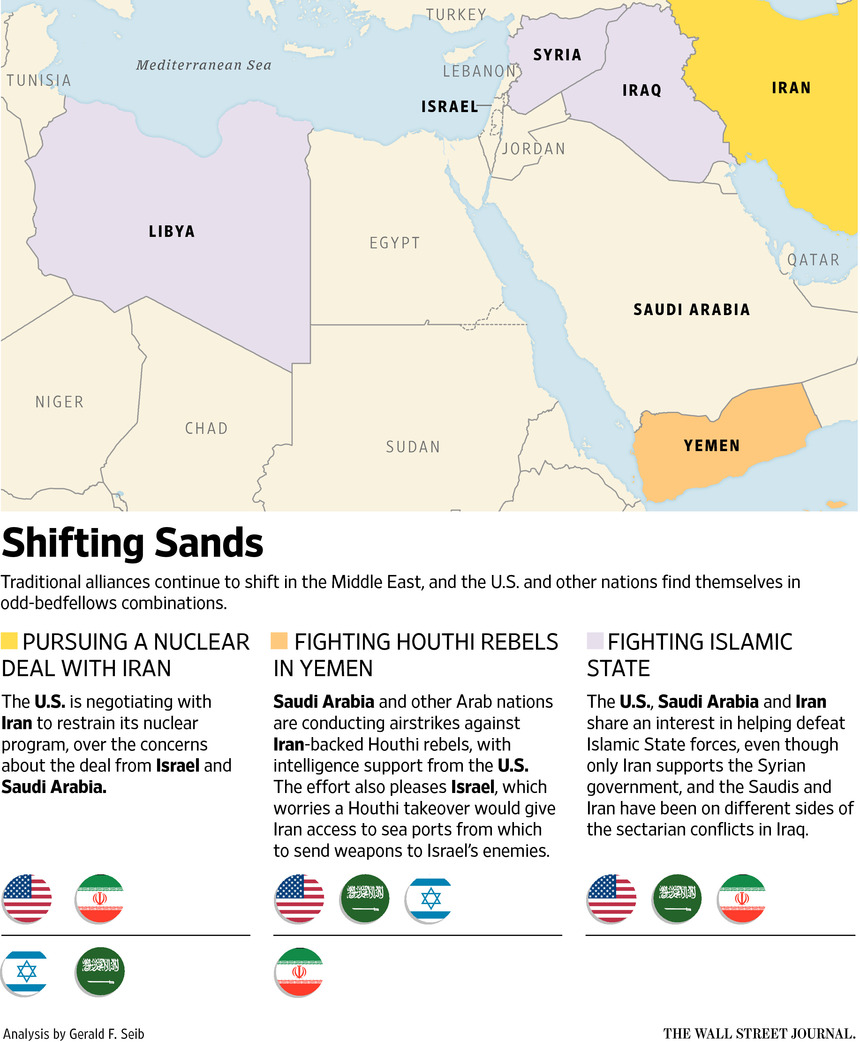

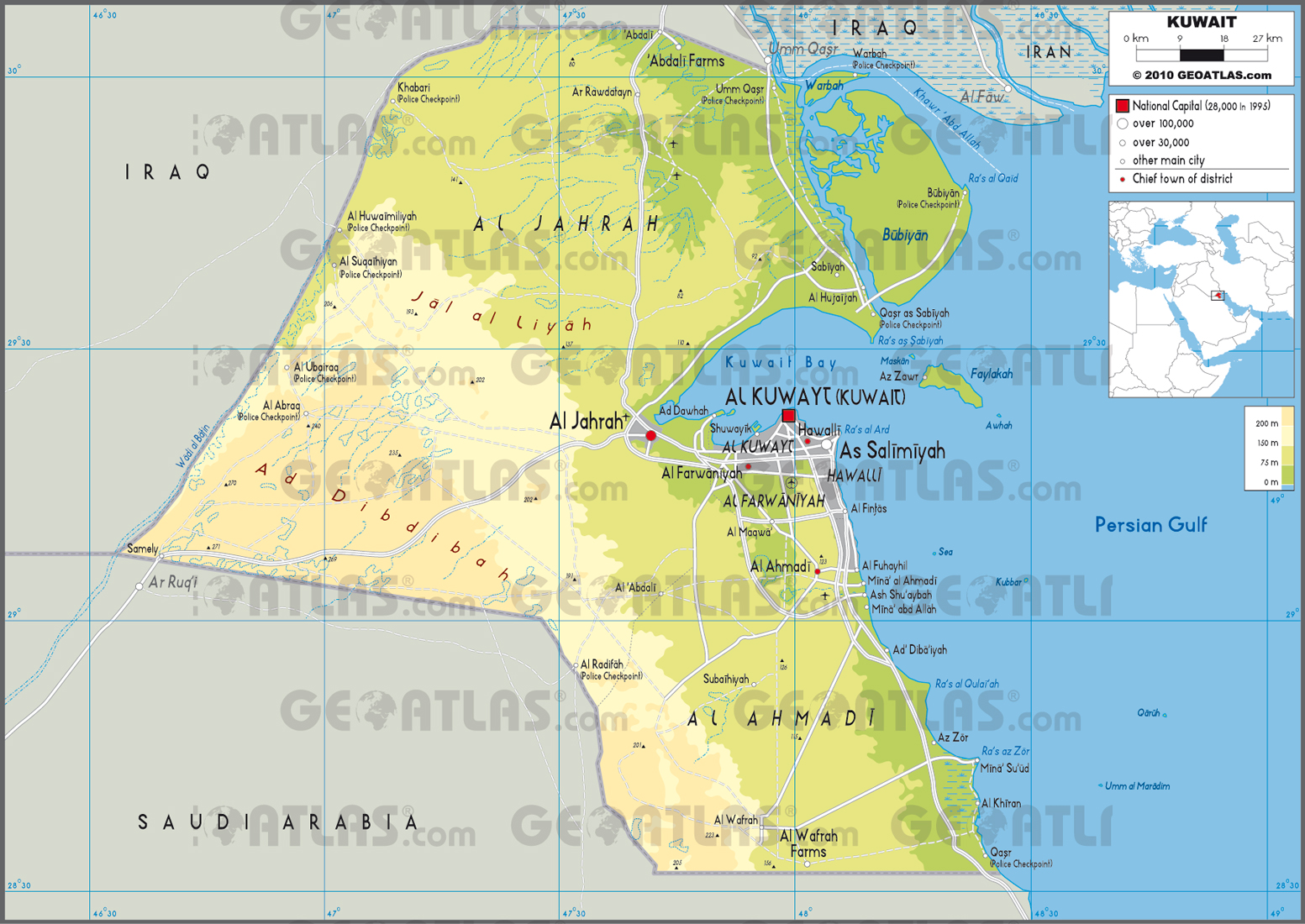

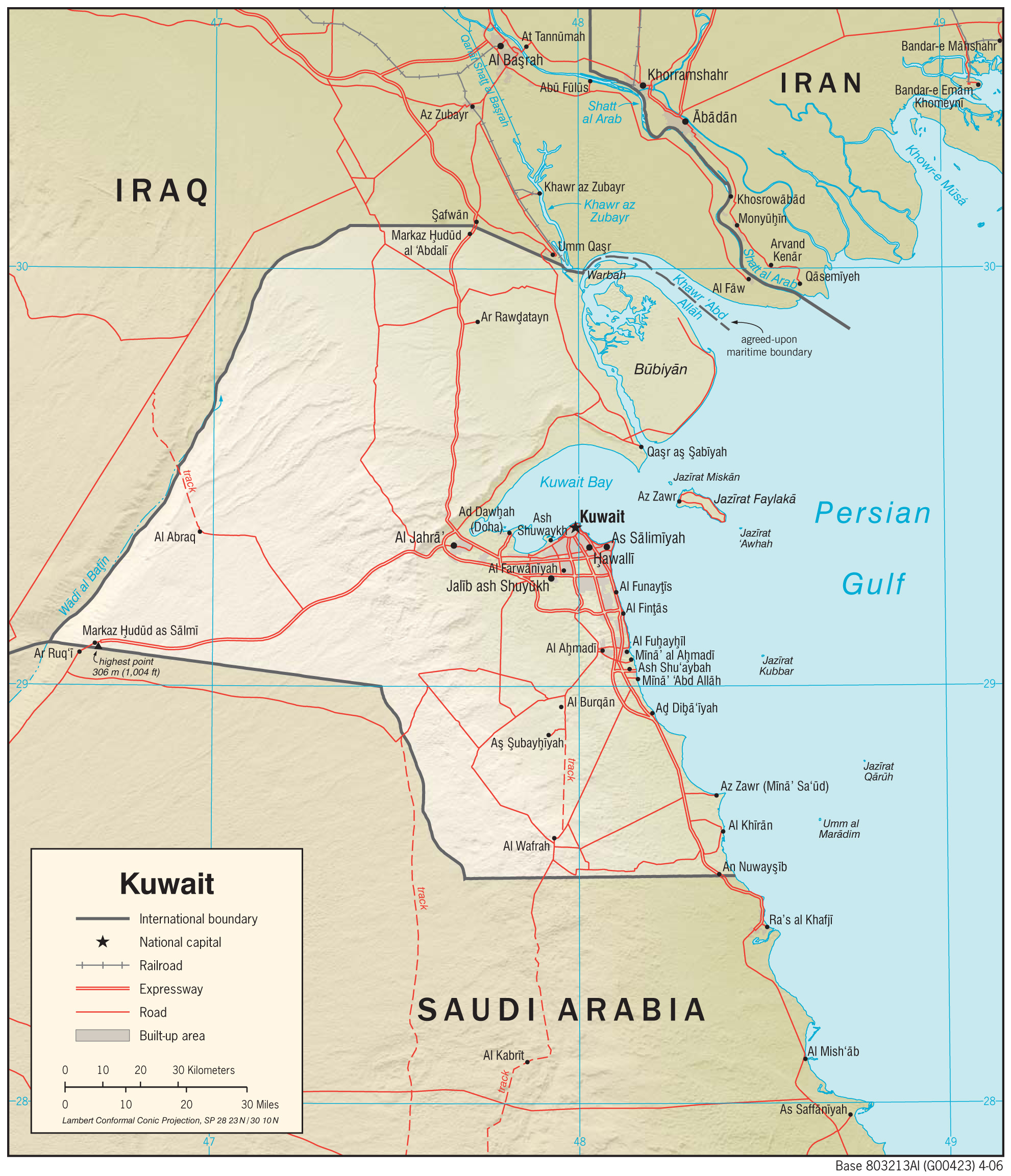

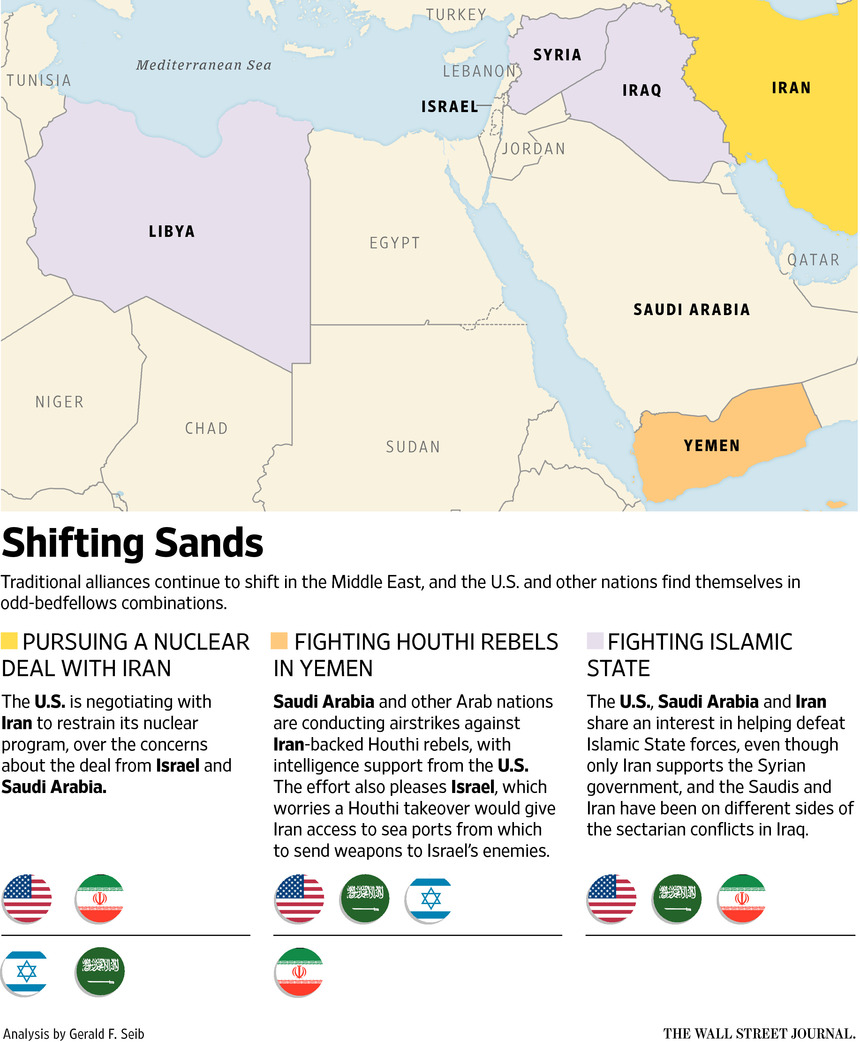

Why is it harder to “understand” Palestine than Lebanon or other Middle East states? Because Palestine lacks the conceptual framework of statehood. It does not even exist on this map of Middle Eastern states that aims to illustrate the incoherence of our current alliances.

The map’s precise borders suggest stability, too. Although Iraq, Libya, Syria and Yemen are sunk in civil war, they seem to be unified like currently stable Egypt, Iran, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.

Previous posts in this series have begun to illuminate the deep conflict between long-powerful Iran and recently-wealthy Saudi Arabia, why Yemen has become a proxy in their rivalry, and how Jordan, Lebanon and Syria became independent states. Now we can explore why Palestine did not become one and start to think holistically about what is driving Middle Eastern conflicts.

