Social Security was originally established as insurance. The Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance Act (OASDI) was for those who became unable to support themselves. At that time, during the Great Depression, the poverty rate among senior citizens was over 50%. OASDI became a pension plan a half century later when in 1983, President Reagan sponsored an increase in Social Security taxes, changing the program from pay-as-you-go to collecting more than it paid out. When OASDI was established, life expectancy was only 62 and benefits became payable at 65. Ever-improving medical technology raised life expectancy, however, and folks came to expect they would live long enough to get a Social Security pension. The change made in 1983 recognized that new reality. Boomers would prepay part of their old age benefits.

Social Security then began accumulating a surplus. It took in $95 billion more than it spent last year and ended 2011 with a $2.7 trillion surplus. Of course, surpluses every year forever were not expected. The accumulated surplus would at some point start to be drawn down and what was taken in would be brought into balance with what was paid out. But now there’s a new factor; not only is life expectancy increasing, the birth rate is dropping. That means fewer workers contributing to Social Security as well as more people getting benefits. We now have 66% workers and 14% folks 65 or older. The US Census Bureau projects that by 2050 we will have 60% workers and 21% folks 65 or older. That means the ratio of contributors to benefiiciaries will plummet from 5:1 to 3:1.

Even so, our demographic prospects are better than most. China has 74% workers and 9% 65 or older today but is projected to have 60% workers and 27% 65 or older in 2050. Its working age population is projected to be 200 million lower by 2050 while ours will be 50 million higher. Nonetheless, our steeply dropping ratio of contributors to beneficiaries must be acted upon and it will get worse unless we also increase job creation. Social Security trustees project the program will start to pay out more in 2021 than it takes in and the surplus will be gone in 2033. Only enough tax revenue will then be collected each year to pay about 75% of benefits.

An additional issue is that the Social Security surplus was supposed to be invested in interest-bearing federal bonds but there is no trust fund in the sense most of us imagine. That $2.7 trillion surplus was already spent on other things. It exists only as a part of our overall federal debt. It is, of course, backed by the full faith and credit of the US government.

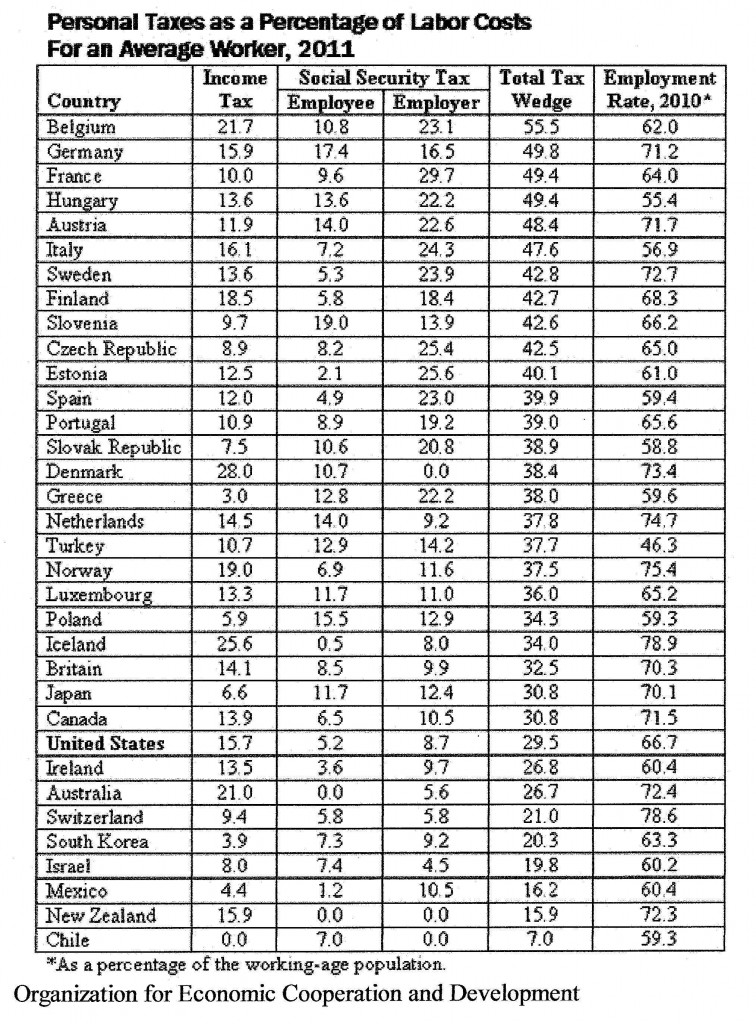

And there’s one more very important change to consider. Social Security taxes increased in the last half century while income taxes shrank. From 1961 through 2011, Social Security taxes grew from 3.1% of GDP to 5.5%. Personal income tax dropped from 7.8% to 7.3%, most of that decrease benefitting those in the top 1% of incomes (the top rate fell under Reagan from 70% to 28%). Corporate income tax fell from 4% to 1.2% (the rate fell from 50% of profits to 35%). What happened, in other words, is corporate income tax fell by 2.8% while Social Security taxes increased by an almost identical 2.4% and since Social Security tax is capped, most of the burden of the tax increase was born by the bottom 90%.

