I explored how to prevent more such killings after the school massacre in 2012. Nothing was done then or after subsequent massacres and now we’re horrified again by the massacre in Florida.

Why do politicians text “thoughts and prayers” and do nothing else, and why do we accept that? Because our culture is steeped in violence. School massacres are exciting news but they are a tiny proportion of the everyday killing we pretty much ignore.

Around 30,000 Americans die annually from suicide, homicide and accidents involving firearms. We’re ten times as likely to be killed with a gun as people in other developed nations.

Thirty Americans murder one another every day. We’ve had 270,000 murders since 2000 and police killed over 12,000 people from 2000 to 2014.

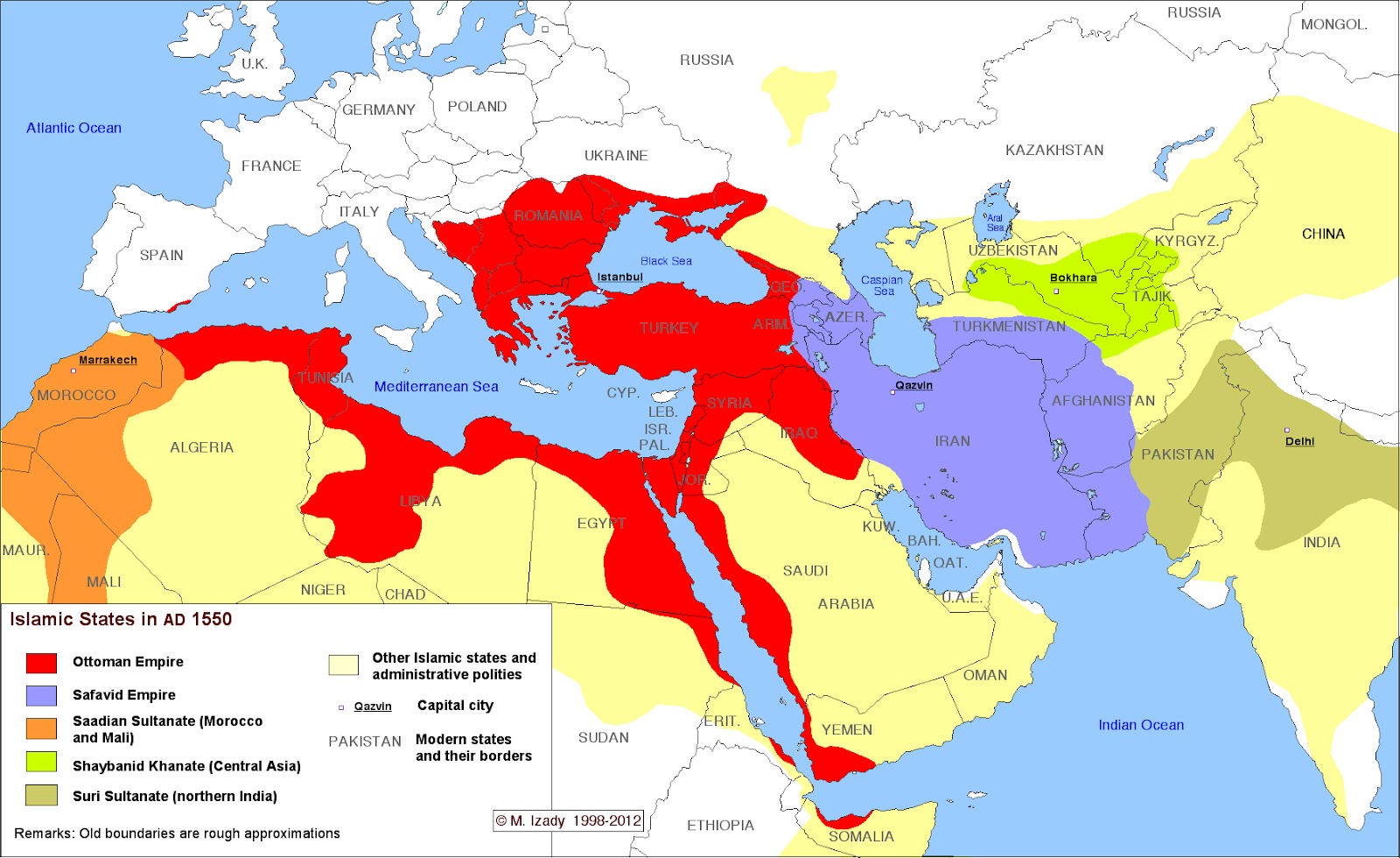

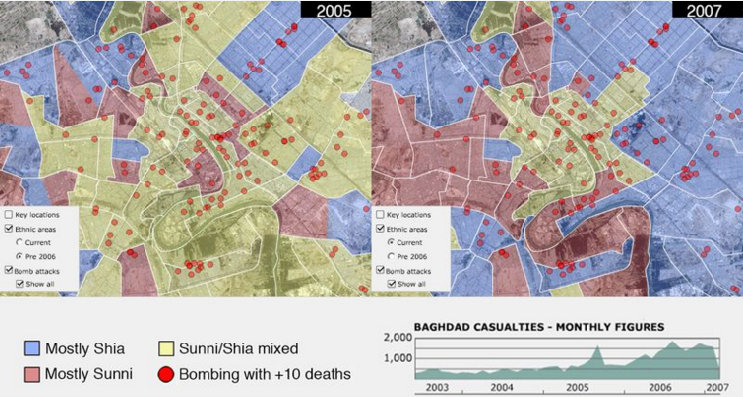

We’ve killed over 20 million people in 37 countries since World War II. Our military forces were directly responsible for 10 to 15 million deaths in the Korean, Vietnam and Iraq Wars. and in wars where we share responsibility there were 9 to 14 million deaths in Afghanistan, Angola, the Congo, East Timor, Guatemala, Indonesia, Pakistan and Sudan. We’re waging war all over the world from almost 800 military bases in over 70 countries and most of us have no idea where or why.

To support and extend all that killing Congress voted nearly unanimously to increase military spending to $700 billion in 2018 and $716 billion the following year. That’s an extra $165 billion over two years, which is more than the entire military budget of any other country except China. The military spending we’re told about consumes 57% of federal discretionary spending. Hundreds of billions more is buried in other budgets. In fact, we spend well over a trillion dollars per year.

We do all this killing because fear and fascination with violence is so deep rooted in our culture.

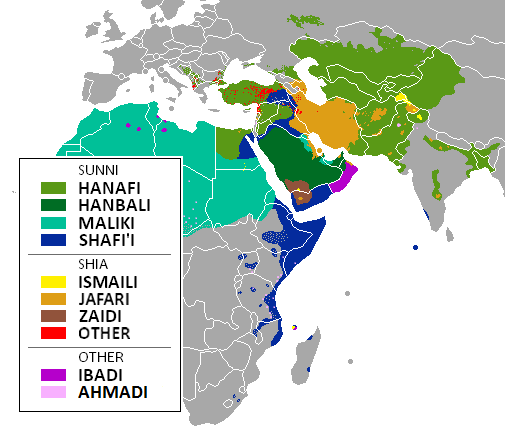

Our ancestors destroyed those who lived here before and they imported and brutalized Africans to do their work. In my lifetime, Russian and Chinese communists were going to destroy us. Since 2001 global terrorism has been the existential threat and now we’re told we must also prepare anew for war with Russia and/or China, which means we must spend over a trillion dollars on new nukes.