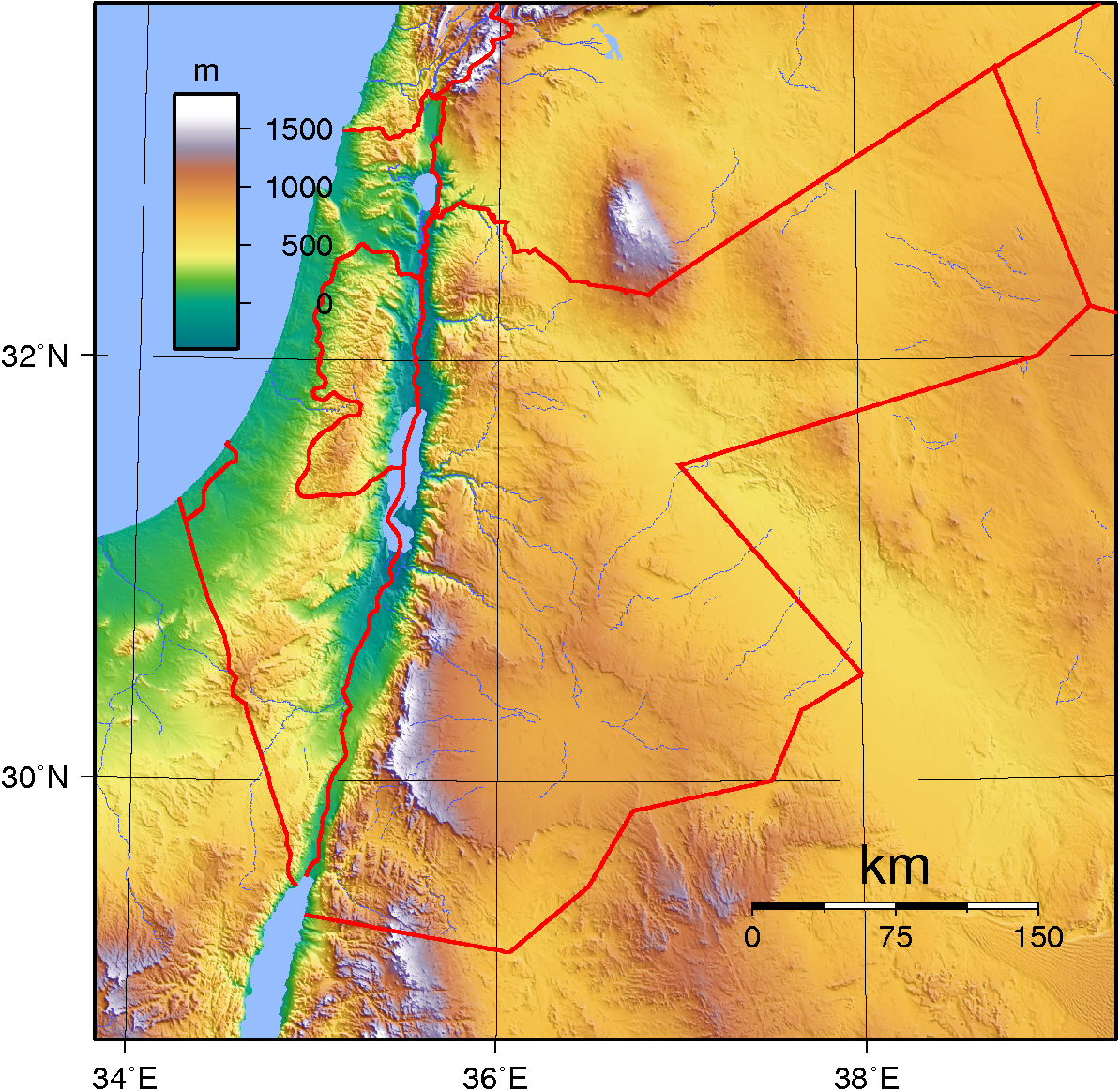

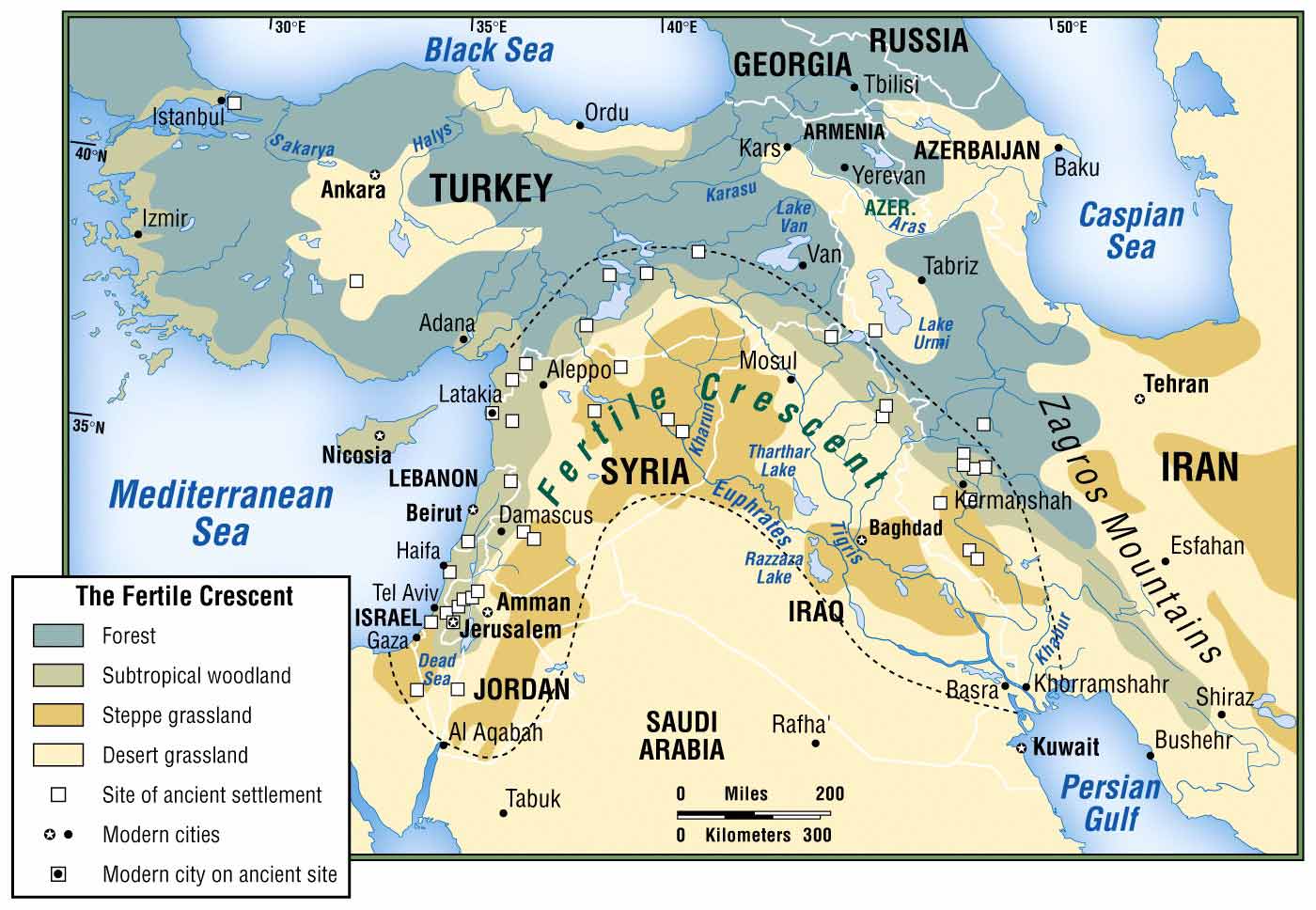

The region between Egypt, Syria and Arabia known for thousands of years as Palestine was among the world’s first settled agricultural communities. It is a crossroads for commerce, cultures and religions, the place where Judaism and Christianity were born. Controlled over the centuries from Egypt, Persia, Greece, Rome, Turkey, Britain and more, its boundaries changed constantly.

