. Tribal leaders allegedly fighting for their people but wanting access to the money trough, “Nationalists” wanting to preserve the Hindu establishment’s lock on power, the breakaway party motivated by anti-Indian prejudice and seeing high caste Nepali Hindus as “really Indian”.

How did it get this way? A regional prince who conquered his neighbors and unified the territory paid his generals with rent they could collect from newly conquered land. After further conquests were halted by British India and imperial China the monarchy was pushed aside by the Rana family and, under new ownership, Nepal continued to be operated as a private family tax farm. No industry developed because Nepal has no coal, oil or useful minerals and its geography makes transport very hard. Subsistence farming was supplemented by petty trading. One third to half the total economic output went to the center as rent. Many men left to be soldiers in the British Indian army. When the Ranas fell 60 years ago the monarchy was restored. Foreign aid began to arrive but much was siphoned off by the elite. Almost the only government Nepal had ever had that was for the people was in villages with a good head man. No surprise that apart from tourist services there are still few alternatives to getting a position to extort bribes, getting property to rent, or working abroad.

How important is a new Constitution for Nepal? A nation’s Constitution is much like a business strategy; every business should have one and it should not be a bad one but several good ones could be successful. A well executed good strategy will always beat a less well executed better strategy. So Nepal’s politicians just need to choose one of the good ones, apply it diligently, and adjust as conditions change. To illustrate, let’s take a quick look at the US Constitution that was established with equally high hopes and, as it happens, around the time Nepal first became a nation.

The US Constitution reached its current form in three stages. First, the structure and purpose of government was articulated: (A) three branches of central government to make, enforce, and interpret the law, (B) the roles and powers of central and local governments, and (C) what the national government would provide the people, namely justice, civil peace, common defense, things of general welfare they could not provide themselves, and freedom. It was adopted in 1787 by a Constitutional Convention, ratified by conventions in eleven states and went into effect in 1789. Next, ten amendments known as the Bill of Rights were proposed in Congress and came into effect in 1791 after approval by three-fourths of the States. It had been too hard to agree everything at once. In the third stage, the Constitution undergoes periodic clarification and/or amendment. It refers, for example, to “the people” but the rights it asserts for them were understood for very many years to apply only to white men. Rights for American Indians, African Americans, women and others were adopted much later.

The US Constitution does not specify the nation’s borders, or the borders between States. US territory greatly expanded after the Constitution was adopted and some State boundaries changed. The Constitution is not explicit about whether States could secede and form a new nation. The 1860s Civil War aka War of Northern Aggression established that the southern States would not be allowed to do that. The great ongoing debate, however, is about the third element of the Constitution, the social contract, what the central government should provide to the people and how it should do so.

How have the first three Amendments, presumably considered to be the most important, stood the test of time?

The first amendment says: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” This may be the most important principal in the entire Constitution. The devil, however, is in the details. How much freedom, for example, should there be about speech on behalf of political candidates? My freedom is abridged if my campaign contributions are limited but if there’s no limit, I can in effect silence you. Estimated contributions for the most recent US election range up to $6B. Because US politicians now need so much money to get elected they must depend on a wealthy few to whom they must deliver correspondingly big favors. So a side effect of the Constitutional right to freedom is, at this time, a corrupt central government.

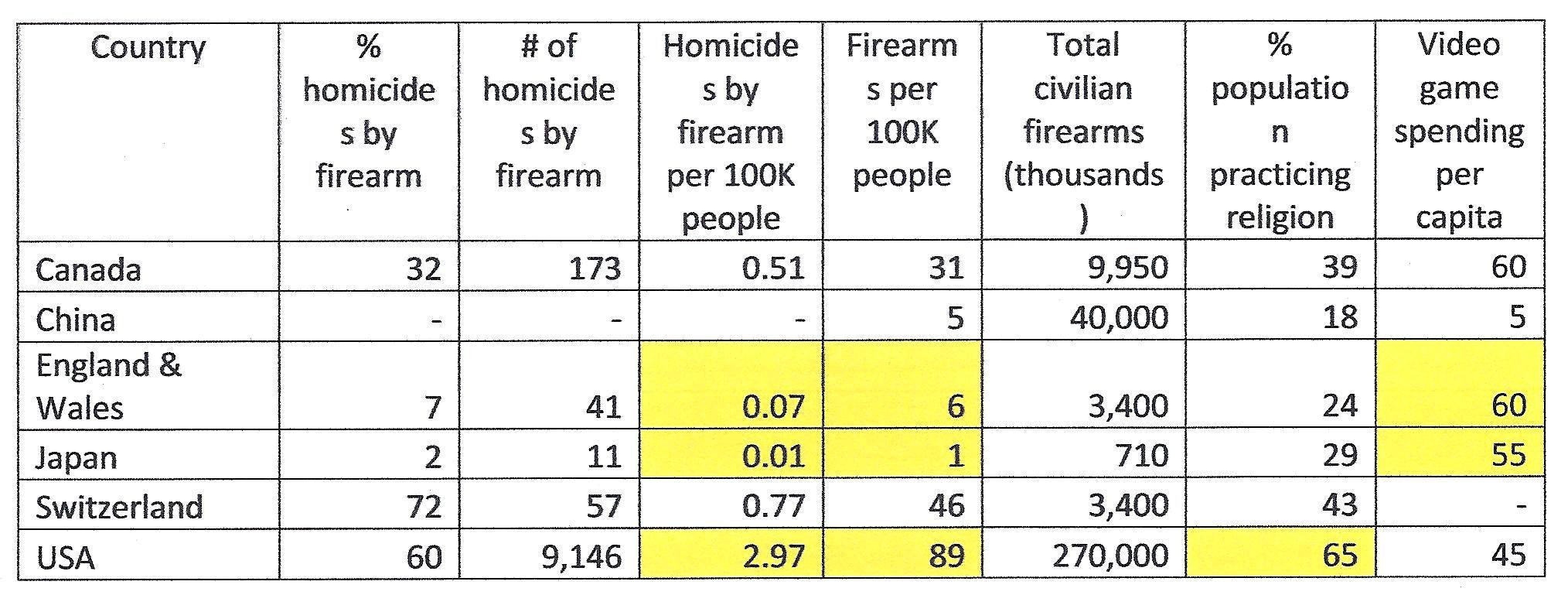

The second amendment says: “A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed”. The intent of that tortured phraseology, at a time when only single shot firearms existed, was to prevent the central government from tyrannizing the States and, by implication, its citizens. There was no need then to define what kinds of Arms the people could bear. The federal government now has nuclear arms, however, and killer drones. Does this Amendment mean the States and “the people” also have the right to them? Nobody I know believes that but many Americans support the right to bear assault weapons (I’ll say more about that in a future post). Some even imagine they must have assault weapons to defend against central government attack.

The third amendment says: “No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law”. Although this Amendment has long been entirely irrelevant it continues to be enshrined as part of the Constitution.

What conclusions should Nepali politicians draw from this and other nations’ Constitutions and from the above examples, (1) a profoundly important right that also has a deeply corrupting effect, (2) an important safeguard when the Constitution was established that is now ineffective against that risk and creates unanticipated new dangers, and (3) a provision that became completely irrelevant ?

First, since several structures of national government have proven to be effective, Nepal’s politicians should just choose one and start governing. Second, they should not imagine that even the most finely crafted Constitution will guarantee what the people get from their government. Third, some Constitutional provisions will need significant update when conditions change and not all will remain relevant, anyway. Above all, what is important is good governance. The time for that is now.