Our War on Terror strategy (see this) implies readiness for large and small scale action in multiple theaters throughout Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia, Southeast Asia, and Northern and Western South America. How likely is its success, how long will it take, can we afford the cost, and is there a better approach?

The goal of the strategy is to eliminate Islamic “holy war” terrorists who might attack us from anywhere in the world. It is unachievable. That kind of threat can not be ended, only mitigated and endured. Military action is in fact counter-productive because the collateral destruction creates more terrorists and strengthens their support. Even if we could utterly destroy al Qaeda, we could not declare victory because we declared war on all Muslim terrorists. Since there are over a billion Muslims, there will always be a few Muslim extremists just as there will always be some who are Christian.

Response to aggression should always be proportional to the threat, and it must be able to succeed. Our response is massively disproportional and it can never succeed.

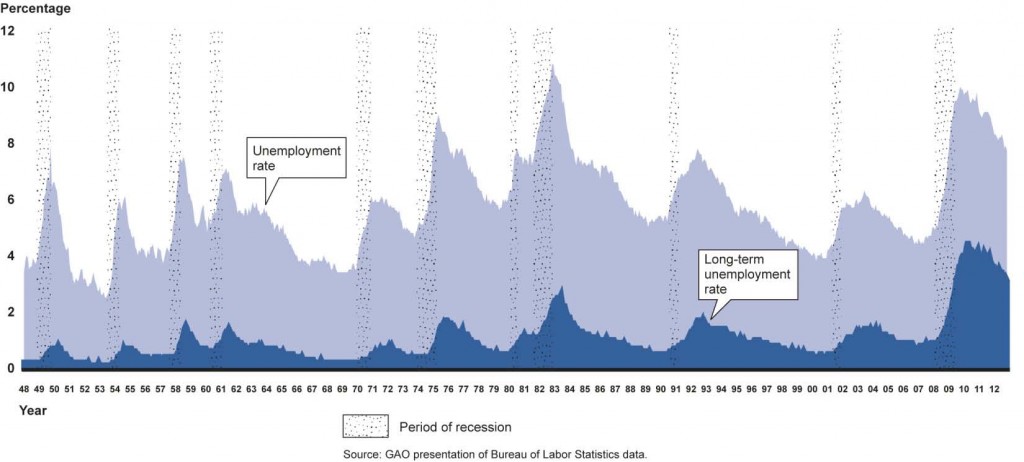

A strategy of unending military engagement everywhere would exhaust any nation. That strategy for the USA predates the War on Terror. We spend more on military activities than the next 20 nations combined, which is half our total expected Federal tax revenue. The cost of our already high Federal debt must become unaffordable when our spending is persistently so much higher than revenue. No nation can afford war that is permanent. We cannot afford this strategy’s cost.

And the strategy will make us permanently less free. When we go to war to preserve our liberty, we willingly forgo some of the freedoms we enjoy in everyday life, expecting them to be restored when victory is achieved. If victory never can be won, those freedoms never will be regained.

Finally, the strategy creates unwarranted suffering for our own people. Enormously more of our troops are killed than the number of US citizens threatened by terrorists and enormously more of them suffer physical and/or psychological damage from which they will never recover. Caring for them has a high dollar cost. Far more important, we are wrong to demand their sacrifice.

So, we are forcing future generations to pay for a war that cannot succeed and which limits the very freedoms we claim it will preserve. How did this happen?

For the first half century after we emerged as a great power early in the 20th century, we acted overseas only after deliberation and then with decisive power. The great good fortune of our geography gave us time to prepare and sufficient resources to do so. We entered WW1 and WW2 when we were ready and we brought about rapid victory.

We radically changed strategy following WW2. We began managing the world whether or not our immediate interests were threatened in any particular situation. We took the lead in Korea, which the Allies had split into two nations at the end of WW2. Then we initiated a long, bloody and fruitless war in Vietnam that spilled over into Laos and Cambodia. And we established a nuclear strategy of “mutually assured destruction” which we did not change after Soviet Russia, our only military rival, collapsed and we no longer faced any existential threat.

In response to the 9/11 attack on two mainland USA targets by al Queda terrorists, we initiated not just detective work but war, as if we had been attacked by a nation. We invaded Iraq even though we knew there was no Iraqi involvement in the attacks. We heavily bombed Afghanistan where al Queda’s leaders were based and inserted ground forces there. After Al Queda’s command cell relocated to Pakistan, we greatly increased our activities in Afghanistan. By about 2004 we had lost focus on what our War on Terror was intended to achieve.

No satisfactory reason for our invasion of Iraq emerged, civil war broke out, and opposition to us was so strong by 2004 that we could only maintain our presence by allying with our enemies. Furthermore, by destroying Iraq’s power we had eliminated the only regional balance against Iran, which we now view as our enemy. After entering Afghanistan to disrupt al Qaeda’s leadership, we drifted into fighting the Taliban, a different and far more costly objective that required massive force. We then, as in Iraq, set a far longer term objective, building a democratic society. When we installed the Karzai government, the Taliban retreated to the mountains to wait us out. We are now downsizing our presence but the end of our war in Afghanistan is indefinitely far distant.

Meanwhile, we began to capture and monitor all electronic communications to identify terrorists. Believing we were threatened by potentially massive new attacks, we could only hope to avert them by monitoring all communications between everyone, and storing everything so we could monitor earlier communications of new suspects. We partially suspended habeas corpus so suspects could be jailed indefinitely without trial. We began torturing them, illegal in the USA even in wartime, in camps overseas. We began killing suspects without due process. The President can now direct even US citizens to be killed.

In the past 10 years we have killed around 3,000 terrorists and civilians with drones in Pakistan, Somalia, Yemen and elsewhere, i.e., inside nations on which we have not declared war, and the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), which killed bin Laden, has established commando teams in Africa for operations throughout NE Africa and the Middle East. Attorney General Holder asserts: “Our legal authority is not limited to the battlefield in Afghanistan… We are at war with a stateless enemy, prone to shifting operations from country to country.” That authority extends, he says, to killing US citizens without regard to geography or due process.

War changes society by limiting citizens’ rights. Inspecting the private communications of citizens is routine during war, habeas corpus and due process are routinely suspended, and what would be assassination in time of peace becomes legal. But if our war on terror never ends, our civil liberties and peacetime rules of law will never be restored. They will be further eroded.

We are now, 12 years into this war, committing massive resources to missions that are not even clearly connected with preventing Islamist terrorism and we are making permanent what were introduced as emergency overrides on the Bill of Rights, e.g., the need to obtain a warrant for certain actions.

No nation can afford the dollar cost of permanent war or the spiritual cost of war that can never be won. When we do take military action it should be with clear goals and sufficient force applied in a way that will achieve the goals. Our present strategy has none of these attributes.