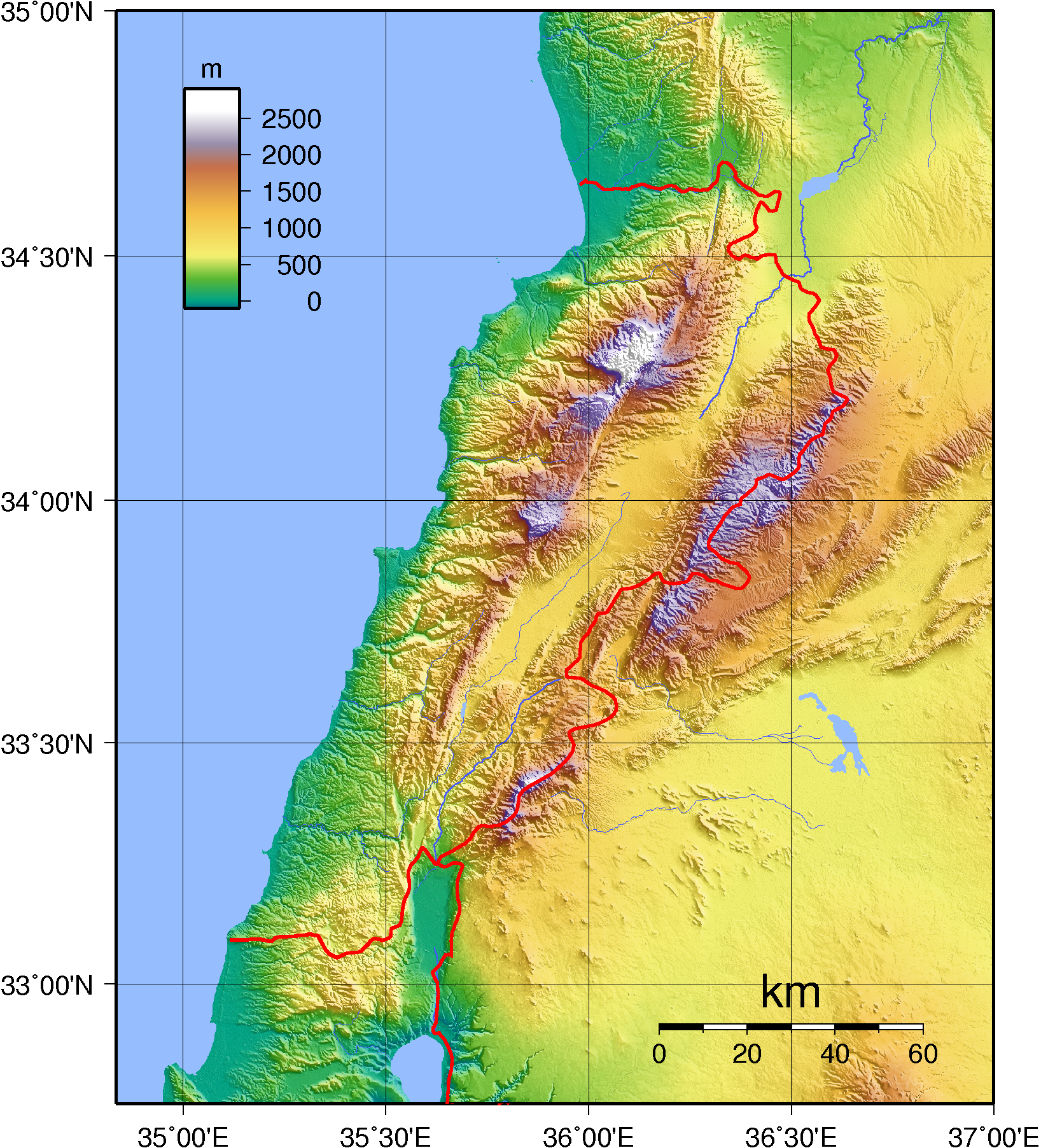

Today’s Palestine is part of what was Greater Syria under Turkey’s Ottoman Empire. That Syria was the entire region from the Mediterranean to the Euphrates and the Arabian Desert to southern Turkey’s Taurus Mountains. When the Ottomans got control by conquering Egypt in 1517, they subdivided it into administrative districts, some of which correspond to today’s states.

When the Ottoman Empire fell at the end of WW1, the League of Nations granted Britain and France Mandates over the region. Those Mandates placed former German and Turkish colonies under the “tutelage” of Britain and France “until such time as they are able to stand alone.”

Note: If that sounds patronizing, it is worth noting that it is what we are currently trying to do in Iraq and Afghanistan.

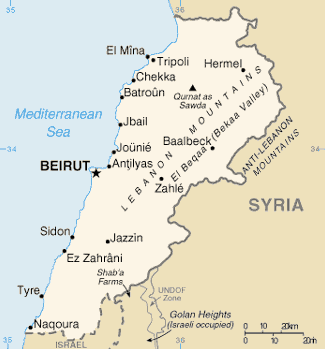

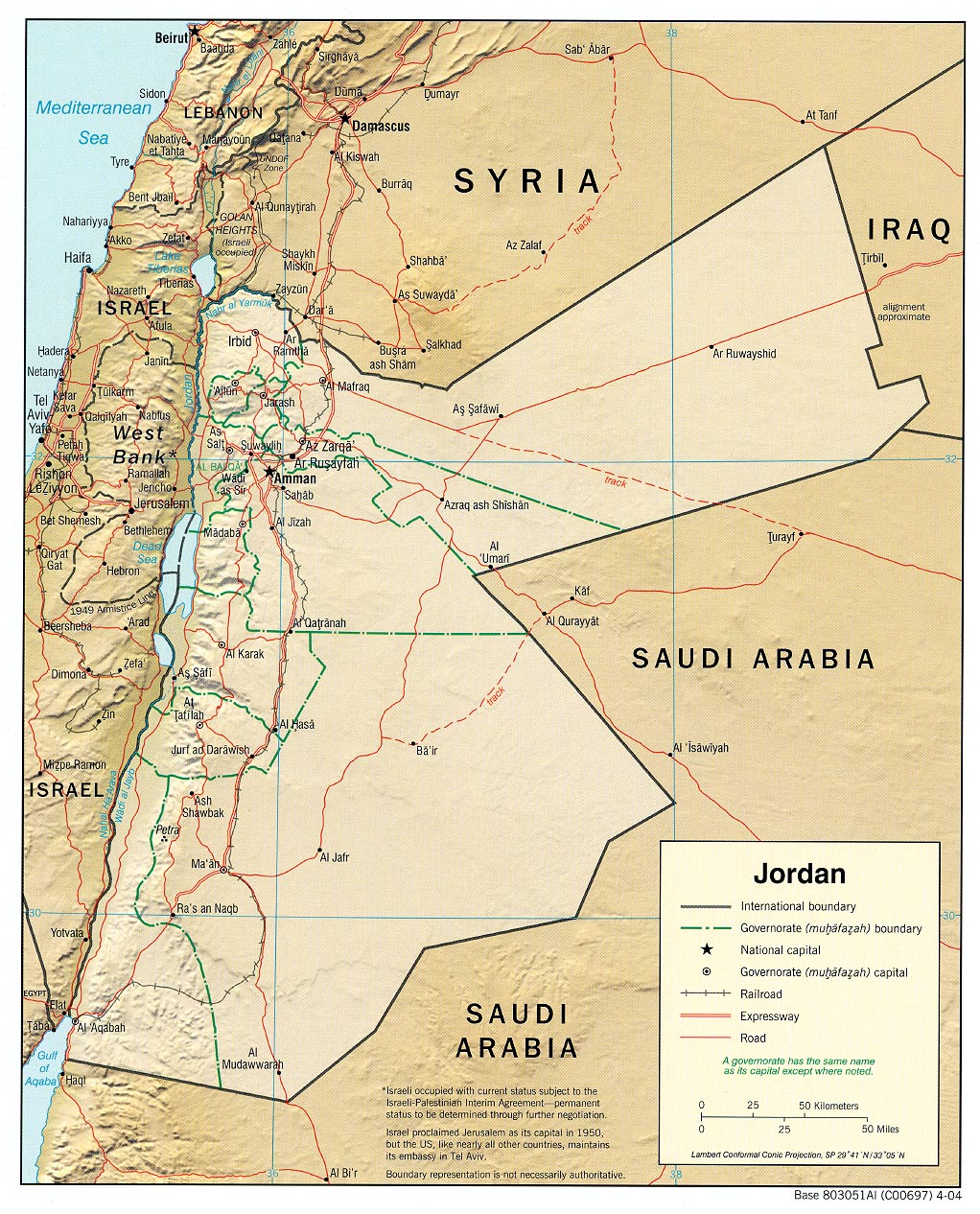

Having secretly agreed during WW1 how they would divide it between them, Britain and France established states in their mandated territories. That was when Lebanon and Syria became separate nations. Britain divided its territory into Palestine and Transjordan, which later became Jordan.