Much of what we’re told to fear is nonsense. Domestic right-wing extremists, for example, killed three times as many Americans as Islamist terrorists did between 2001 and 2015. We’re twice as likely to be shot by a toddler as by a terrorist. North Korea’s leaders have a perfectly sensible reason for wanting nuclear weapons – the threat from us. And so on.

Meanwhile, real causes for concern are ignored. Shootings of all kinds, accidental by toddler, intentional by alt-right terrorist, or whatever are inevitably commonplace here because we are by far the most heavily armed nation with the loosest gun regulations in the world.

We have 114 million handguns, 110 million rifles, 86 million shotguns and an estimated 1.5 million military-style weapons like the AR-15. The AR-15 used in school and other massacres, the civilian version of the military’s M4, is designed to obliterate human flesh. As Florida Sen. Bill Nelson recently stated: “I’ve hunted all my life … but an AR-15 is not for hunting. It’s for killing.”

Why do we need guns for killing? We’re told it’s to protect ourselves. In fact, the 2nd Amendment was so we could defend our country without a standing army. Our Founders said we should not have a standing army because if we did, we’d always be at war . We’ve proved them right. The idea that the 2nd Amendment protects an individual’s right to bear arms not just so they can be ready to support a state-sponsored militia dates only from a 5-4 Supreme Court ruling in 2008.

We’re fascinated by violence. Our heroes have always been militarized. First it was Minutemen. It was Wild West gunslingers when I was a boy. Now it’s Special Ops. The lone killer who defends what’s right is a powerful national myth.

We support but don’t think about the destruction and killing we do overseas. We don’t think very much at all, in fact, mostly just believe nightmares fed to us. The roots of our insecurity are old and very strong. From them grows our fear and that from that comes our sense of entitlement to wreak violence.

It will take many, many years to transcend that legacy and we will do it only by taking step after step away from what we now consider normal. Here’s a step we took. More than 4,000 black Americans were lynched between the Civil War and World War II. Then Billie Holliday and others made us stop accepting that viciousness. She made us wake up and feel.

I’m hoping we’re being woken up now by our children so we will take a new step. I’m hoping the time will soon come when we will ban assault weapons and make other changes to end school massacres.