So now it’s time for another major update of the Social Security program. What could we do? What should we do? And when should we do what?

The AP recently used data from the Social Security Administration to calculate how much of the projected shortfall would be eliminated by various options. To highlight the urgent need for action, they also calculated what would have been eliminated if those options had been adopted in 2010. I’ve also incorporated some data from David Cay Johnston. First, what could we do and why should we do something soon?

1) We could raise the payroll tax ceiling to generate more revenue. If we restore the Reagan standard that 90% of wages are taxed instead of today’s 83%, the tax would now apply to close to $200,000 of wages not $110,100. Workers making $200,000 in wages would get a tax increase of $5,574. If we entirely eliminate the ceiling and levy the tax on all wages, we would eliminate 72% of the shortfall. Two years ago, we would have eliminated 99%.

2) We could also generate more revenue by raising the tax rate. If we raise it by 0.1% a year for 20 years until it reaches 14.4% versus the current 12.4% (of which workers and employers each pay half but for 2011 and 2012, employees temporarily pay only 4.2%), workers making $50,000 a year would get a tax increase of $500. That would eliminate 53% of the shortfall. Two years ago, it would have wiped out 73%.

3) We could also get more tax revenue by increasing wages, which had fallen in 2010 back to the 1999 level, and by creating more jobs, which grew at only a fifth the rate of population increases since 2000.

4) Or we could cut the outflow by raising the retirement age. If we gradually raise it from 66 for full retirement benefits (67 for those born in 1960 or later) to 68 in 2033, that eliminates 15% of the shortfall. Two years ago, it would have eliminated 20%. If we go to 69 in 2039 and 70 in 2063, that eliminates 37% of the shortfall. Two years ago, it would have eliminated half.

5) We could also cut the growth of payouts by changing the inflation index that governs benefit increases. If we use the Chained CPI, which assumes people change what they buy when prices increase, that would eliminate 19% of the shortfall. Two years ago, it would have eliminated 26%.

6) Or we could reduce benefits for those with lifetime wages above the national average, currently about $42,000 a year. If they still got more than lower paid workers but not as much more as now (the average monthly benefit for a new retiree is $1,264), we could eliminate 34% of the shortfall. Two years ago, we could have eliminated almost half.

Which of these options should we adopt?

Since the fundamental problem is the greatly increasing ratio of those getting pensions to those contributing to the program, option (4) seems appropriate. The AP only calculated the result of raising retirement age from 67 to 70. We could go further. When Social Security was established, most folks expected to continue supporting themselves throughout their life. The idea that most of us can retire is quite recent. But the issue with this line of thinking is that those who most need the Social Security retirement benefit have low wage jobs that tend to be least suitable for older people. Those with higher paying jobs can invest in their own pension plans, can more easily continue working while their body ages, can better mitigate the effects of aging, and are more likely to have work that remains attractive. So maybe we should also adopt option (6) because higher income folks can increase their retirement benefits by investing in a supplementary plan. Option (5) seems a gimmick, a way to avoid addressing the underlying challenge.

Our culture has changed enough in the last century (I hope) that winding down Social Security is not an option. Most of us now need an employer so we can support ourselves, and we need to be well enough to work. More people do become self-employed when there’s a persistently high lack of jobs but they will never be more than a minority in today’s economy. Granted, we have many people living on the streets begging and/or thieving, we support by far the world’s greatest number of citizens in jail, and we have people benefitting from Social Security who should be working, but most of us now favor OASDI because we know people can’t always get a job. If today’s Great Recession degenerates into another Great Depression, only the uber-rich may disagree.

So the more difficult question is to what extent we should increase Social Security’s revenue. Recall that the payroll tax ceiling was higher under Reagan and we could (option 1) eliminate much of the projected shortfall by reinstating that level. We could also secure the program’s finances by slowly raising the tax rate (option 2). That seems reasonable since future beneficiaries are likely to receive more benefits for a longer time but I prefer option (1), eliminating the ceiling altogether, because that would partially reverse the 1961-2011 shift in tax collection from high to lower income folks. Our society was not improved by that shift.

The greatest challenge is implied by option (3), increasing wages and creating more jobs. It’s easier to imagine an accelerating reduction in the number of jobs for humans as more and more jobs can be done by computers and robots. I touched on this in other posts and will return to it in more depth. Planning for society with only the jobs that will still be available to humans in 2050 may be our greatest strategic challenge. But today we need to address the more immediate problem, preventing Social Security from being defunded.