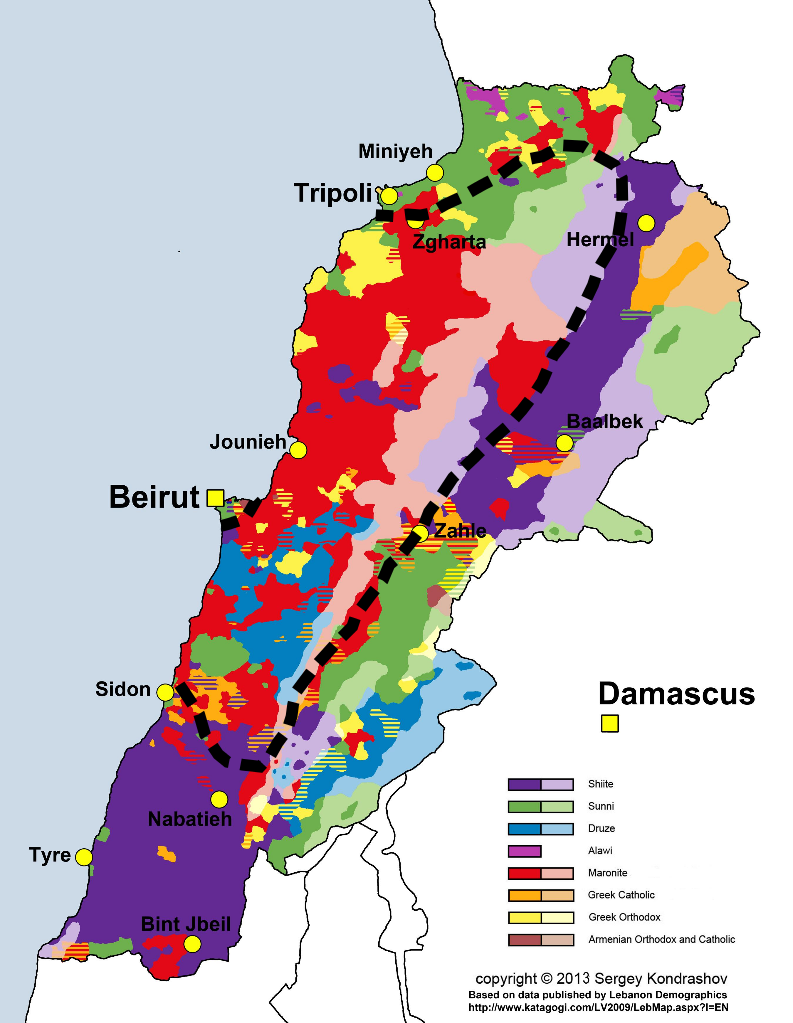

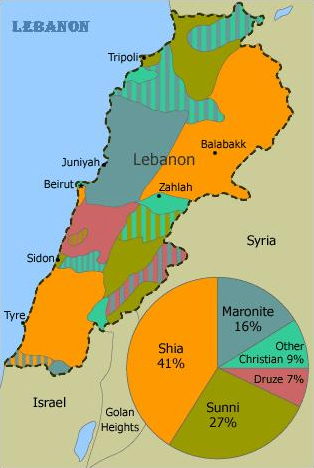

Europe’s concept of nation states had come to the Arab world late in the 19th century. It gave rise everywhere to a growing rejection of colonialism and in Greater Syria to the theory of a pluralistic Syrian nationality that supported multiple religions: Sunni and Shia, Christian and Jewish.

The idea of an independent Palestine within Greater Syria arose when Britain established Mandatory Palestine with a modern nation-state boundary. The desire for that independence greatly increased as a result of fast growing Zionist immigration into what is now Israel.

The Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) founded in 1964 to liberate Palestine by armed struggle was secularist then like Greater Syria even though about 90% of Palestinians are Sunni.

Islam only became significant in Palestinian politics with the 1980s rise of the Hamas offshoot of the Muslim Brotherhood founded in Egypt in 1928 as a religious, political, and social movement.

But let’s take a step back. How did Ottoman Greater Syria become home to diverse people and religions, and what is the specific history of today’s Palestinian State?

The Roman Empire began converting to Christianity when it was reunified by emperor Constantine. His mother brought Christianity to Jerusalem in 326 and Palestine grew to become a center of Christianity. Although Greater Syria was conquered by Muslims in 636, the majority of its population remained Christian until the late 12th century.

Persecution of Christians began growing in the late 10th century during a long series of wars between Egyptian, Central Asian and Persian Empires and Europe’s Crusaders. Then the decline of the eastern remainder of the Roman Empire in the early 13th century dramatically cut Christian influence throughout the region.

In the early 20th century, Zionist settlers began buying land in what is now Israel and evicting Palestinian peasants. At the same time, support began growing in Britain for the establishment there of a Jewish homeland.

Muslim-Christian Associations formed throughout the area in opposition and became a national group that agitated for an independent Palestine. Protests grew as mass Jewish immigration continued. The protests developed into a 1936-1939 mass uprising.

