Wars used to be fought for control of land, resources and people. Some went on a long time, but they all ended. Now, however, war is for the USA an industry. Its goal is not peace and stability, but ever-growing war and instability.

Media bloviating about protecting the homeland, supporting allies, and spreading democracy is a well functioning distraction. Industry leaders are expected to deliver growth, so warfare industry leaders are promoting terror.

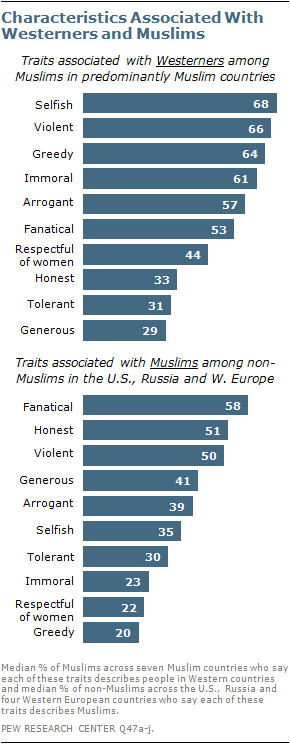

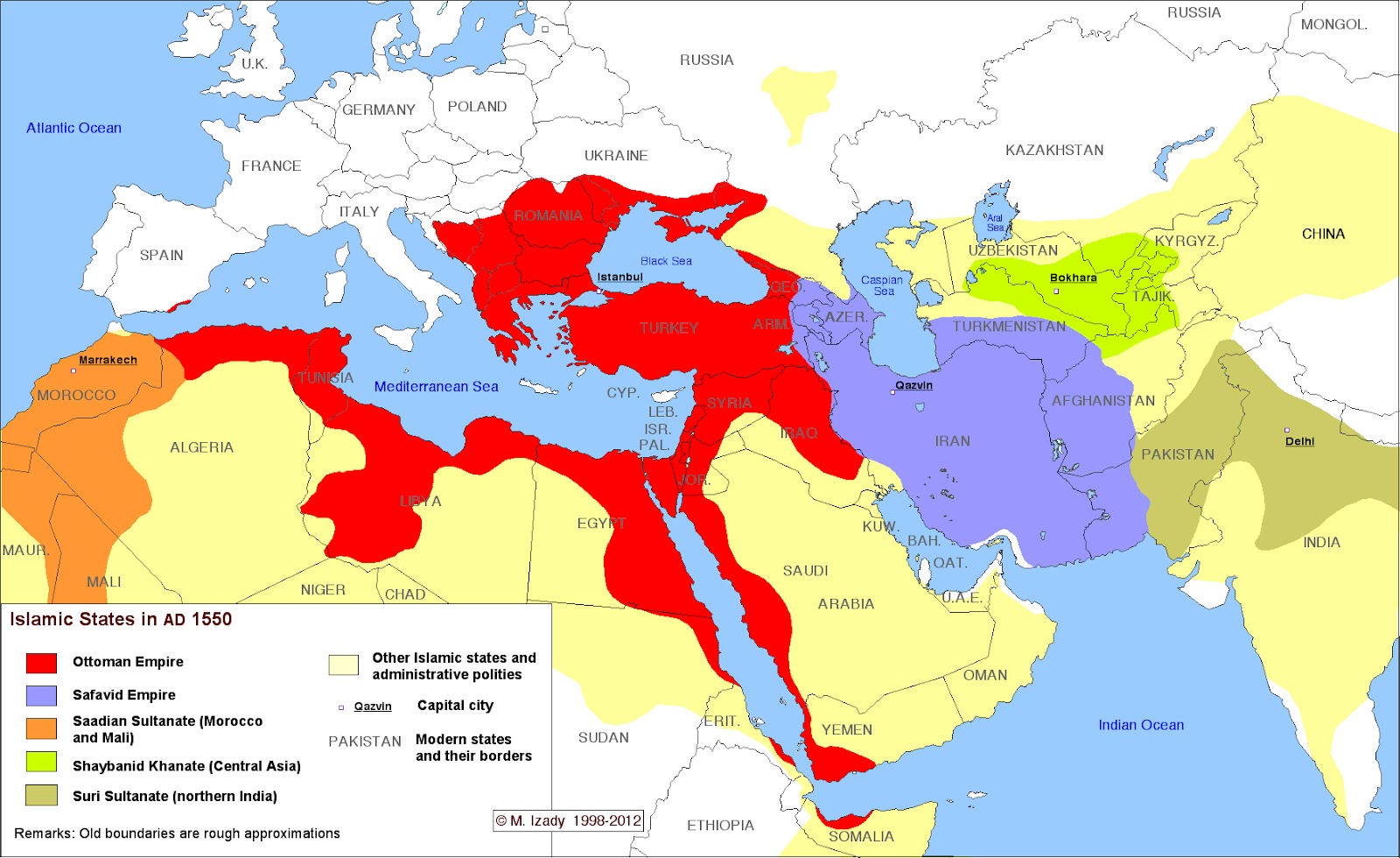

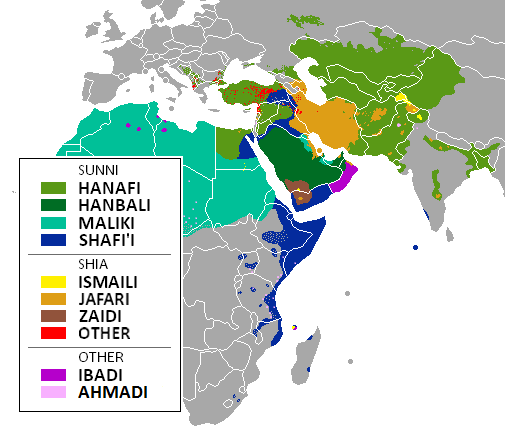