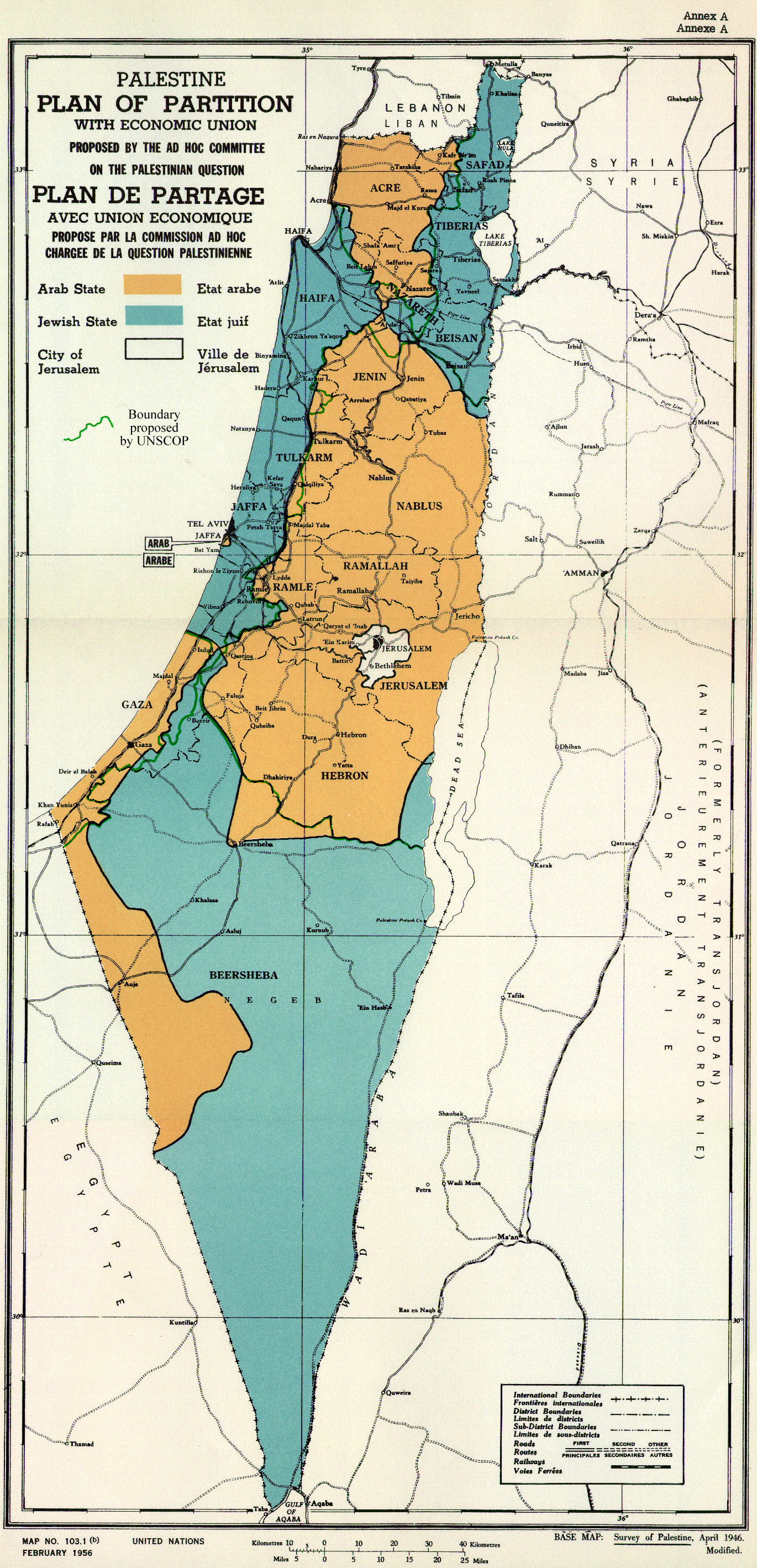

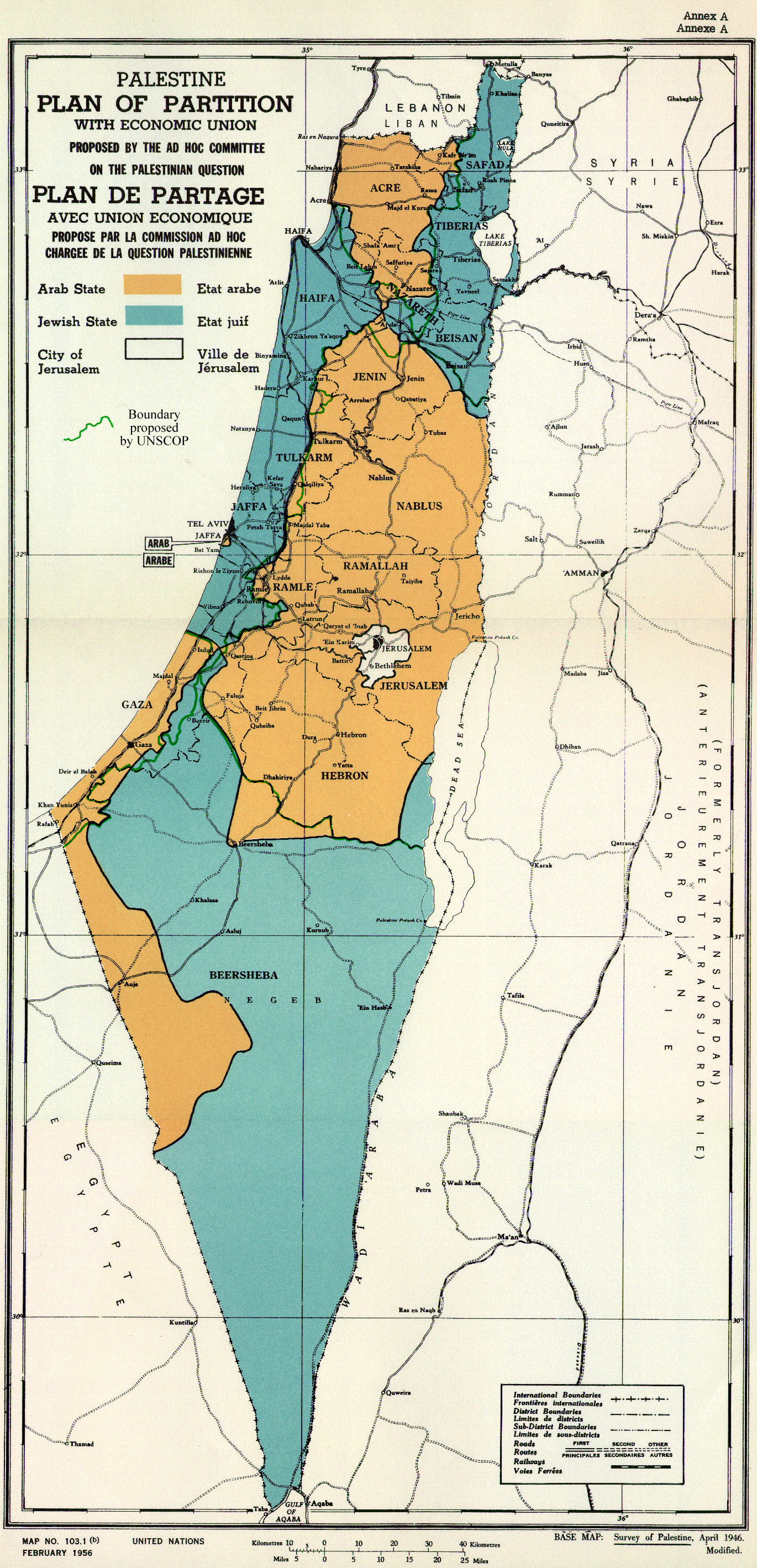

After WW2 in 1947, the UN proposed the partition of Britain’s Mandatory Palestine into an Arab state, a Jewish state and the Special International Regime for the City of Jerusalem.

Palestinian leaders along with those of Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Yemen, Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Turkey, Greece, Cuba and India rejected any such plan of partition saying it violated the UN charter’s principle that people have the right to decide their own destiny.

Although Palestinian and Arab leaders now accept the partition in broad terms as a fait accompli, they continue to consider it unfair.

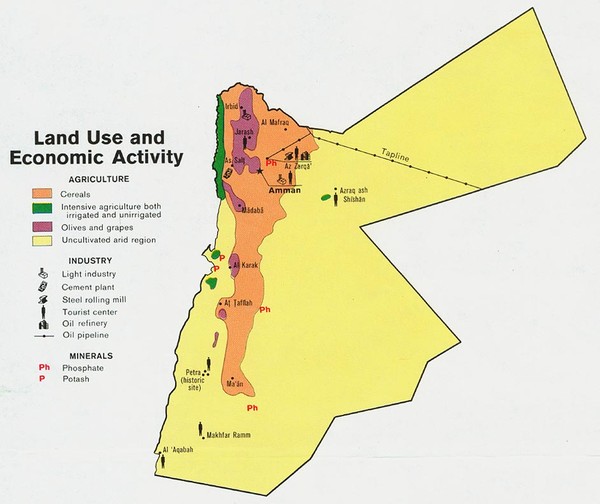

Jews owned 7% of Mandatory Palestine but were given 56% of it. The area under Jewish control contained 45% of the Palestinian population. Much of the Arab land was unfit for agriculture.

The Negev desert given to the Jewish state was also sparsely populated and unsuitable for agriculture but that area was a “vital land bridge protecting British interests from the Suez Canal to Iraq.”

Note: To understand Palestinians’ reaction, imagine the UN establishing Native American homelands corresponding to where they lived before Columbus and returning 56% of the USA to them.

Civil war broke out. It became an inter-state war when Israel declared independence in May 1948. Forces from Egypt, Jordan Syria and Iraq joined the Palestinians but Israel ended up with both its UN-recommended territory and almost 60% of the proposed Arab state.

Civil war broke out. It became an inter-state war when Israel declared independence in May 1948. Forces from Egypt, Jordan Syria and Iraq joined the Palestinians but Israel ended up with both its UN-recommended territory and almost 60% of the proposed Arab state.

Jordan took the rest of the West Bank and Egypt the Gaza Strip. No Palestinian state was created.

During ten months of battles, around 700,000 Palestinians, 60% of all those in Mandatory Palestine in 1947, fled or were driven out. In the following three years, about the same number of Jews immigrated to Israel, 110% of those in Mandatory Palestine in 1947.

Note: Again to put numbers in perspective, imagine 193 million Americans (60% of of 321M) being driven out in less than a year and replaced in the next three years by the same number of Muslim immigrants (who we imagine already make up 15% of our population).

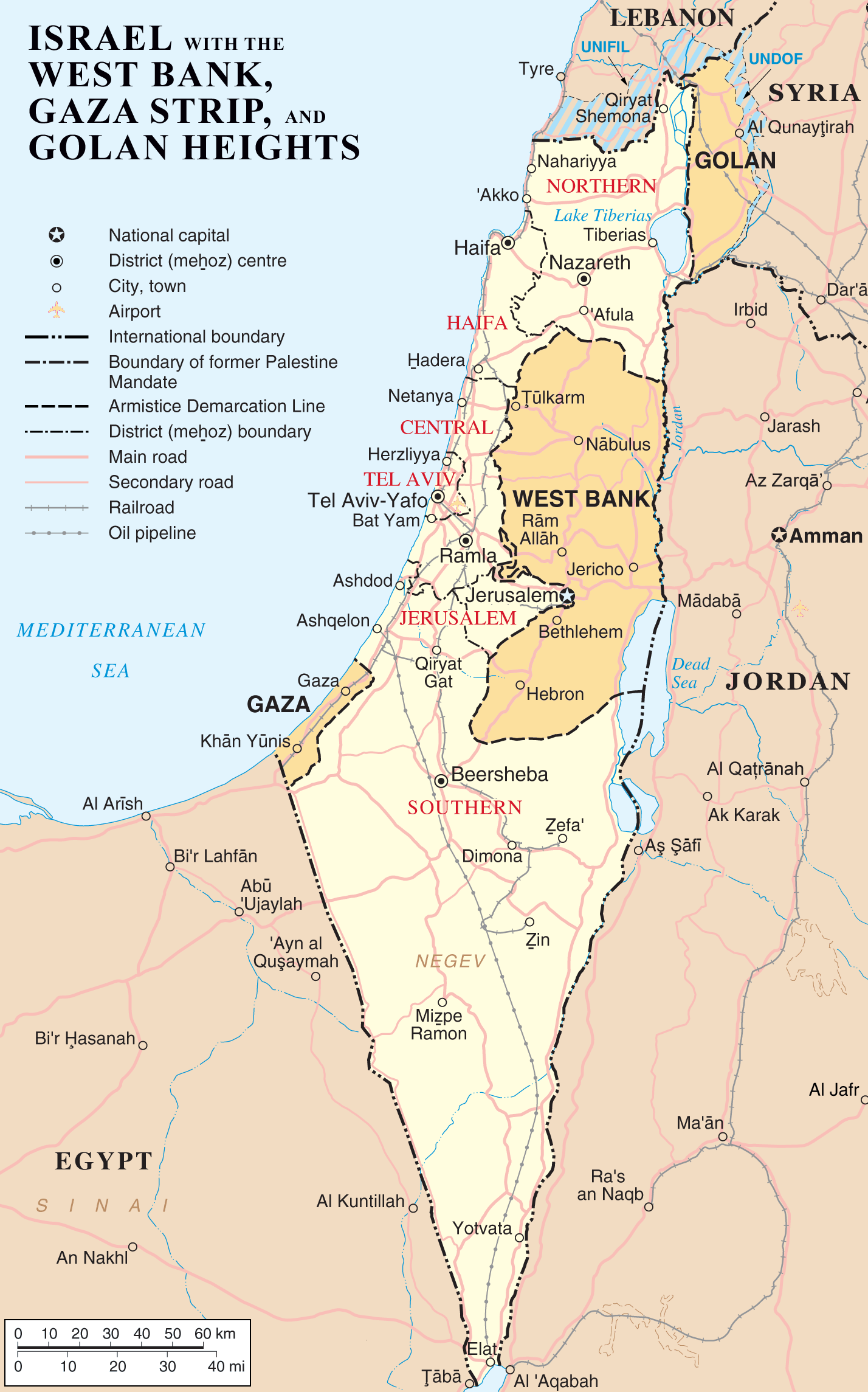

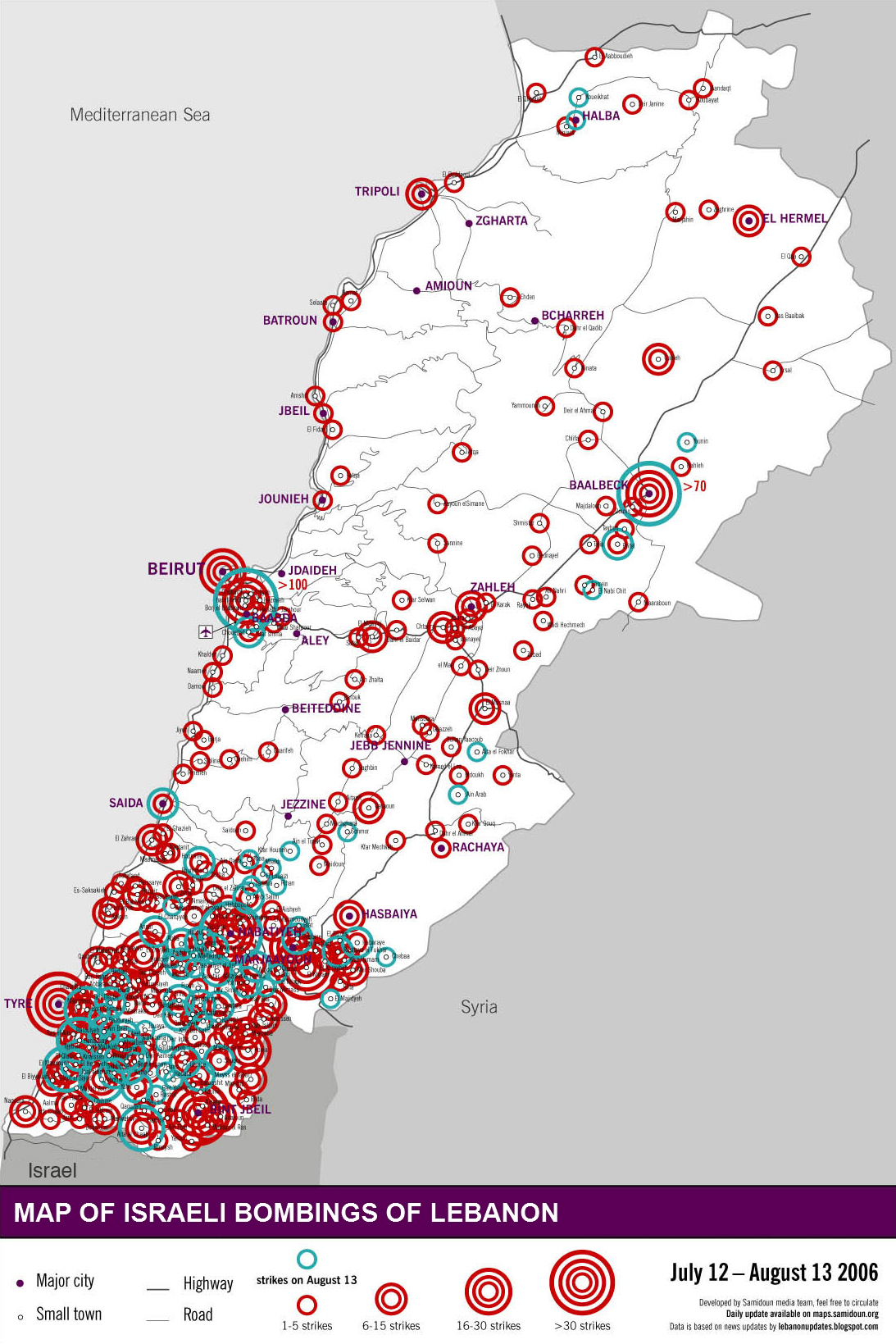

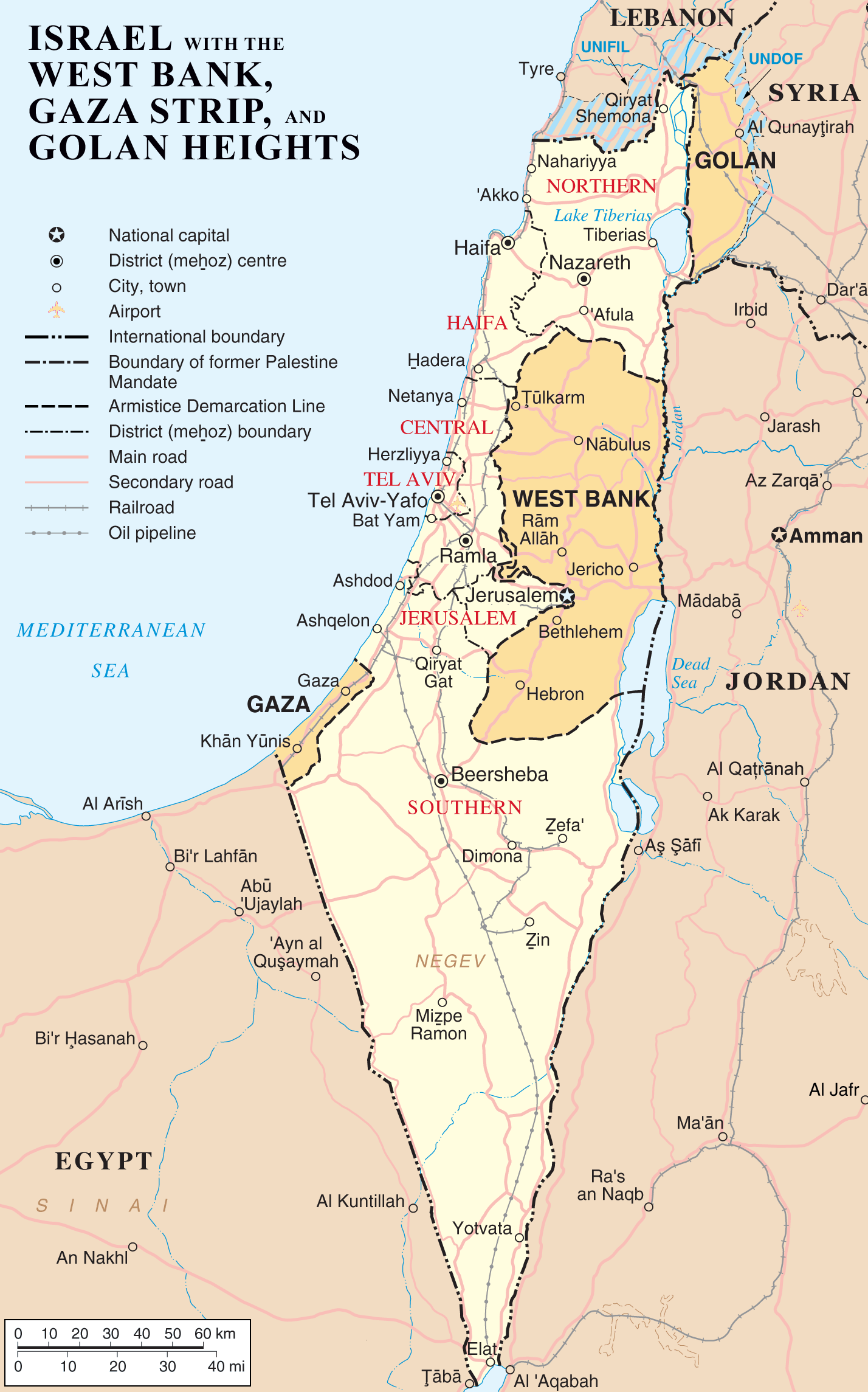

What happened next? In 1967 Israel captured the rest of the former British Mandate of Palestine, taking the West Bank from Jordan and the Gaza Strip from Egypt.

In 1973 Syria tried but failed to regain the Golan heights and Egyptian military forces invaded with some success.

Following the case fire, Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt and Egypt became the first Arab country to recognize Israel.

Israel annexed East Jerusalem in 1980.

In 1987, a new Palestinian uprising began. The following year Chairman of the PLO Yasser Arafat declared Palestine’s independence.

In 1993, Israel and the PLO agreed to the creation of a Palestinian National Authority (PNA) as the interim self-government body to administer 39% of the West Bank under the PNA’s Fatah faction and the Gaza Strip under its Hamas wing. Further negotiations were to take place but did not.

Israel continued to occupy 61% of the West Bank.

In 2000, another uprising began. That came to an end following the death of Yasser Arafat and Israel’s withdrawal from the Gaza strip. Israel retained control of the Gaza Strip air space and coast.

In 2011, the President of the Palestinian Authority and Chairman of the PLO submitted Palestine’s application for membership in the UN.

In 2012, the UN granted de facto recognition of the sovereign state of Palestine. Canada, Israel and the USA voted against the upgrade. President Obama said “genuine peace can only be realised between Israelis and Palestinians themselves … it is Israelis and Palestinians – not us – who must reach an agreement on the issues that divide them.”