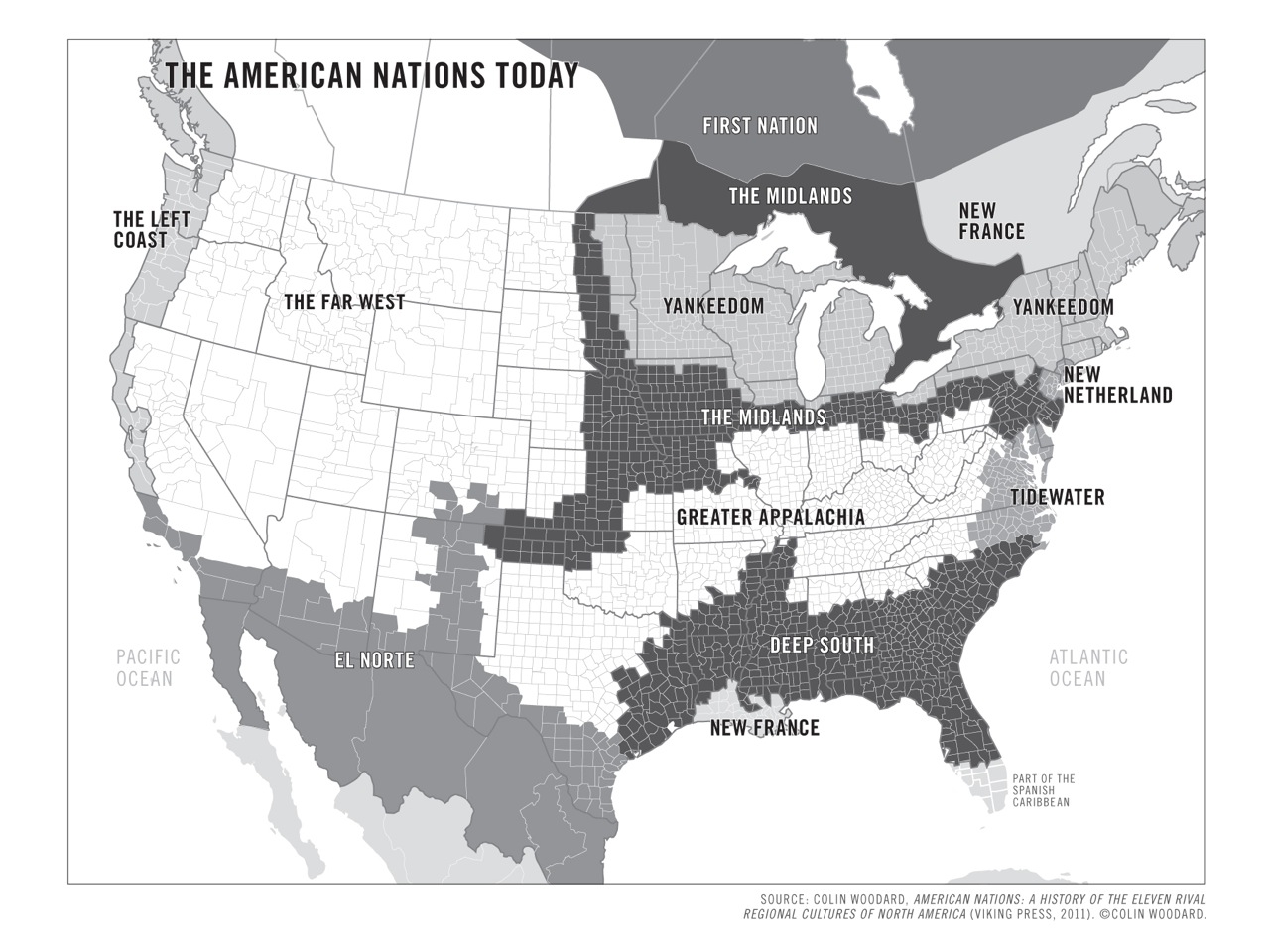

Over the past decade the Middle East warfare market has been well penetrated to become a base for expansion throughout the area encircled by the “Functioning Core”:

![Air_and_Space_MajGenMcDew [Compatibility Mode]](http://martinsidwell.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Air_and_Space_MajGenMcDew-Compatibility-Mode.jpg)

The GlobalFirePower project, which tracks defense spending around the world and shows our spending ($577B) to be four times higher than our closest competitor, China, and almost ten times higher than our former arch-rival, Russia, headlines its website: “Going to war is never a decision to be taken lightly, especially when considering the overall cost of such ventures.”

So how did it happen that we no longer consider the cost of wars, and why is it that we no longer decide whether to undertake them, only where we will make wars?

As these Federal Budget charts illustrate, we categorize military spending ($598B) as “discretionary” unlike Social Security and Medicare which are funded via dedicated taxes. Discretionary means not mandatory, but no politician proposing big cuts in military spending is electable.