The State of Palestine can now join treaties and specialized UN agencies, pursue legal rights over its territorial waters and air space, and bring “crimes against humanity” and war-crimes charges to the International Criminal Court.

What may be the future for Palestinians, and what is indicated for our foreign policy?

A state with the territory of Mandatory Palestine could have become self-supporting. One made up of the land-locked West Bank and the separate Gaza Strip can not.

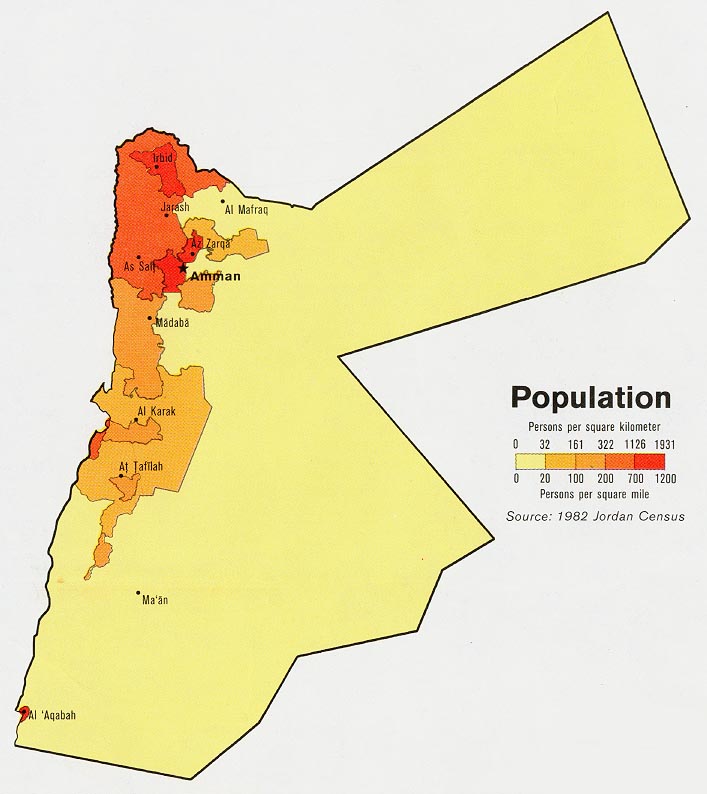

Jordan’s first king may have been right–a state whose territory included the West Bank as well as today’s Jordan could have been good for Palestinians.

A non-viable but internationally recognized State of Palestine may be a necessary stepping stone for Palestinians and Israelis to make peace but a different arrangement of territories in that region is inevitable.

History shows the absurdity of our belief that the borders of existing nation states just need to be accepted and democratic elections established, then all will be well. Borders make administration possible. Believing people on the other side of the border are intrinsically different breeds fear and makes peace impossible.

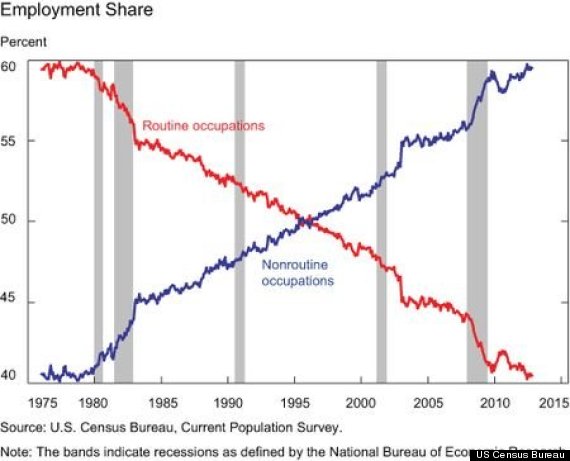

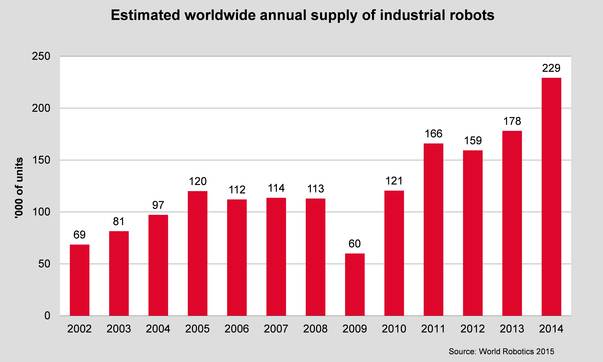

What has already happened is jobs previously done in America went where wages are lower. What is happening at an increasing rate now is jobs done by humans are going to machines.

What has already happened is jobs previously done in America went where wages are lower. What is happening at an increasing rate now is jobs done by humans are going to machines.

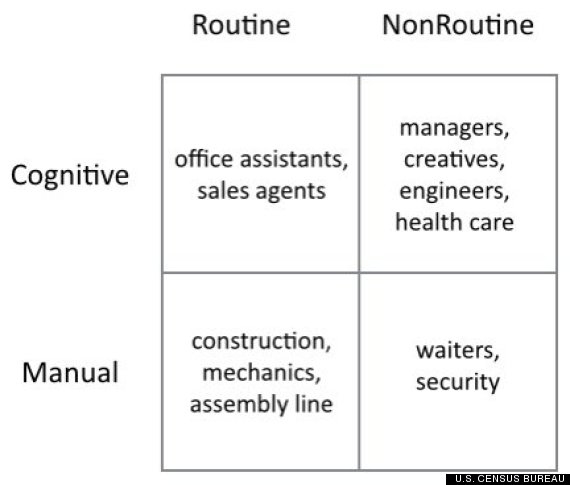

Researchers employing the quadrant chart tool

Researchers employing the quadrant chart tool