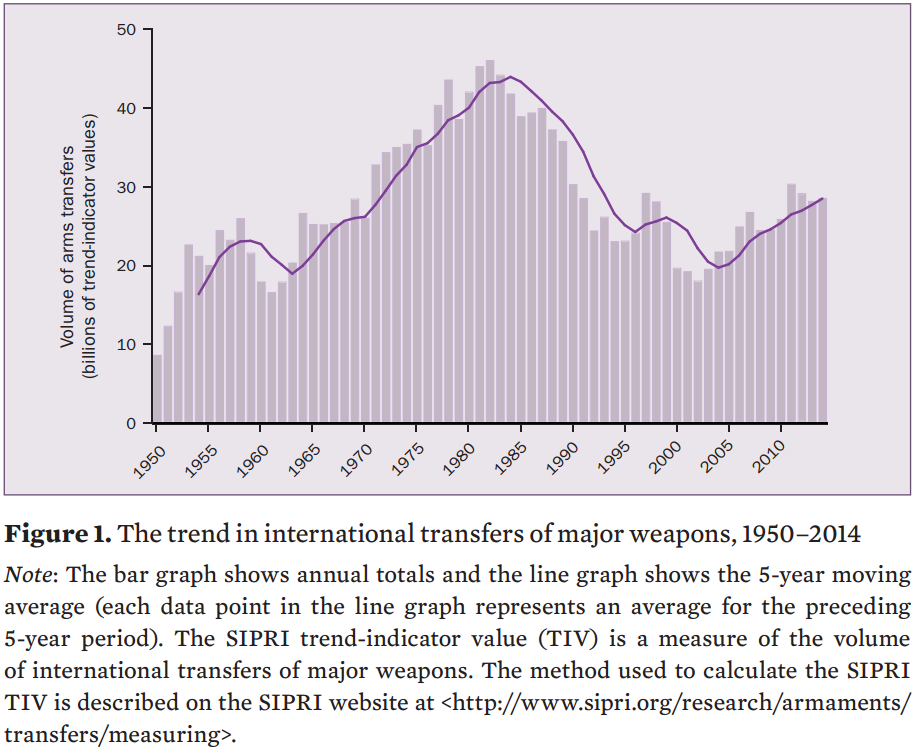

I’ve written before about Our Sacrosanct Jobs Program (“One man spoke of the mass unemployment of the 1930s and said that if we could attain full employment by killing Germans, we could have full employment by building houses, schools and hospitals”) and I’ve written about our arms export industry whose collapsing market after the Cold War was rejuvenated by President Bush’s War on Terror.

It was only in President Eisenhower’s 1961 Farewell Address, when he would never again seek election, that he warned:

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

Two years later, in 1963, President Kennedy tried again. Condemning the demonization of Soviet leaders, he warned against the Pax Americana we still seek to enforce today:

“What kind of peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war … I am talking about genuine peace – the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living … let us not be blind to our differences – but let us direct attention to our common interests and to means by which those differences can be resolved.”

President Kennedy was soon assassinated, his successor, President Johnson, led us into the Vietnam nightmare, in the next decades we greatly increased our military spending while fighting only small wars, and then President Bush hoodwinked us into a War on Terror that can by definition never end.

Now, when President Obama endorses spending $1,000B+ over the next three decades to enhance our ability to fight nuclear war using weapons with more flexible targeting and a range of yields even down to that of large conventional weapons, Ike is not among Obama’s potential successors.

Let’s take stock. How is Pax Americana going?

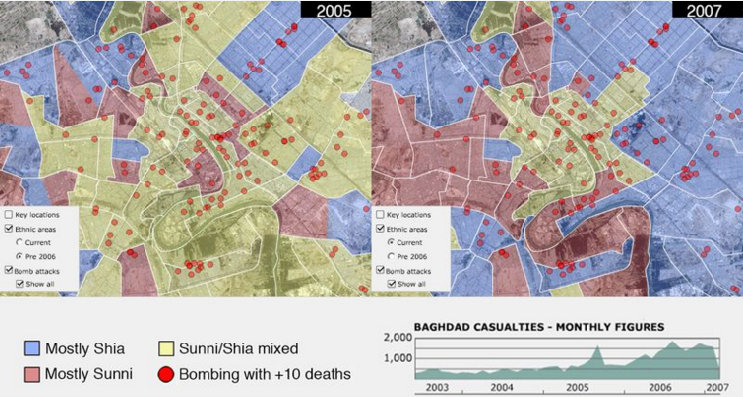

Late last month Iraqi forces retook the provincial capital, Ramadi, from the Islamic State. That was possible primarily due to US airstrikes which, of the city. Victories like that destroy peoples’ means of existence.

“We have come to believe it is not only right but good to send our children to kill, and we revel in the destruction our media presents.”

failing or failed states, we will drop another 23,000 bombs on them and others this year, and our drones will go on creating there, in Pakistan and beyond.

Back when I was a Senior Vice President of a large global enterprise, I sometimes imagined my colleagues’ decisions that would have bad results to be stupid. They were not. I was the stupid one, not recognizing those results were desired. Now, our warfare industry leaders and I want different results.

The War on Terror will continue to grow our market. The state of our warfare industry is strong.